Dr. Larry Arnn on Churchill on technology and modern life

I recently finished Hillsdale College’s course on Churchill, hosted by the school’s president, Dr. Larry Arnn. If you don’t know, the school is as conservative as schools get. Arnn is also on the board of the Heritage Foundation, also as conservative as they come. Both institutions support policies and activities that pollute and deplete.

To my mind, activities that pollute and deplete deprive people of life, liberty, and property without due process of law and violate the principle of the consent of the governed—that is, they violate the US Constitution and Declaration of Independence. People at those institutions haven’t seen that problem yet, as far as I can tell, but it looks like they violate their values.

A different, though similar, violation appeared to Churchill. As he lived through the development of machine guns through hydrogen bombs, and played a role in the development of the atomic bomb, he saw how science could destroy everything. He wrote that each side in a modern war faces “the loss of everything that it has ever known of.” If we only develop but don’t think and apply our values, we won’t like what happens.

Churchill was considering science and technology in war, which kills and destroys, but it seems to me that what he wrote applies to activities that pollute and deplete, which kill and destroy.

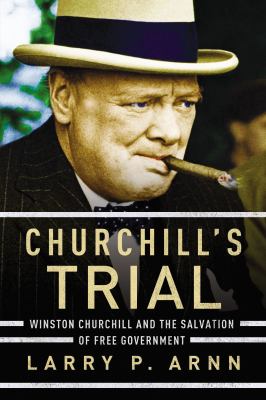

Here is a passage from Arnn’s book Churchill’s Trial. I propose reading it, substituting for “war” words like “pollution and depletion.” I think Churchill’s views apply. Recall, nobody chooses war for the sake of war. We choose war to protect ourselves and our values in the way we hope minimizes killing and destruction.

Likewise, nobody chooses to pollute and deplete just to pollute and deplete. We do it to protect ourselves and our values.

Try reading the following with that substitution and see if you don’t see a conservative approach to ending pollution and depletion. Naturally, if you haven’t tried it, a lack of hands-on practical experience will fill you with defensive thoughts of the Stone Age and Russia or China invading, but try holding back from solutions before understanding the problem.

Churchill stated the problems posed by modern war most fully in a 1924 essay entitled “Shall We All Commit Suicide?” He began, “The story of the human race is War. Except for brief and precarious interludes, there has never been peace in the world; and before history began, murderous strife was universal and unending.” From his propensity to slaughter, man has been saved so far only by his incompetence: “The means of destruction at the disposal of man have not kept pace with his ferocity. Reciprocal extermination was impossible in the Stone Age. One cannot do much with a clumsy club.”

But then, Churchill continued, war becomes a collective enterprise. Roads are cut. Armies are organized. Improvements “in the apparatus of slaughter are devised.” Animals are harnessed to the destruction. Yet still man is not able to do the worst because his governments are not “sufficiently secure.” His armies are “liable to violent internal disagreements.” It is difficult “to feed large numbers of men once they were concentrated, and consequently the efficiency of the efforts at destruction became fitful and was tremendously hampered by defective organization.” This made “a balance on the credit side of life.”

Only in the twentieth century has man gained the competence to destroy himself. Now man is organized into great states and empires. Science and organization bring prosperity, a blessing to man, but the factors of production are also factors of destruction. And democratic institutions give “expression to the will-power of millions.” Education, the press, and religion supply their encouragements. Above all, “Science unfolded her treasures and her secrets to the desperate demands of men, and placed in their hands agencies and apparatus almost decisive in their character.” Churchill summarized the point in one of the most dismal passages he ever wrote:

Mankind has never been in this position before. Without having improved appreciably in virtue or enjoying wiser guidance, it has got into its hands for the first time the tools by which it can unfailingly accomplish its own extermination. That is the point in human destinies to which all the glories and toils of men have at last led them. They would do well to pause and ponder upon their new responsibilities. Death stands at attention, obedient, expectant, ready to serve, ready to shear away the peoples en masse; ready, if called on, to pulverize, without hope of repair, what is left of civilization. He awaits only the word of command. He awaits it from a frail, bewildered being, long his victim, now—for one occasion only—his Master.

