084: Geoffrey West, part 1: Simplicity beneath it all (transcript)

Our environmental behavior as a species and growth as a species is more predictable than you’d think. This recording is longer than most because Geoffrey West is an accomplished physicist and has moved into biology and other sciences. He’s written popular stuff so it’s accessible material. I find that what Geoffrey talks about aesthetically beautiful in that it combines biology, sociology, cities, math and beyond individual fields it takes data from all over the world and he ties it all together with a physicist’s perspective. As you know I have a PhD in physics so that perspective is very interesting to me but more important relevant to our times. Nonetheless he describes it simply and therefore accessible to the layperson. His research critically applies to a modern situation with data coming from all over the world. As best I can tell it is distinct from the usual measurements for global warming and other types of environmental things so it’s not subject to the same systematic biases. In about an hour through you’ll find his academic research led to the same conclusions that my life research did. The importance of leadership. Interestingly, he was similarly influenced by Donald Trump. At the end when everything ties together you’ll hear why I find it so incredibly rewarding and motivational for me and I hope you to lead and not just hope for the best from existing systems.

***

Joshua: This is Joshua Spodek. This is the Leadership and the Environment podcast. I’m here with Geoffrey West. Geoffrey, how are you?

Geoffrey: I’m fine. Thank you, Joshua. Thanks for having me on.

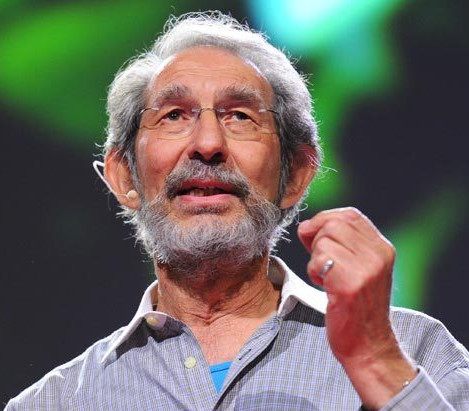

Joshua: Glad to have you here. And I guess now we’ve talked a whole bunch of times. I guess I probably heard of you before but I first heard you speaking on the Sam Harris podcast. You began as a theoretical physicist trained in Cambridge, went to Stanford. You are at the Santa Fe Institute where you’re professor, former president. Now people are thinking, “Oh, this is going to be kind of heady stuff†but you’ve also written a book on a lot of your work that you’ve taken the physicist perspective and applied it in lots of other areas, in particular nature and animals, biology, cities and you’ve talked with TED, I think you’ve been on Nova. So to anyone listening, first, I believe this is going to be a great conversation and if you look him up and watch his stuff and read his things, it’s very accessible. So even though you’ve had all this training, you make your writing and your speaking very accessible.

Geoffrey: Thank you.

Joshua: Your book is about a year old now, maybe you can mention…

Geoffrey: The book came out about a year ago. It’s now a paperback. And what can I say? It summarizes a lot of work I’ve been involved in since joining the Santa Fe Institute and turning my attention away from what I spent most of my career during which was high energy physics meaning [unintelligible] and gluons, fundamental laws of nature, dark matter and so on, evolution of universe so these marvelous questions.

Joshua: That’s what got me into physics.

Geoffrey: Yeah, I know it’s wonderful, it’s wonderful stuff. You know I’ve been asking big questions about the basic constituents of matter and the fundamental laws and going in a certain sense to the complete other end of the spectrum dealing with, how shall I put it, sort of the messiness that is on the surface of this planet you know mostly life and trying to understand within the same paradigmatic respective of the lens of physics sort of much of the world around us, everything from how life works, how it scales in particular, that was the technical lens I used, the idea of scaling which maybe we can talk about shortly but things got life from the microscopic all the way to the macroscopic and clearly ecosystems. But then into something that I began to realize it was more important and even profound and that is to understand social organizations, in particular cities and as a [unintelligible] companies but in particular realizing that the fate of the planet, meaning the fate of human beings and now socio-economic lives are completely intertwined with what happens with our cities because cities have begun to dominate the planet in the last couple of hundred years.

Let me just give a couple of statistics. We’ve gone from being for example in the United States two hundred years ago we were just a few percent urbanized which is typical of now developed countries but now typical of the developed countries such as the US is that we are over 80 percent urbanized. Most of us live in urban environments, the globe as a whole past the halfway point where more than 50 percent of people are urbanized just a few years ago and is headed towards the 70-80 percent level. And all of the problem, here is really important point – not just that all the people are living in cities but building most cities is really going to put huge stress and strain on resources and imaging. But all of the problems that we face, the tsunami and problems that we face from climate change and structure of the environment including pollution and so on but also questions of health, crime, questions of stability of markets, how do we understand risk, what is the long-term sustainability of the planet. All have their origins in the growth of cities, a phenomenon of urbanization and how that’s going to play itself out.

So that I didn’t realize frankly when I started to get into this but as I did I began to realize the enormity of the question, drop me passionately involved not just in understanding cities but using it as a platform to stop to ask about this deep question of long-term sustainability of the planet itself in terms of our role on the planet.

Joshua: Now I want to get a little more detail on the scaling things that you talked about and I want to frame things what you just talked about and I think what you’re going to talk about as this is a view that physicists have, I mean scientists in general, but I think the physicist’s perspective brings something new that I think is incredibly valuable. I mean I have a physics background. Historically, there’s a few physicists who have left physics or done things outside. I think of [unintelligible] is one of the big ones who predicted a lot of properties of DNA long before anyone found DNA and then it was Crick, out of Crick and Watson. Richard Feynman did lots of things. And the way I look it in my head is these great physicists left physics and destroyed other fields, I mean in a playful way.

Geoffrey: I’m not sure I’d use that same phraseology but I understand what you mean.

Joshua: I guess in a way that entrepreneurship they talk about creative destruction, it’s kind of that way. They came in and did things that no one else thought that way and then they came in with not simplistic but they saw this simplicity in something and drew something out. And I believe that I’m doing something like that in leadership and possibly in the environment. So you’ve become a role model for me and also everybody listening who is not familiar with physics I think that… I want to frame what they’re going to hear from you now about what you’ve done. I hope that we’ll also apply that… I think it will just transition as we’re talking about the environment and what we do about it.

Geoffrey: Yeah, sure. Absolutely. You know it’s sort of interesting in a way because physics concerns itself with what you might call simple systems I mean that is things that are amenable to analysis. Otherwise we wouldn’t do physics, we’d use the language of mathematics to not just describe them but to understand them in a very deep way and understand the nature of physical reality, so to speak. And it has proven to be extraordinarily powerful and has laid the groundwork for the kind of scientific technological society we live in. I mean what we’re doing now could not take place obviously unless someone who understood the fundamental laws of electromagnetism and Newton’s laws of motion and all the rest because what great achievements science was the absolutely remarkable prediction by James Clerk Maxwell in the middle of the 19th century that by trying to understand electricity and magnetism he predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves. That has revolutionized our lives.

Joshua: At a constant speed no less.

Geoffrey: And to recognize this there’s this huge spectrum of electromagnetic radiation and this is one piece of radio waves and bouncing things off satellites and so on. This is extraordinary. But we could call those kinds of systems simple even though they’re extremely complicated, I mean they’re extremely complicated. But I want to use the word simple and I want to just discuss this briefly as before we sort of get into the meat of this because simple in this context means that we can write down a few equations or even an algorithm and make predictions, understand and make predictions. And that is the nature of physics and that’s a sort of our way of thinking and [unintelligible] that is also the search for generic underlying principles that transcend individual system so that there’s a kind of universality, something that pervades everything like Newton’s laws. Newton’s laws act on us where we walk or where we jump. But it also is the laws that govern the motion of planets around the sun or those very satellites which we’re using now to bounce signals off so we can talk to one another.

Joshua: As well as planets around some star, around some distant galaxy billions of light years away. Yeah.

Geoffrey: Exactly. So these things permeate the entire universe, these laws and that’s why physicists have coined the phrase universal even though sometimes it may be not for the entire universe but it has that sense that it transcends a tremendous range of phenomena which superficially may seem not connected. Now this is very important and this is a way of thinking. Now the world around us, you know if I look out the window and I see these trees and the whole ecosystem out there and I look down on the city of Santa Fe, there’s houses and there’s traffic and there’s people living their lives. It’s very hard to see where there’s any regularity or systematic behavior. We have this image that each city has its own individuality, it is unique and that each organism is unique and that we supported that to some extent by a sort of naive view of natural selection, evolution by natural selection because that says that there’s this kind of evolutionary history where a lot of accidental things happen, a lot of interaction with the environment, with other species and that’s how each species has evolved, by interaction. And what we’ve ended up with is somewhat arbitrary capricious. So the idea that if we started over again, it would look quite different maybe. But there’s this idea that each species is quite special and there’s kind of this random behavior out there and that’s what natural selection is about. Those the survival of the fittest that can deal with that continuously changing environment.

From that viewpoint, it’s very hard to see regularity and in particular if you do the following kind of thought experiment if you made various measurements on organisms you know how much energy they need, how much food they need, what the various aspects of their physiology or their life history meaning you know how long they live, the rate at which they grow, the offspring they have. Anything that you could measure about them and you plotted this on a graph versus the size of the organism meaning very small things are going up very big thing.

Joshua: So that’s not necessarily a natural question to ask.

Geoffrey: No, that’s a physicist’s question to ask. That’s exactly a physicist’s kind of question to ask. How do things change? When you think of some variable or characteristic that you know does change but you see how one depends on the other or ask, “Does one systematically depend upon the other?â€

Joshua: And there’s no reason to suspect one way or the other before measuring?

Geoffrey: No, a priori, no. Absolutely. So in that sense the physics is first and foremost an experimental and observation science and it’s very much data driven. You have that data, you have measurements and it is fundamentally quantitative which means if it’s quantitative, that the natural language to describe things is mathematics, the symbolic language to be quantitative. So if you made this plot of these various characteristics versus size and you have this idea of randomness and natural selection and historical contingency, not just of every organism but every component of an organism, every organ, every cell type, every genome and you plotted that, you would expect to see points sort of randomly all over the piece of graph paper.

Joshua: So actually, to get it more precise. So say we want to look at energy expenditure. You might say elephants use a ton of energy and maybe blue whales on the ocean so maybe they don’t use that much and maybe mice use a lot because they run around so much but maybe slots don’t. And so you wouldn’t expect a pattern.

Geoffrey: Yeah. All of those because they are adapted to their environment. And they’ve had this long history of adaptation to get to where they are. And it’s unique.

Joshua: So random environments you’d expect random…

Geoffrey: You’d expect random behavior sort of that would be the naïve…That’s the extreme naive. So you would expect these points to be sort of…There might be some clustering and sort of but mostly it will be all over the banks. So when you actually want to measure things, you actually look at real data and you find something that’s exactly the opposite that in fact if you make a measurement and that would be very specific. If you measure something called metabolic rate which is technically the amount of energy an organism needs per second to stay alive. That’s roughly speaking. That’s the amount of food it needs to stay alive. So for us that number if you look on your box of muesli or somewhere else or your yogurt, it will tell you it’s almost 2000 calories a day. That’s what we need to stay alive.

Joshua: So the athletes out there know it’s the TDEE, total daily energy expenditure, something like that, in different units.

Geoffrey: So that energy is about 2000 food calories a day and I want to come back to that number in a little bit. That number’s 2000 calories for us and it is different number for different animals. If you plot that versus the size of the animals, if you start say all mammals, let’s start with mammals and you start with a shrew and then you do a mouse and then you do a rat, then you do a cat and a dog and then maybe…

Joshua: A chimpanzee.

Geoffrey: Human being, [unintelligible] giraffe, elephant, adopt the blue whale. So you have this huge spectrum of animals going over a range of signs, by the way, about 100 million. Whale, blue whales, about 100 million times more massive than a shrew and that’s range that we as mammals cover. And when you plot that what you find instead of some random bunch of points on a graph, you find they all line up on a line. All line up in a single line and that line has a very simple mathematical form. And I’m going to say what that is technically I think and then I’m going to try to explain it in English.

So mathematically what we say is is that that line follows something that’s called a parallel and the parallel has an exponent in three quarters. So that’s the word so anyone that’s had some mathematics will understand what I say but probably most of your listeners won’t. So let me try to explain in English what that means or what that implies. So what it means is the following. There are two ways [unintelligible]. First, if you look at two animals of different sizes and you take their ratio of masses what it says is you could determine the metabolic rate of one relative to the other by taking that ratio of masses and during the following Byzantine operation you take that number, you cube it and then you take the square root twice. We’ll get three quarters okay. Pretty weird. It sounds like some medieval alchemical formula but amazingly that would tell you roughly speaking what the metabolic rate of any animal and by extension essentially any organism is on the planet. That’s pretty amazing. So that’s a very weird operation.

Joshua: Yes. It’s not the sort of thing you’d expect, it’s not the sort of thing you’d automatically do. It begs the question of why three quarters. There must be something going on. When you see order, it’s possible it’s just coincidence but it seems unlikely.

Geoffrey: It could be diabolical coincidence.

Joshua: And then what can we predict with that? What’s causing it? What do we predict with it? What else is like this?

Geoffrey: So the first point I want to reemphasize is it’s absolutely remarkable that there’s any regularity. We see this fantastic regularity and it represents some relatively simple and slightly Byzantine sounding operation which is…

Joshua: You said organisms so lizards and birds.

Geoffrey: Within themselves, within their own taxonomic group. So if you take all birds in the same kind of thing it follows the same formula. If you take all fish, same formula. If you take all plants including all…

Joshua: Plants too. Okay.

Geoffrey: Yeah.

Joshua: Mushrooms?

Geoffrey: You go from probably… I don’t know about mushrooms. I don’t know if data has been taken. Probably yes because it’s true of insects, crustaceans, you name it. All have a plain weird formula. So let me explain again another way of stating it and that is that if you double the size of an organism or put it slightly differently if you look at an organism that’s twice the weight of another organism and so there’s twice as many cells roughly speaking, you would naively have expected that the metabolic rate how much energy is needed would be twice as much because there’s as twice as many cells, twice as many customers so to speak.

Joshua: That’s if it was linear but not a parallel.

Geoffrey: And that’s linear, that would be linear and that’s the sort of simple way usually we think about things but in fact what that scaling law with these magic three quarters you know it says it’s no, you don’t need twice as much, you only need 75 percent as much, three quarters as much, roughly speaking. You save 25 percent in the amount of energy or food intake every time you double. So that is whether you double from 2 grams to 4 grams, 20 kilograms to 40 kilograms or 200 kilograms to 400. It doesn’t matter. Every time you double your keep saving.

Joshua: So animals keep getting more and more efficient. [unintelligible] one measure.

Geoffrey: Exactly. Therefore, the bigger the animal, the more efficient. That’s called the economy of scale. So also to put it slightly differently that our cells have to work harder than a horse’s cells because [unintelligible] but our cells are more efficient and have to do less work and need less energy than dogs or cats in a systematic, predictable way in this kind of average sense.

Joshua: So Chihuahuas in Great Danes it is going to be some…

Geoffrey: Yeah. So that’s a whole separate but dogs, dogs and in general domestic animals are a special case.

Joshua: I would guess three quarters somehow we arrive at through some evolutionary process limiting from above and below and then we are and the dogs we are engineering in some different way that’s not following the same process.

Geoffrey: Dog has evolved by natural selection…

Joshua: …before we started breeding.

Geoffrey: The breeding of dogs. We’ve genetically manipulated not by natural selection so that. Even though dog may have it but I’m going to come to this in a minute as to the origin of the scaling laws they may have evolved to be efficient and therefore in some sense optimal when you bred small dogs or big dogs you violated that because you breed a dog to run extremely fast like a greyhound but that dog has to give up something to do bad and most likely it gives up its lifespan. That’s Newton’s law. Or your breed your dog to cuddle up to you in the armchair or a very tiny dog and it also is going to give up so you you’ve allocated resources to different things which have not evolved in order to optimize by some process analogous to the survival of the fittest. And that’s true of all domestic animals and in fact the dog once considered the proto dog…

Joshua: The average dog?

Geoffrey: No, the one… It’s actually is the average roughly but the proto dog, the dog from which all modern dogs have evolved if you look at its size and we know it’s roughly speaking its metabolic rate it is what it should be. So the average dog, the average dog size which is maybe the size of the spaniel or something, maybe with not all that hair and not looking quite so cute its metabolic rate is roughly speaking what it should be but not of a Chihuahua and not of a Great Dane. There are all off the scale. They are screwed up.

Joshua: They’re not on some sort of efficient frontier.

Geoffrey: So let me go back though to use that as a point of departure about the origin of these scaling laws. But first I have to say something else. So we just talked about metabolic rate. But here’s what’s extraordinary that if you look at any physiological variable so once I mentioned like heart rate or the length of your aorta, the first tube that comes out of your heart or…

Joshua: The length of the femur.

Geoffrey: The femur, yeah, or the length of some bone. But anything that you can think of that is measurable or a life history of it as I mentioned before lifespan, time to maturity, growth rate and so on all of these, we could…There’s probably a list of 25-30 of these things, maybe more, aa follow the same kind of systematic behavior with this one quarter permeating through all of that.

Joshua: Did you find this yourself or some of this lingering around before you?

Geoffrey: No, no. So I got extremely interested in this problem back in the 90s because I had become very interested in all kinds of morbid reasons and mortality. I was very interested in death. I’ve always been interested in death and mortality, why we die and why we age. And at that time, I was very conscious of my own aging. I was in my 50s and you know it just so happens I come from a family of short-lived males. I was already I think when I started thinking about this maybe in my mid-50s and my male antecedents usually die by the time before 60s, or my father died at 61, his father 57, my uncles died in their 50s. So all from different things by the way which is kind of weird but we’re sort of a crappy design I guess in some way, we have these fatal flaws. So I sort of assumed that naturally obviously that maybe I only had five to 10 years to live and I became kind of intrigued by what was the process, what are the processes that have been going on in me that meant that I couldn’t do the same kind of things I could do physically, especially when I was 25 meaning, I was 55 etc. etc. Why was I meaning to go grey and so on. All the usual aspects of… My face was beginning to line.

And in so doing I came across this body of work that had been developed by biologists in the early middle part of the century, especially from the 1930s through to the 1950s and it had become you know a very significant area of biology and goes under the name of [unintelligible], that’s its name. It’s scaling. It’s the kind of things we just talked about. How do the characteristics and traits of organisms change with science? That’s called a [unintelligible], a coined term by Julian Huxley. And as I say it began in the 30s and the scaling law for the metabolic rate that we discussed a few minutes ago was first enunciated and discovered in the data by a man named Max Kleiber who was a biologist at what is now called the University of California, Davis, it was agricultural school at that time and he discovered this and since then a great deal of work has been done and it elucidated many of these laws.

And fortunately for me in the early 80s…So there was this stuff that many people and many very distinguished biologists had wondered about, pondered about that there was no theory. But then in the late 40s-50s we had the Molecular revolution in biology but the discovery of DNA and then the whole paradigm shifted. It shifted from the emphasis being on organismic biology to saying everything is now derivable from molecules and in particular from genes. And that paradigm still exists of course, it permeates biology now but it wiped out this deep interest in this bigger picture kinds…

Joshua: And so we’re sitting there waiting for you.

Geoffrey: But in a general thinking bigger picture you know thinking more systemically, more holistically about life and biology, reducing it to molecules and by extension to genes. And with the idea implicit that you know if you understand the behavior of complex molecules and in particular the structure of genes and ultimately develop many years later, the 90s and so on if we could really map human genome, we’re finished. We understand everything you know unsterile diseases, we you know rewarded happily ever after. A completely ridiculous idea by the way.

Joshua: There’s…

Geoffrey: Oh, it’s brilliant work. All that stuff is brilliant and wonderful but this implicit idea that that’s all you needed to do which was actually explicit, almost explicitly stated in the Human Genome Project was clearly…

Joshua: It’s missing all the boundary conditions of the exterior world.

Geoffrey: Well, yeah, I mean it’s like you know the fact is what we’re leaving out is the whole concept of what this institute, the Santa Fe Institute is all about and sort of invented as a science that is the science of complex adaptive systems. And one of the fundamental aspects of that is that observation, the critical observation that there are systems and in fact almost all the systems around us that we interact with where the whole is not the sum of its parts. You are not the sum of all your cells or your genes. The city is not the sum of all the people that live in it, all the roads or all of the buildings. It’s much more than it’s saying of itself in it and what we call the emergent property.

Joshua: I think the example that I was thinking of is you can watch individual ants all day and you’ll never predict an anthill coming out of it.

Geoffrey: No, no ant has any idea of what it’s doing, it is building an anthill just as there you are in New York, Joshua, and here I am in Santa Fe, Geoffrey, we’re made of all our cells, none of our cells has any idea of what we’re doing.

Joshua: This system’s perspective is so missing from… OK, I can’t help but comment that is so missing from people looking at the environment but I’m getting ahead of ourselves.

Geoffrey: Exactly. We will come to that and that’s a critical point but it’s missing from this reductionistic paradigm. And I don’t in anyway want to decry all the wonderful work that is done. We have to do, that’s crucial to understanding that the constituent fundamental level. My God, I spent most of my career doing that in the physical world and [unintelligible] gluons and string theory and protons and neutrons and the rest of that stuff is wonderful. It’s critically important but we also need to understand what the whole is doing and what the system is doing and especially it’s become critically important and we are jumping ahead in terms of dealing with the multiple problems that we face in the 21st century on the planet especially concerning ecological surroundings and the environment.

Joshua: I want to see if we can get to that part because you talked about the scaling laws and I want to just let you go.

Geoffrey: Let me just go back a moment to try to say a few words about where they come from, the scaling laws, because I think that’s crucially important when we come to the more societal questions so cities, companies, well, companies we don’t have to deal with, cities and sustainability and the environment. So let me just talk a little bit about that. So we had these incredible scaling laws that seemed to constrain the logical world around us and that dominated by this curious number one quarter, number four. Where the hell do these things come from? How is it that you yourself were surprised when I said they also applied to plants and trees? So is it not remarkable that the theme scaling laws… So for example, we talked about that in the context of metabolic rate but tree trunks scale in the same way as the aortas in our circulatory system.

Joshua: Yes, and now there’s no way you can look at this and not think there’s got to be something I don’t need.

[unintelligible]

Geoffrey: … and very universal driving it. And of course, the other side, it is almost spiritual side where you see that it’s bringing together the unity of nature that all of these things are somehow interconnected and are being similar laws.

Joshua: Yeah. There’s an aesthetic pleasure that comes from this that is at the root of science for me.

Geoffrey: Exactly. And I think so that’s what many of us get our kicks from. Yes. You know nothing more exciting. So the question is what is it? So that where we have these very different evolved designs on plants, trees, human beings, insects and so on they are very different and yet they satisfy the same scaling laws. And what you realize that we are complex adaptive systems made of many cells we have in our bodies roughly 10 trillion cells, 10 to the 14th cells and they have to be sustained, they have to be serviced and roughly speaking kind of efficient democratic fraction, roughly speaking. And the way that problem has been solved by evolution is almost obvious. It has evolved a bunch of networks that distribute energy, resources and information throughout the body to those cells, within cells or their networks themselves that of course do likewise within cells to the various components of cells. And the idea is that these scaling laws are a reflection of the underlying principles that govern the mathematics and physics of these networks and the same works have generic properties.

Joshua: I can’t help but think that these networks are similar to the networks that we have in distributing goods and services throughout our city or throughout to market and suddenly what people and biologists can apply in other areas and it was waiting for a physicist to make that connection. Am I getting it?

Geoffrey: Yes, yes. I think so, yes. So it is that and we will come to that in a minute. So when you think of yourself so viewing it through these lens you see an organism as a bunch of networks that we are cells of course but we are actually a bunch of networks feeding those cells, we’re a bunch of you know we are circulatory system, the respiratory system, a renal system, a neural system even our bones, our network. And all of these are there to support the totality of that, the system, the holistic system which is the organism. So the idea is that it is the universal laws governing network [unintelligible] mathematics they eventually give rise to the scaling laws and in particular from which you can derive the one quarter in general and the three quarters in particular for example for the metabolic rate. And the kind of generic universality of the network of things that are well, the first one is sort of obvious in a way. It has very profound consequences and that is that and I am going to say it for us technically the network has to be space fully meaning it has to go everywhere. The endpoints of the network have to end up feeding all of the cells of your body. Every cell has to be fed by the end of your circulatory system. It has to fed by the capillary, capillary goes blind and blood diffuses from capillary to the cell. So this network has to [unintelligible] itself so that every cell is fed so that’s called space fully.

Another universal principle and that of course you see as independent of the specific design. It’s just a general property. Another one which is a general property is the following that we want to translate the ideas inherent in traditional natural selection. [unintelligible] need natural selection into mathematics in the following way that the implicit continuous feedback mechanisms implied in natural selection, “the survival of the fittest†that those that can take advantage of some optimization of something that has evolved gain something, they gain fitness, fitness being the ability to produce offspring and pass on your genes gets translated in this language and the network language into the idea that these networks are in some sense optimized.

So let me give you a specific example. Let’s go back to our circulatory system. So the idea is the circulatory system that we have, we meaning not just you and me, and not just every human being and not just every human being that’s ever lived but every mammal that has ever existed the one that we all share is the one that minimizes the amount of energy our hearts have to do to pump blood through the circulatory system in order to feed cells by delivering oxygen and other nutrients to them. And the idea is you want to minimize that energy which is the amount of energy needed to stay alive sustain the system so that you can allocate maximal amount of energy to having sex and reproduction and rearing offspring. Darwinian to maximize, Darwinian what’s called Darwinian fitness passing on genes. You want to minimize the amount of energy that you devote to staying alive. You want to in that sense minimize the amount of metabolic energy devoted to that. And so you have to put that into mathematics. So you put that into mathematics that no matter what change you base there’s a network, there’s a kind of idealized network that if you made any significant change to it you’d have to do more work to deliver blood.

So the idea is we want to optimize the network. And it turns out when you do that all these scaling laws come out and you can derive mathematically from those kinds of generic principles governing the network, all of the scaling laws and the origin of the number one quarter, the number four. And let me just say one or two words about that correctly. Number four has actually got two components. It’s actually not four, it’s three plus one. Three coming from space filling because you have to fill a space that’s three dimensional because it’s up down and sideways and the plus one constant something that has to do with the optimization because when you optimize these networks it turns out they have to approximate what’s called a fractal like structure sort of similar structure meaning everybody is familiar with looking at a big tree and realizing that if you cut a little branch out of it, put it aside, it looks like a scaled down version of the original tree and you can do that for any branch. It looks like these…. You know it’s just a scaled version of the tree. That’s called self-similar or fracking.

Joshua: And that’s where the one comes from.

Geoffrey: And that one comes from a magic property of fractals that they add an effective dimension. So it’s the three dimensions of space plus 1 coming from the optimization of giving rise to fractality. So it’s 3 plus 1 which is 4. So if we happen to live in seven dimensions, the number wouldn’t be four, we would be eight.

Joshua: And animals would still be more efficient with size but not quite.

Geoffrey: No. But anyway. So that’s the idea. And all of the scaling laws that we talked about and alluded to drop out from there and there’s much, much more.

***

Joshua: And so now here you are and you have the scaling laws. You know why they come about and I think the next step is you’re going to look at other things and say, “Now I can predict scaling laws for other things with networks in them.â€

Geoffrey: Exactly. So that was exactly the idea. There are two directions. One is that one which we can talk about in a moment. The other is just look at various other aspects of life like growth. Can we understand growth this way and in particular can we understand why it is that we grow quickly when we’re young and then we stop? And it turns out that the network does it for you. Do the calculations. We automatically stop and you can predict growth curves of any organism. So that’s the kind of thing you could do. One of the aspects of the life around us in terms of socio-economic light is that unlike us we believe in open-ended growth, economics and finance and that plays into sustainability. The question is what is the relationship between this open-ended growth which we never see in biology to the bounded growth that we do see in biology in which we all live. That’s our life.

Joshua: A lot of people want to see open-ended growth economics but there have been plenty of societies that don’t exist anymore where it did not grow forever.

Geoffrey: So we’re going to go back to that. But that got me into this thinking exactly what you said. We have this now this conceptual framework based on networks and scaling laws. Where else can we apply it? And the obvious one was to look at cities and then that leads to economic systems and sustainability. So the first thing, first question was look, one of the things that we learn in biology is that despite appearances and whale lives in the ocean and the elephant has a trunk and a giraffe a long neck and we walk on two feet and a mouse scurries around despite our different environmental and ecological histories we’re actually at the 80-90 percent level scale versions of one another. We are in fact in terms of everything you measure about us essentially scaled down versions of a whale. It’s amazing.

Joshua: Humbling as well. We think we’re so special.

Geoffrey: Yes. And we won’t talk about the speciality because we’re obviously now a little bit different.

Joshua: Much less special than we thought.

Geoffrey: Yes. When we were hunter gatherers which is only 10000 years ago we were just like that. We were biological and to emerge from that that’s to segue into understanding community structure, collective behavior and cities. And so one of the first question you ask is despite appearances is New York just a scaled up Los Angeles which is a scaled up Chicago which is a scaled up Cleveland which is a scaled up Santa Fe? You know they have different histories, geographies and cultures. And the only way you can answer that is you have to gather all the data of the various characteristics of cities and plot them as we did for organisms versus their size. Size for city [unintelligible for population. So how does you know length of all the roads, the number of gas stations, the number of patents produce, the number of AIDS cases, the number of restaurants. How do all these change as they change cities from a tiny city like Santa Fe which is less than a hundred thousand people all the way out through…

Joshua: Now the only way you could say this is that it does scale. It must. It’s going to scale differently because they’re not three dimensional. It does seem like networks like space filling because you’ve got to get the ambulances going to everyone. So I guess it scales two plus one.

Geoffrey: That’s what you would naively guess. That’s because you’re forgetting something fundamental about cities. So if cities were just physical, if they were just really a super organism, there were great people and New York was actually a great way in some way. Indeed, they would be primarily two dimensional. So instead of four you would get three. Indeed, you’re completely correct. But a city one of things one begins to realize is one who starts to study cities is that of course when you bring up the word city you immediately do think of its physicality, you think of the skyscrapers of New York, boulevards of Paris and the Eiffel Tower, you think of the buildings and the roads and so on. But that is actually what you quickly discover is actually the least interesting part of the city because the city is the people. There is another network which is much more powerful that is going on. That’s the social network and it is the city and the way of thinking about the city is that the city is this extraordinary machine, the most extraordinary machine we have invented, a sophisticated machine we have invented in order to facilitate human interaction in order…

Joshua: So the dimensionality of human interaction…

Geoffrey: That’s the point.

Joshua: Higher or lower.

Geoffrey: Exactly. That’s the point.

Joshua: Yeah, I guess it’s going to be higher but I don’t know why.

Geoffrey: I am going to tell you. So first before answering that question I want to just tell you how cities scale and then we will come back to that very question. So if you look just at infrastructure, if you just think of the physicality of the city mathematically it’s just like biology and in spirit it does. It expresses an economy of scale. In margin the bigger you are, the less energy you need for a cell. You’re about 25 percent [unintelligible]. In cities you need less infrastructure per capita, less gas stations, you double the size of the city you are only twice as many gas stations. Turns out you only need 85 percent.

Joshua: So one sixth less. So it’s five dimensions.

Geoffrey: Sort of, five or six dimensions. So that’s an interesting question of itself but it does behave in spirit like biology. There’s a systematic saving. So you are in New York is the most efficient city in the United States biggest city…

Joshua: Then Tokyo is going to be yet more efficient.

Geoffrey: You need less infrastructure to do the same sorts of things in New York than you do in Cleveland or Santa Fe. This is a systematic predictable way. And what is even more amazing is that’s true of I said gas stations, it’s true of the roads, true of the electrical lines, gas lines.

Joshua: Subway stations.

Geoffrey: Water lines, whatever you want to look at.

Joshua: If energy per person is all that matters, then we’re going to keep getting bigger and bigger cities. It’s probably not all that matters.

Geoffrey: It could be. I mean you know without any judge, no question about judgment lifestyle collectively for human beings good to be in a collective connected communal environment which we call a city.

Joshua: Now if you say collectively you’re implying or I’m inferring that per person it’s maybe getting more stressful.

Geoffrey: Maybe that’s due to social interaction. So there’s the other side to cities which I worded up a moment ago that’s the socio-economic side and if you ask socio-economic metrics which didn’t exist on this planet until we started forming communities so only a few thousand years ago were things like wages or patents or ideas or…

Joshua: Or how fast you’re running around.

Geoffrey: Pace of life. All these things if you ask how do they scale turns out it’s the only place we really sit basically with some minor exceptions but biology is dominated by economies of scale which we call sublinear scaling by the way because the three quarters is less than one to distinguish it from what we see in cities for the first time which we call super linear scaling which is the bigger you are, instead of the less per capita, the more per capita. The bigger you are, the higher the wages per capita, the more [unintelligible] the people there are on per capita, there are more restaurants per capita, the greater the buzz of the city per capita, the more patterns produced per capita, the more AIDS cases per capita etc. etc.

Joshua: So it’s becoming more efficient but also more stressful or exciting.

Geoffrey: Yes, in the sense that more disease including mental disease per capita increases systematically all to the same degree. What is amazing are all these different metrics which superficially seem to be very different, number of patents connected to a number of AIDS cases, they scale in the same way or scale the same degree 15 percent, you get to 15 percent add additional value added every time you don’t. And what is amazing the scaling laws which I’ve done in terms of United States are true across the globe. They are same in Japan, China, Colombia, Chile, Germany, Portugal, you name it, everywhere the same kind of scaling laws which begs the question where in the hell did these come from. I mean it’s almost as if it about 1790 after the American revolution and the French Revolution that there was all this excitement there was a big congress called in Paris and all the nations of the world got together and people said, “Well, look all these marvelous things that are happening and we’ve got the Industrial revolution is coming. We’re going to have to build all these cities because all these marvelous things are going to be happening is the template for how you’re supposed to build your urban system.â€

Joshua: Actually, it’s funny because you said it that way it makes me think well, if they actually did that, we wouldn’t succeed at that because you can’t get humans to coordinate so effectively. So it must not be that.

Geoffrey: We are terrible at that. You know that’s what’s screwed up much of the things around. It turns out that happened organically, it happened by some natural process in the same way that we had the evolution for all the animals and plants.

Joshua: So it’s like when I walk down the streets in New York or when some real estate developer walks down the street and he says, “You know that building it’s too small now that the other buildings around here are taller†there’s a lot of value in that I’m going to buy that building and put up a high rise they are responding to the same natural pressures.

Geoffrey: Exactly. That is they’ re doing. They are like the ants. They don’t realize what they’re doing is building on this. There is this hidden… You know you walk around the city…

Joshua: Actually, you know in The Fifth Discipline one of the things a book where I learned a lot about my first hand my introduction to systems thinking and it said, “When you feel compelled to do something that’s a sign that you’re in a systemâ€. And so you said it’s invisible but it’s actually we’re acting on these motivations. We’re not consciously aware of it but when someone says you know we should put some solar schools up they’re acting on a compulsion, it’s a system that’s operating on them.

Geoffrey: Yes. It’s like the invisible hand so to speak. And it’s kind of remarkable. And it does happen by some natural process. The question is what is that process? And something I want to talk about briefly.

Joshua: Well, also can we resist that process if it’s taking us to a place we don’t want to go?

Geoffrey: That’s the question but I think we have to end up with in terms of sustainability.

Joshua: And this is what physicists bring to the table.

Geoffrey: I hope so.

Joshua: If these laws are out there and we don’t know about them but they still operate on us, if there’s nothing we can do about it I guess it might not matter at all. But if there is something we can do about it, it might be the most important thing to…

Geoffrey: Exactly. So what is the mechanism that’s producing this? That’s the question. And the idea is the mechanism that is producing these social networks is the dynamics organization and structure of our human social networks and as distinct from biology or the infrastructure of cities which are governed by economies of scale physical networks the human social networks what do they transmit. They’re not transmitting energy, they’re transmitting what we’re doing now – information. And as I just repeat what I said earlier the city is this machine for enhancing and facilitating those because we create places and institutions and mechanisms to have us interact. That’s what we do with all the institutions, all our ways, our jobs and so on have us interacting.

Joshua: So Facebook and Twitter are inevitable consequences of cities getting bigger and bigger.

Geoffrey: Once you have the infrastructure able to do that, once you’ve discovered the infrastructure to do that, you are carrying on the process that began with us 10000 years ago, primitive versions of city which started this whole process and the mechanism that distinguishes these networks from biological networks or infrastructure networks is they have built into them what we are doing now a positive feedback mechanism. That is even though you and I talking, it’s not just you and I talking. You are connected to all kinds of people. You are going to be talking to other people, they are going to be talking to other people but in general there are loops at this, there are feedback loops. Usually you know certainly in my life you know I talk to Joe and he talks to Fred and Fred talks to Ann and Ann talks to Charlotte and then Charlotte talks to me, there is this feedback and we build up ideas and most of those ideas are crap, obviously. All their ideas about you know who’s going to win some football match or where the [unintelligible] Trump something all which sort of dies somewhere. But that process that very process what the city is for does, every once in a while, produce the theory of relativity or quantum mechanics or Google, Or Microsoft, or General Motors. That’s what cities do. And so what cities do are create an environment to enhance social interactions by positive feedback mechanisms which create ideas, innovate and create wealth in order as part of the paradigm to improve the quality and standard of living of the citizens. That’s the paradigm we live in and that is fantastic. It has been extraordinarily successful and has brought us to this marvelous point where we can do what we’re doing now and many other almost miraculous things. And we’d all like that to continue with no unintended consequences.

Joshua: Yeah, because there’s what’s called the opiates and there’s obesity. And there is psychological…

Geoffrey: Sure, we pay very heavy price in many ways. We always pay. You know there’s always been the dark side. One of the things I often say is that the scaling laws in terms of social economic activity is the good, bad and the ugly come along together as a package.

Joshua: The good, the bad and the ugly. That’s our judgment. Nature doesn’t pick.

Geoffrey: No but it is our judgment in terms of what we’re allowed to do that when we’re talking about society because society has built into it ideas of judgement. You know we do have moral codes and ethical codes and I don’t think we should shy away from making judgment that having more AIDS cases is bad or having more crime is bad. I think we should make a judgment. I mean there’s huge gray areas obviously about being judgmental but I’m willing to use good, bad and ugly in this sense that that if you increase the size of a city, you get more patents, you get higher wages but you will also get more crime, you get more disease, you get more environmental damage and more stress that all to the same degree.

Joshua: The big question is can we adjust our social interactions in order to…

Geoffrey: So one second before I went on I would try to answer that. I think that’s the fundamental question because one of the consequences of this super linear behavior as a state from the sublinear behavior is the following. When we were finishing up the discussion of biology and sublinear I brought in that idea, I pointed out that that sub linear behavior leads to bounded growth. You know we stop growing. Everything basically stops growing and that is crucial, that has played a crucial role in the sustainability of life on this planet for two to three billion years. That phenomenon of stability that you spend for many organisms most of its life has spent in a relatively stable state and growth happens relatively quickly. When you come to socio-economic systems driven by super linear scaling it turns out something completely different happens. It’s same mathematics actually. But instead of having bounded growth you have open ended growth. So in one sense that’s great in terms of the theory because you and I have theory based on social networks to predict super linear behavior that we see and that super linear behavior leads to open ended growth which is also what we see not only what we see, we demand meaning you know that is a fundamental of the economic system that we’ve developed since the discovery of entrepreneurship and capitalism with the beginnings of the Industrial revolution 200 years ago.

Joshua: That it rests on perpetual growth.

Geoffrey: The idea that we can have this open-ended growth and so on. Now this theory has built into it, not the theory but the consequences of it had built into it a fatal flaw for the system. That fatal flaw is that the system is destined to collapse in some finite time. That’s called mathematically a finite time singularity and it says within some finite time meaning it could be one year, five years, ten years, a hundred years this system has to collapse. That’s it.

Joshua: For internal reasons, not running out of resources, not because of overheating.

Geoffrey: No. Just they would have to because if you want to use the word resources, it would be that you have to have infinite resources in some finite time. And that’s impossible.

Joshua: Is this related to why organisms die?

Geoffrey: No, it’s not. That’s not related. So that’s the caveat to that statement is that if nothing changes, [unintelligible]. Of course, the way out of this dilemma is that you change something and that change we call innovation. We have to make a major innovation which effectively resets the clock. So you may have…To state something very recent. A major innovation was the discovery of computers, especially laptops. Reset the clock. Everything changed when we did not basically. But then you know 15-20 years later within 15-20 years we discovered IT which now dominates, so that reset the clock. And if we go way back, we discovered iron, then we discovered [unintelligible], then we discovered coal. So each one of these stops as you approach the singularity, you sort of reset the clock and you have new boundary conditions, I used that phrase earlier and we can start over again. So you have this marvelous possibility that if you can innovate, you can continue to grow and you can innovate yourself out of it and continue to growth. That’s basically the big term of economists by extension to politicians and policy makers that’s why we need to keep innovating in order to keep growing and that’s what this mathematics predicts. That’s great. But it has also built into it another fatal flaw.

Joshua: And I think that’s going to be…When you’re talking the wheel and fire and the plow it’s like 10000 years between us and from computer and IT it’s like no time at all.

Geoffrey: Exactly. So that’s the big problem.

Joshua: So delaying this falling apart, this collapse but less and less each time.

Geoffrey: Exactly. We have less and less time. So just to put it in perspective, the fantastic thing about biology and that sublinear scaling is that you have bounded growth and also that the pace of life slows the bigger you are. Elephants live much longer than mice in a systematic predictable way. Everything gets reversed with super linear scaling in socio-economic systems and it’s the other way round that instead of as you get bigger time slows down, time speeds up in a systematic way so that just as you say you have to innovate faster and faster. So I might have taken you know a thousand years ago to make a major paradigm shift might have taken a hundred years to develop. That same thing now takes 10 to 15 years.

Joshua: So Mozart is all over the place because we’re going to come up with a [unintelligible] all over the place now. Can we work on a system though? Can we transcend the system and change our social networks in a way…

Geoffrey: That’s the big issue. So I got very despondent when I sort of elaborate on all of this and I go like oh my God, it seems like you know kind of hopeless situation. I sort of painted myself into a corner that there’s no way out of this. We’re destined. It doesn’t matter how clever we are and how much innovation we do, we’re going to have end up with a situation where we’re going to have the equivalent to an IT revolution every six months which is completely nuts. So something more…

Joshua: Or you hit collapse.

Geoffrey: Or you collapse and that’s what the theory says that is if you don’t do that, you collapse.

Joshua: And the collapse… Maybe you want the collapse…. Maybe you want to have it earlier so the collapse isn’t so bad.

Geoffrey: Well, if you could do it smoothly. So there is the question can you do it in a way that you have soft landing rather than the whole social fabric disintegrates?

Joshua: So we want to either get it to level off and change something so that we just keep it where we are.

Geoffrey: So what I began to realize, what got me into a kind of a cynical mode was that you know if you go back again to the theory and this is speculative but the origin of this is social networks and they’re kind of fixed in a way, they’re not fixed but they’re sort of in our DNA. We are urged to be hunter gatherers with this… The same brain that we had 100000 years ago and much of our social dynamics is still controlled by that brain which was determined by being in small groups of people. And so how do we change that? And then I realized that the idea of major innovations or paradigm shifts, these major event changes that is keeping us buoyant we have begun to identify the idea of innovation with a technological change. You know that has always become synonymous. When we think of the word innovation we typically think of some major technological change, anything from the discovery of coal and steam engine to I.T. or on a much lower level you know the invention of an iPhone or an iPad. And then I began to realize that maybe what this is implying that is in order to make a truly major change to get out of this inevitability is that we have to think of innovation not as a technological change but as a cultural change, as a major cultural change in the way we behave. That’s why I was very intrigued by your own decision and the kind of life you are trying to lead which is to disconnect to some extent from the multiple infrastructures that we have around us that are marvelous, they are part of this speeding up and whose unintended consequences and the [unintelligible] therefore its pollution are immense and are part of this thing that’s going to kill us if we don’t do something about it.

Joshua: And to be specific you talk about how my not flying, my avoiding packaged food…

Geoffrey: Exactly. Picking up trash, whatever. But you know these are small and I don’t want to belittle what you do but it’s highly symbolic on an individual and extraordinarily important if we could do that at a collective level.

Joshua: So the Slow Food Movement.

Geoffrey: Yeah. These kinds of things. So we need some major shift, some extraordinary shift and I started to get and I thought about that and I thought well, all well and good but you know for that to happen this is probably going to take 20, 30, 50 years to get a whole society to change because at the moment you know if you ask where a lot of this come from in terms of our social interactions, a lot of it is the idea that all of us want more. We want sexier bigger things and we want more of everything. People might have one car but they want two cars, three cars. They not only want a home but they want a second home. You know we all want that and we all have that in us and that’s part of the driving force that’s got us where we are. But it also has these horrible consequences. So the question is can we get out of this, a better word for greed, kind of driving force.

Joshua: I would say craving.

Geoffrey: Craving. And I felt well, maybe we can but it might take 50 or 100 years and that’s too long.

Joshua: That’s where from an earlier conversation the seatbelts, the drinking and driving.

Geoffrey: Exactly. And so the examples I had that I thought about were indeed you know in my own lifetime the major changes that I thought would never happen are the use of seat belts and people not smoking. You know I grew up smoking. I started smoking at 14, a pack and a half a day. It’s amazing I’m still alive. But I did stop at 21 fortunately. But you know everybody smoked. You know you’d walk into a room into my office and you would be walking into a gloom.

Joshua: To which I had a drinking driving in that early conversation and then I was trying to memorize, I spoke about this because there’s another one which is unleaded gasoline, another big shift.

Geoffrey: Yes, another big one that it was poopooed when it came out. All these things do so but they do take a long time. And these are small I mean they are very significant but small on the grand scale because we need a grand change you know something deep changing. And I thought that was impossible but then I had a tiny glimmer of hope. And it’s bizarre. And that glimmer of hope is Mr. Trump of all people. And it’s extraordinary because Mr. Trump has done something that I thought would be and many of us thought would certainly be impossible. He has got, he let loose, let’s put it that way, that part of us, our sophisticated selves that still doesn’t want to believe in science, doesn’t really want to believe in facts, doesn’t want to believe in rational thought. [unintelligible] made things up as you go along.

Joshua: I don’t want to lose anyone here. Can we say that values other things over those things? That they are looking at patriotism that isn’t…

Geoffrey: I don’t deny… You know I can be quite as irrational as the next person, that’s for sure. It happens that I earn my living and enjoy my life as a highly rational human being but I recognize inside me there are all these other forces at work and I think that’s true for most of us.

Joshua: I think that Trump voters aren’t saying, “Let’s be irrational.†I think they’re saying, “Let’s be patriotic†or something.

Geoffrey: Well, of course, they don’t say that but their actions belie those words in many ways because I think that Mr. Trump feels that he can make things up as he goes along, tell lies or maybe he doesn’t see them as lies because he does make them up to suit whatever the argument is. It’s considered OK. And I naively thought that one of the great aspects of civilization, of modern civilization meaning over the last 10000 years and you know whether it’s you know we live in an area of native American tribes, they too of course had all this land laws and codes and they had a way of dealing with problems and they believed in something they felt was truth. And you suffer consequences when you disobey those. That’s the rule of law. That’s a fantastic invention. And somehow, we’ve been able to skip through, somehow we’ve…

Joshua: For a couple of years.

Geoffrey: In less than a year. In one year when he started running he was president and it happened. And this is my point. So I don’t want to discuss the details of Trumpism. It’s just that he clearly signifies a discontinuity.

Joshua: A cultural shift in a very short period of time. So it’s possible.

Geoffrey: Something that we talked about this five years ago and said let’s have a virtual reality, let’s have a thought experiment. Could we imagine a transition to a state in which we will have a bunch of examples? You say, “Yes, of course that’s possible†but you know it would take a whole series of events and it probably would take 50 to 100 years and maybe we would then regress to that state that we might have been in you know 5000 years ago. I don’t want to make up numbers now. But the point is that it happened in a year or so. Now I decry Mr. Trump but he has shown that to make significant cultural social change is possible in an incredibly short period of time. Now I actually don’t believe that it’s going to survive. I don’t think that it will leave a residue but there will be a reaction to that but it may not. It may be that we moved into a completely another phase, another trend or transition to another state and that this will be so to speak the norm and many of our politicians will behave this way and our leaders and so on.

But now going back to my main point. My main point is that what we really need is some analog to an ancient Trump, meaning [unintelligible] Trump, the opposite that is someone…

Joshua: Putting the brakes on instead of pulling the accelerator.

Geoffrey: Yeah. I know I am going to sound a bit flaky or if I haven’t already [unintelligible]. In terms of we believe in loving our neighbor. We believe in collective behavior. We believe in caring. We believe that we don’t need to have more of everything. We don’t need to be the richest person and the most powerful, that it’s I could be satisfied with my one car or even two cars and buy one home with four bedrooms and a kitchen and a whirlpool and that’s enough. Enough is enough already. I earn you know maybe I earn 250000 dollars per year or 50000 dollars a year whatever. And I you know I can live or be satisfied to a large…

Joshua: I can’t have everything so I might as well enjoy what I have and increase my joy.

Geoffrey: Yes. So let’s return to a state that once existed where people were much more content with what they had. Now those states I don’t want to return to that state because people were horribly exploited. So the real question is can we have the benefits that have come from this extraordinary period of capitalism in 200 years of entrepreneurship and have those benefits and continue to develop ideas and innovate without growth and the consequences of that growth leading to a destruction of our environment including climate change and enormous social stresses that incurred and have so to speak [unintelligible] too? And I think the only way to do that is if there is a major cultural global shift. So it needs, I know this sounds really flaky, it needs sort of a charismatic figure like Donald Trump.

Joshua: Now I’ve got to cut you off here because when Trump got elected is when I thought I got to do something because I don’t think he’s going to do for the environment what I think is important to do for the environment. I think it’s going to the opposite direction of what I think is important. And I thought OK I’ve got to contribute here, I’ve got to do something because that’s when I realized that big changes of this sort have not come from inside government. And I think of Mandela and Gandhi and Martin Luther King and Vaclav Havel.

Geoffrey: We need Mandela’s, Gandhi’s, Jesus Christ, whatever, we need…

Joshua: Siddhartha.

Geoffrey: We need these kind… Someone of that charisma stature and on this more humanistic side.

Joshua: And so when I saw this happening I said, “If no one’s doing it…†Like I thought Greenpeace, they’re not doing it. Environmental defense, but that’s not quite right. I thought no one’s doing it. I’m going to do it. It sounds crazy but you know long before I ever met you I was saying if we need a Mandela of the environment and there is no Mandela of the environment, I’ll do the best that I can. I keep telling if you could do it better, if you think I sound crazy and you could do it better, do it. I’m more than happy for someone else to do better than me. But until someone does it better I’m going to do the best that I can.

Geoffrey: Keep doing it because very few people are doing it. That’s the sad thing.

Joshua: And the crazy thing is that what began as… Every single thing that I do begins as something environmental and I don’t do any of these things because of the environment anymore. I stopped getting packaged food because I don’t want to produce litter. And now I do it because it’s delicious. I stopped flying because I didn’t want to pollute but that’s not why I don’t fly. I don’t fly because community and adventure and cuisine comes more when you develop the skills to create these things and making this podcast began as something environmental. But it’s not, it’s about meeting people like you and what I’m sharing is not “Let’s protect the environment†although that is what leads to. What I’m sharing is joy and love and harmony and I don’t want to sound flaky either but that’s what I’m getting and I feel like I want to help people make that transition and have them not feel like… You know you talk to a lot of people about this stuff and they start feeling guilty and then they get protective and push back. But I felt once I realized that I felt guilty that the guilt was coming because I was living because my values and the way it to go away was to stop pushing it down, acknowledge it and say what’s causing it. And it was behaving one way and believing another and then saying, “Well, changing the value hasn’t worked. Let me change my behavior.†And that has made everything better.

Geoffrey: That’s fantastic. No, I understand. I’m not good at that. I am good at some things we talked about. And I am even good at being you know speculating is what I was doing. In the last 15 minutes has been quite speculative. But I think it’s incredibly important to speculate about those but even more important to act. And I completely agree with that and I don’t think I’m very good at that. I mean I try to do some of these things but I’m not a leader in that sense. I like to think of myself, I know it’s a bit ivory-towerish, this hopefully providing the tools or the framework and the way of thinking and to inform how we can proceed and why we should be doing these things and maybe even try to formulate works that uture might and could end up being both in terms of its negative and in terms of its potential positive, the glorious world we could have versus the collapse of the entire fabric.

Joshua: That was quite understated, the collapse of the entire fabric. So you know the reason I had on the tip my tongue Schrodinger and Crick and Feynman was that once I started looking at leadership I started looking at this was something that I think people looked at us like, “This woo-woo. You got to be born that way. You can’t learn it†and my physics application to it was, “Yes, you can.†This system it’s not trivially simple but there’s plenty of ways to teach it that you can learn the skills of self-awareness and things like that and empathy and compassion and how to practice these things and that’s what I’ve been doing for the past several decades and I’m really curious if the super linear property is causing this open-endedness than this I presume somewhere where it’s linear where… And I guess we want to get to sub linear…

Geoffrey: You want to get at least to linear. That’s what you’d like to get it. [unintelligible a little bit even something actually technically you can be just a little bit super linear, it would be Ok. Believe it or not.

Joshua: Let’s give ourselves a little cushion. The question in my mind is does getting that exponent to where we want it to be does that tell us properties of the system that we want?

Geoffrey: I don’t know the answer to that.

Joshua: That would give us a target.

Geoffrey: Yes. So that’s what I would like to be thinking about and I do think about but I think we need much more focus and attention on things like that. But in particular you know my efforts have been much more trying to sharpen and formulate the conceptual framework and the way of delineating this within a scientific framework. So that puts us in a position to begin to answer that question. And I invented this bizarre phrase that what we need is a grand unified theory of sustainability where all these things come together and that involves everybody, by the way. That’s not a physics thing but it’s everybody that has a stake in this that is thinking about it including politicians and policy makers and media people and you know economists and biologists and so on. We all need to be involved, and climate people and so on.

And you know I actually when I wrote a short article about this, I first suggested some years ago it needs to be something that has the [unintelligible] imperative of the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb all the excitement and the reach for the Apollo project only you know 100 times bigger because frankly the prospect of what could happen to the planet if we just blindly go on makes you know something like the horrors of the Second World War slow. Because it could be the destruction of kind of socio-economic life as we know it. So this has already destroyed human beings…

Joshua: We will be back to subsistence living…

Geoffrey: Yes. And of course, it will manifest itself. If we start moving into this phase, it will manifest itself as social unrest or more. And you know the worst thing that can happen is that degenerates into the use of hydrogen bombs and so on in which case then life itself is threatened, I guess.

Joshua: Well, human life. I imagine bacteria… I mean stuff under the oceans is still going to keep going.

Geoffrey: I suspect life can sustain that. And I can deal with that but certainly human beings won’t survive that. It depends of course on the scale of how many bombs you drop et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. I mean we’ve been speculating up to now. This is beyond speculation.

Joshua: So let’s leave that because that also runs the risk of people saying, “Yeah, well Malthus said that too†and that leads to like this kind of jujitsu that it’s been played up many, many times.

Geoffrey: I hate that. I hate that. When I talked at a symposium put on by the Economist magazine journal and I was interviewed on CNN New York actually and I was interviewed on stage by the editor. And it was extremely good the whole thing when he suddenly had a moment and he said, “My God, are you trying to tell me that you are Malthusian?†And he said it as, “Are you trying to tell me that you’re you know a child predator?†You know I mean it was like the worst insult that he could imagine.

Joshua: Economists love to… Yeah, they are like, “Well, he was wrong.â€

Geoffrey: I said, “No, I’m not a Malthusian actually but I am a neo-Malthusian.†That is that Malthus got it wrong. And I think so did the [unintelligible] people as the Ehrlich [unintelligible], they got it wrong because and they were highly criticized for it as opposed Malthus by the way originally that we will innovate, we continue to innovate. And that’s what we do. We do it. We’ve done a fantastic job. Paul Ehrlich predicted that India would collapse within a few years, by 1982 or something.

Joshua: And if we’d stayed on that same trajectory without innovation we probably would have but we kept innovating. So Green Revolution and so forth.

Geoffrey: We had this marvelous revolution in agriculture and so on. So this has happened that we’ve been unbelievably clever. But the thing that people have not appreciated, first of all, they haven’t appreciated the mechanisms underlying this. But most importantly they haven’t recognized that time is speeding up. If we don’t operate by the spinning of the Earth on its axis and the Earth going around the sun which is on this watch of mine. We operate by our social interactions which is getting faster and faster. We can’t keep up. Most of us [unintelligible].

Joshua: So we do interact by time of the Earth going around the sun and so forth in one way but the development of our cities and our social structure is that operates…

Geoffrey: [unintelligible] life has now this other timescale associated with it which is not constant by astronomical time, it’s accelerating time.

Joshua: So we have to act on our social structures and that’s what I’m trying to do.

Geoffrey: Exactly. You’re doing it. You’re doing it. I’m not. I do it at some pathetic small level.

Joshua: One of the things that I also realized was that looking at what I’m doing from a systemic perspective if I change, that really does nothing in terms of a billion people. If I get people around me to change, that’s still nothing. If I get the entire United States to change, it’s still not that much. 300 million people or so is not that much compared to billions. And I realized I’m not at a leverage point of a system.

Geoffrey: No, that’s why Trump gave me…

Joshua: Oh, yeah. He’s at a leverage point of a system.

Geoffrey: He really was one of us. Look, no doubt watch the debates, even the Republican Party. He was trashed by all those people who now love him and adore him, their hypocrisy is unmounted. It has reached the maximum level that’s allowed by the … I don’t know what. It’s unbounded. And he was singular. He was in some ways he was a genius.

Joshua: Can I say? Nelson Mandela from prison negotiated with the presidents of the country and got their jobs.

Geoffrey: So it’s amazing there are these people that you know have an extraordinary talent and many of the ones we are aware of, many of ones that we admire did it for what we define or perceive as the forces of good and boasted the forces of good means that you improved a lot of everybody. That’s sort of you know the quality of life, making life more meaningful for people and so forth. And you know there’ve been a few people with this kind of genius, this charisma, this way of tapping into some…

Joshua: And we’re talking Siddhartha Gautama. We’re talking Jesus. we’re talking…

Geoffrey: Yeah, we are also talking of Hitler…

Joshua: Stalin.

Geoffrey: You know there are such people. And we do have many dictators and so on who behaved very badly towards the populations that are come on from time to time and more of them now that they’ve been in the past. And Trump is certainly not a Hitler but he has you know he’s certainly an autocrat and so on. But more than that simply his values and his sense of what is right and wrong seemed to be at odds with what we defined in at least I [unintelligible] of Western culture and certainly of the ideals of what made America great country. You know the belief we all have as Americans from the very beginning believed in science. We are one of the great Americans for maybe all its faults believed promoted science like [unintelligible] and Thomas Jefferson was fantastic.

Joshua: I thought you would say Ben Franklin.

Geoffrey: But Ben Franklin wasn’t a president. That was sort of the beginnings of this country. But it’s been part of Western culture.