Progress, then, presents a logical problem. This is the lesson of Omdurman and later of the Great War. Men are still what they were: their virtue is not improved, and their guidance is not wiser. And yet they have accumulated such powers that a single use of them can pulverize civilization. This new power, afforded by scientific progress, draws upon the very virtues of men to make them more dangerous to themselves. The tools of science, of good organization, of the unprecedented ability to involve the opinions and interests of millions into the making of state policy, take man to a place he has never been before. And now these new capacities turn their attention upon man himself. This is the cause of the new peril of war, a cause that can overcome everything. Science has, Churchill wrote in 1931, “laid hold of us, conscripted us into its regiments and batteries, set us to work upon its highways and in its arsenals; rewarded us for our services, healed us when we were wounded, trained us when we were young, pensioned us when we were worn out. None of the generations of men before the last two or three were ever gripped for good or ill and handled like this.” In this essay, entitled “Fifty Years Hence,” Churchill predicted many things that have come to be: the nuclear age, advances in microbiology, and telecommunications. These are all fact, and greater things still are coming to be.

Science is necessary, and also science is a master. As the human ability to make grows, the human ability to control the engines by which we make diminishes. The logical problem is relentless: we may stay as we are and lead shorter lives of pain and trouble, or we may use our capacity to make our lives easier and safer. If we do that we will gain power, and we can use that power against ourselves.

Churchill raised the hope that science itself will lead to the amelioration of these dangers but was quick to discard this hope: “[T]he hideousness of the Explosive era will continue; and to it will surely be added the gruesome complications of Poison and of Pestilence scientifically applied.” Mankind is progressing toward destruction. Only an improvement in certain virtues of man—especially the virtue of wisdom or of “wiser guidance”— stands in the way of his elimination.

This perception of the terror of war deepens and extends throughout Churchill’s life. It comes to its culmination with two changes that erupt into the world after the Great War and during World War II. The first is the emergence of totalitarian states, a new kind of politics that exacerbates to extremism certain tendencies that Churchill believed latent in modern society. They were latent even in the constitutional democracies, even in Britain, although those societies, including Britain, were blessed with powerful safeguards against their extremism.

The second is the invention of atomic weapons. Churchill had known for decades that they were possible. He was heavily involved in the development of those weapons, and he did not regret the action. He was as much as anyone the inventor of the idea of nuclear deterrence, and he was determined that the few nations that possessed the bomb should keep it to themselves for purposes of deterrence. Yet he regarded the development of these weapons as potentially calamitous for mankind.

Nuclear weapons were the subject of his last major speech in the House of Commons, which he gave on March 1, 1955, shortly after the announcement of the hydrogen bomb by the United States. The hydrogen bomb was much more powerful than the atomic weapons used against Japan, and Churchill thought the change in power important, a difference in degree that amounted to a difference in kind. It revolutionized “the entire foundation of human affairs” and placed mankind “in a situation both measureless and laden with doom.” He continued: “Major war of the future will differ, therefore, from anything we have known in the past in this one significant respect, that each side, at the outset, will suffer what it dreads the most, the loss of everything that it has ever known of.”

No advocate of the nuclear freeze or of unilateral nuclear disarmament ever spoke more dreadfully about the prospects of nuclear war. The terror presented by this kind of war amounts to a change in the moral situation of men.

Here then is the new situation: men can now build societies in which large populations can enjoy security, comfort, freedom, and plenty. The tools that enable them to build such societies, unknown in the ancient world, can also be used to destroy those societies. This changes the relationship between construction and destruction, between building and tearing down, between saving for the future and living for the present. It is in principle a demoralizing fact if by morals we mean the virtues that lead to peace, harmony, and plenty in a modern society.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees