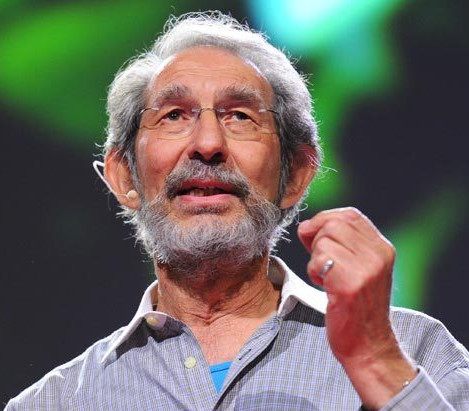

103: Geoffrey West, part 2: theoretical physics and the environment (transcript)

In my second conversation with Geoffrey West we go from talking about the scientific observation and theory that he came up with and wrote about of the past and we extrapolate into the future. This is something that he wanted to do. His book went in this direction but he kept conservative and you’ll hear him say that he wanted to go in this direction but he didn’t really go that far. The thing is that nobody knows any better. Personally, I think this is the role of a scientist in our world situation where we have environmental crises and the scientists know things best. Now, are they the best leaders? I’m not so sure. Do they know a lot more than the average person does about what’s going on and what we could do? Yeah, I think they fit the bill. So we talk about science and culture and the environment and the role of scientists within the culture today and scientists like Galileo and the legacy that they left for us. I think Geoffrey West listeners probably like listening to science and projections from it, not out of talk, so I leave you now to the conversation with Geoffrey West.

***

Joshua: Welcome to the Leadership and the Environment podcast. This is Joshua Spodek. I am here again with Geoffrey West. Geoff, how are you doing?

Geoffrey: Very fine, thanks. It’s great for you to have me back, Josh. I am looking forward to it.

Joshua: Great. And I want to jump right into things. What I’d like to do this time is to begin where we ended last time. So you walked us through your research. Of course, we’ve barely scratched the surface. I’m reading your book now and I love it so, people reading it, it’s engaging from the start. And I mean I have a science background. But I said this before and I’ll say it again you don’t need a science background to get the stuff. It’s very accessible. And it’s lively and these graphs that he talked about last time are there and they’re right next to each other and you can see how closely these things follow these lines and you are like, “This is amazing.†So one, everyone should read it and two, what I’d like to do is talk about your thoughts on applying what you’ve come up with like what recommendations you have. Also, your feelings on it. And is that okay to talk about?

Geoffrey: Oh, yes absolutely. I’m happy to talk about it but I do want to say right upfront this is obviously moving into a different kind of territory. Almost everything we talked about last time until the very end was what I would consider a solid scientific basis. I’m talking as a scientist and now you’re asking me to take that and project and speculate into the future in terms of addressing these multiple problems that we face. And obviously, as this work developed and certainly as I was writing the book this kind of question arose obviously you know what is this leading to and how can we address it, how can we mitigate the threats and so on. But I never came to any definitive conclusions and in fact I found myself, actually I should say inhibiting serious thought beyond… I have lots of conversations with many people that have seen my work or read the book or whatever. So it’s been there and in fact one of the reasons I think I would be enthusiastic actually about having this kind of discussion is that it’s I am gradually beginning to think that this is something I should think about more seriously and either write about more seriously. And it takes me into new territory simply because I’m a pretty conservative scientist in the sense that I don’t know… I obviously have to speculate otherwise you can’t create but I am very reluctant to move into areas where I don’t have the kind of training and expertise that I have in terms of the things I wrote about in the book for example which covers a very broad territory but it starts [unintelligible] in many areas where I don’t have the expertise you know economics, social sciences and politics etc. etc.. So I’ve been very reluctant.

On the other hand, the many people that one perceives as gurus in this also suffer from that. In fact, off the record even though this is on the record, a lot of that is sort of bullshit in the sense that it is based on intuition and speculation. So as I said I have been reluctant to engage in that but I am now going over that threshold and I am willing to do that. But that means this conversation will be a little bit ADD and not linear.

Joshua: That is totally fine. And I know that from a scientist’s perspective a lot of times if you speculate outside of what the data suggests in conventional science view is, “Well, that’s not science or something like that.†And so I hope that anyone listening to this is you’re taking off the scientist hat and putting on just a regular human hat and you’re offering a view that others don’t have based on research and based on information and perspectives that others don’t have. But it’s distinctly relevant and I hope that anyone listening give a check get out of jail free card that he’s going to speculate as a citizen as opposed to as a scientist, I think. And I am going to start with a general question I’ve been thinking a lot of because I think that when I was practicing science it was about getting data, it was about building a satellite, it was about getting into orbit, getting the data and analyzing it and now I think when I look at the environment and I look at some issues that seem to be crises possibly looming, I mean the data could be off but it looks like there’s some crisis looming. And I think if scientists understand it more, simply taking data and publishing data I think the role of the scientist is in a situation like this where they know more than others. And that simply publishing data I think there’s nothing wrong with that but I think there’s another role of scientists. And the more I think about it which is to actively do things and not just to say, “Look at this data. You should pass a law.†but to take on leadership roles. Then looking back you know Galileo took on some pretty big social causes. You know he did some big things and I don’t think Rachel Carson was anything less of a scientist. I think she did some very important scientific things as did Linus Pauling or Albert Einstein. And so I think it’s not like a crazy thing to think a scientist’s not just producing data and writing papers. Do you think the role of a scientist today is the same, different than ever before? And time today suggests that the role of a scientist should be different today. Has it always been the same? What do you think of the role of the scientist?

Geoffrey: Many things you brought up there which are extremely important but… So first, before we get into just wanted to say, not correct, maybe elaborate a little bit on what you’re saying about what scientists could just publishing their data and so on. I think the other, perhaps especially in terms of the kind of issues we’re facing, the other absolutely critical role of the scientist or of science I should say is to create theories and models and concepts and a framework for informing how to deal with various problems. And that could be… In the past science informed as how to ultimately build an airplane or to build ships or to create the Internet and so on. And now the question is how can science inform us in terms of solving maybe the biggest challenge we’ve ever faced and that is can we ensure the long-term sustainability of the planet and the system…

Joshua: And the people on it.

Geoffrey: ..that we have evolved in the last 5000 years keep that quality and standard of living and keep it integrated with the natural environment in a way but regional benefit and continue without the very system itself having built into it its own destruction so to speak. And to the last part of your question I think the situation has changed. Of course, science has often been taught to us in a certain sense losing its innocence with the atomic bomb where there was that huge dichotomy between you know here we have a huge [unintelligible] which was perceived as a major challenge existential in a sense a kind of system that we want to deliver namely the threat of Nazi Germany dominating the planet. And the idea of galvanizing the power of science and some of the greatest scientists to create a weapon that could stop that from happening. And it had extraordinary consequences, in some way it did play important role in stopping it from happening. But it had some very deleterious consequences in the sense that scientists were… The question is are the scientists just the people that deliver the bomb and then leave it up to everybody else to decide what to do? That’s kind of the black-and-white image. But even during the Manhattan Project there were people scientists working on it who said, “No, we need to play a role in that. We know more than anybody else the extraordinary destruction and consequences that this bomb if actually used would create.†And instead of just willy-nilly dropping it on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, so to speak, unworn we should give a demonstration to show the Japanese what the problem was.

So scientists there were entering into a political discussion and they were rejected. They were completely essentially ignored basically. And that has now led to much more self-reflection on the part of science. I mean after all the whole genomic revolution which we’re undertaking now, even may I say the whole internet revolution which we’re seeing played out in front of us it’s now out of the hands of the scientists and engineers that created it and it’s in the hands of the entrepreneurs and the corporations and the individuals in this case as well as governments to decide what we’re going to be doing with that. So now going back to the situation that we want to talk about which is this question of sustainability and our impact on the environment and so on and so forth. Again, you know there’s an enormous amount of science going on.

Joshua: Oh, sorry. I don’t want to interrupt but I have to interrupt for a second. Not just looking at sustainability but in particular bring to bear the scaling of what you’ve discovered and what you’ve seen because that perspective is new for almost everyone.

Geoffrey: Yes. So my own work and the book was written with this in mind was to present a really a truly integrated view of nature to see that it’s not all random and capricious and arbitrary, that everything is actually interconnected and in a kind of course framed way is obeying some extraordinary laws. And we understand where those laws come from, why they arise, they arise from dynamics and structure of the underlying networks. But these laws operate not just in a biological world but operate in our socio-economic world and they have dire consequences if we take them so to speak to their logical conclusion. And those are that the system is simply not sustainable and that it will inevitably lead to collapse. And part of that is the dynamic that emerges to do with the increasing pace of life that life is continually accelerating and it’s becoming increasingly difficult for us not only to innovate fast enough, to so to speak to keep up with ourselves but we can’t keep up with the innovations because we’re stuck with the same body and brain that we had 100000 years ago. And maybe one of the truly, truly great miracles of human beings is that we have been really able to keep up so far. I mean it’s incredible but we’re all feeling it and that anxiety is causing lots of problems.

Joshua: You said that system leads to its own destruction. To say the system leads to its own destruction doesn’t mean that we have to stay within that system.

Geoffrey: Exactly. So that’s the very question. The question is how do we get out of this? Can we find a way of getting out of it? When I wrote that book, I tried to explain all this and my last chapter was entering exactly into this territory and trying to articulate why we’re at a critical point and why it is that we have very little time left. And I then left the strands open. I did not try to address in that the question of what would be the outcome if we don’t do anything even though it was implied. But more importantly to this conversation is what can we do to intervene. And we touched a little bit on that at the end of last time because… Let me go back. First of all, if we don’t intervene in the sense that we change something fundamental about the system that we are engaged in which is a reflection of our own evolutionary history, I believe actually, which makes it quite daunting, but if we don’t do something dramatic, then the system as I say seems as if it cannot be sustained. And what that I believe will lead to the first signs of that will be increasing, unravelling of the social fabric meaning more and more disaffection, more and more demonstrations and ultimately more and more Syria’s and Sudan’s and so on. But I think that will be happening more and more in developed countries as well as those of the highly developed.

Joshua: And that prediction is not based on you reading a newspaper and saying, “I see what’s happening in Syria. It’s going to happen here.†It’s based on…

Geoffrey: Right. It’s going to happen… Yes, so indigenously to us. I see…

Joshua: Because of the pace of change…

Geoffrey: Yeah and I think some of the things we’re seeing around the globe in societies where the standard of living is higher now than it was 50 or 75 years ago yet people are unhappy and frustrated and inequality is growing, et cetera. I think the politics that we see is the first signs of this unconscious realization of what’s been happening. Many people are being left behind but a lot of that driven by this accelerated pace of life that things are changing so fast and only a small number of people relatively speaking are able to adapt and benefit from that whereas large numbers aren’t and are becoming increasingly unable to adapt and are being left behind and eventually that pressure cooker is going to potentially explode.

Joshua: Is that a prediction of your research that the pace of change will improve things but for a small class? Because it sounds like Marx but if it’s coming from a totally different place, then I would say OK, it’s a coincidence. But I’m concerned that some people will say, “Oh, we’ve heard that before.â€

Geoffrey: I’m not a Marxist, by the way far from it. And in fact, one of the ironies that’s what I was trying to imply before I believe in terms of studying history, I believe in capitalism, I believe in entrepreneurship. And I think that it is though the combination of that and it’s derivative which is wealth and idea creation, innovation in general has been unbelievably successful but built into that is increasing pace of life and built into that is that very system that creates wealth and ideas, creates a faster pace of life, built into that is its own destruction.

Joshua: How does faster mean that some people get it and some people don’t? Some people get the benefits of it.

Geoffrey: I don’t believe it’s necessary that we have to have, well, first, inequality I think is inevitable. Some inequality is inevitable. It’s very hard to imagine a system where some inequalities don’t prevail. So it’s a quantitative rather than qualitative statement that when you have this runaway pace of life and when many people are simply unable to keep up with that it’s inevitable that… This is not science now. This is my intuition from the theory is that those that are able to adapt which means those that got onto the I.T. bandwagon and the media bandwagon for example those people adapted extraordinarily well but that left behind over 90 percent of the population. And the best that we could do, we being the 90 percent maybe, is our adaption well, of course in bolstering how to do iPhones and use Google and to presumably use Facebook and so on. But you know that’s going to get more and more. And I just don’t think people are going to be able to keep up with that. It’s not I don’t think. It’s clear people aren’t able to keep up with that. I think we’re already seeing some of the cracks appearing in that kind of stuff and I think it’s not clear that we could move into whatever the next phase is. And this is the real question in a smooth way and have kind of a soft landing into whatever that next phase is which we can discuss in a moment.

So that’s why I said at the beginning I don’t consider this as a necessary conclusion from the science I’ve been involved in but it’s highly suggestive. But what is also highly suggestive is that the way human beings in the past when they felt things, especially in our society now, stagnating… And by the way, a lot of this has to do with relative status. I mean the American Dream which flourished in particular in the years following the war so the post-war period especially up until maybe the late 70s was an extraordinary period of expansion, it was a period where the suburbs and the middle class flourished wages continue to rise in a regular way so that way [unintelligible] the workplace. Even though I was just an academic. I just assumed I would get at least a 5 percent raise every year in perpetuity and that implicitly and the platitude that my children would be doing even better than I kind of image. And then we’ve stagnated in terms of “we†meaning some 90 percent of us or whatever that number is and things have started to reverse a little bit. So the stagnation coupled with the top, people say 1 percent, but maybe even 10 percent who managed to keep up on that treadmill and benefit but benefit extraordinarily from the successes of the last 30 years. That, the relative condition of stagnation versus extraordinary growth is I think what the real problem is. It’s not an absolute scale because the absolute scale now of the middle class is probably higher than it was 50 years ago.

Joshua: So is it like saying if I have 100 people in a room and each of them has ten dollars, then there’s 100 times ten so there’s 1000 dollars? If one of them has nine hundred dollars and the remaining have a dollar each, whatever, then for 99 people that’s the same as if everybody was really poor.

Geoffrey: Well, there’s also another difference here. I think there’s another dimension to it and that is… Let’s make it more than one person. A few people get most of that 1000 dollars. I think part of the culture has been that if they did it fairly, if they obeyed all the rules and they were extraordinary clever and they did things that benefited somehow the rest of us even though we weren’t getting as much of that 1000 dollars, if they did all that and we perceive it that way, I think people can live with that. I think that the thing that also started to develop in the last 30 years is that it was perceived that a significant part of those that got bigger share of the pie were doing it in a way that wasn’t obeying the rules or were benefiting from the ills of the rest of us. That was you know, after all, people resent the fact that many bankers and investors and hedge-fund people made a huge amount of money out of the collapse of 2008. And that does not go over well. So there’s a feeling that they somehow cheated on the system.

So I think there’s a whole another dimension to this which is much harder to quantify I think because it involved judgment calls whether people are behaving badly or criminally or outside the generic culture that’s much harder to quantify. And I think people do resent that. I think that is something that causes incredible social resentment. And in the past at least across the globe has led to things like riots and revolutions and so on. I mean, my God, America as an independent country came about from I mean it was a lot of things were happening but the seed that made to thing erupt was the famous tax on tea. That the British, I am British but the British American Colonials who were British [unintelligible] them by unfair taxes and they were giving nothing back. They were taking the money but not giving anything back. So people I believe and there’s lots of research on this are pretty good at living with inequality when they feel the system is fair, people are not doing it unfairly, criminally or covertly and [unintelligible] are giving back. And so people are you know Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford were not very nice people. But in American history we respect them because the fantastic things they gave back. Libraries across the country are from Carnegie. The Ford Foundation and all this great stuff… These people were extraordinary philanthropists and so they’re sort of forgiven in a certain sense even though Carnegie did some terrible things to the workers. It’s a very bad history to that. But people I think there was this sense that not only were they trying to get rich but they were also wanting to be good in a sense, maybe out of guilt. I don’t know. It doesn’t really matter but they were doing it. And I think there’s a sense now that… “Look what’s going on now. I mean this Manafort case with Trump’s campaign manager who it’s hard to believe they could be so open about their criminal activity. But they weren’t interested in giving back as far as I can tell. They were only interested in gaining power. And many of us feel bad about our present.

Joshua: So these are the things that happen partly as a result of things changing faster and faster and it’s more and more difficult for people to hang on. And you talked before about what could we do. And at first, we thought changes would take an X amount of time. Now you see change happen in the opposite direction but things happen quickly. You also said you don’t see yourself as a leader. If you were a leader, what would you do or what would you recommend to someone who is taking a leadership role?

Geoffrey: If I were a leader, several things. First of all, in terms of this issue, I mean there are many other issues, of course, all of which are connected in terms of the big picture. So one of the things is I suppose, well I wouldn’t say a leader but if I were able to be someone that plays a central role in the allocation of resources and funding in order to make changes in society, so let me limit it slightly. Certainly, one of the things is, this may sound very parochial and out of self-interest but I would certainly promote much more science and technology and have government playing a lead role in that. And there are certain things that government can do in that sphere which the free market system and industry can’t do because one of the things, one of the bad, very bad things that has happened in the science and technological area in the last again 30 odd years is that it used to be that the many of the major corporations and the most famous which was Bell Labs AT&T was they had very powerful and extraordinary research labs that not only were there for their own research and development but allowed a great freedom in doing basic research with the understanding that ideas you could never predict where some of the great technological changes are going to come from in terms of the new ideas that are being developed.

Joshua: But they do come. If you support basic science, it’s inevitable that they do come.

Geoffrey: And that’s been the history of the planet. You mentioned Galileo. I mean after all he was supported to some extent because his ideas about thinking about motion were able to play into military kinds of ideas for the shooting of cannonballs and as the prediction is where they’re going to go and design cannons and machinery to that effect. I mean that’s maybe not a great thing but in terms of the positive side of human nature but important, very important and has played a crucial role all the way through to the present, of course. So these ideas develop and they develop out of unpredictable basic research where it is serendipitous and the formula put in extremely simplistic terms find the best people, most excellent people, those that creative ideas, bring them together, give them the resources and good things will happen. Leave them alone. Good things will happen. Of, you need oversight and so on but not quarterly reports. Maybe…

Joshua: Yes. So I want to give the illustration of Tim Berners-Lee working at the [unintelligible] in physics work and basically the foundation of the Internet forms.

Geoffrey: Yes. Isn’t that amazing?

Joshua: And the return on investment on that is incalculable but very high.

Geoffrey: No, that’s what’s extraordinary. You would think that the fact that the Internet came out of the search for the fundamental laws of physics, the fundamental particles, of all kinds of very arcane questions that out of that in terms of doing the experiments to try to test the theories and do the discoveries and searching, out of that came the Internet.

Joshua: And to scientists this is like, “Of course, we know that this is going to happen.â€

Geoffrey: That is you would think. You would think therefore the great leaders of the world would get together and say, “Excuse me. Back. We need to give these guys whatever they want. Now just if they need a billion dollars for this, give it to them because who now knows what will happen.†You know the same story is about the laser. The laser came out of doing atomic physics was extremely interesting affect the coherence of light that you could put extraordinary power into a beam of light which was not appreciated until those experiments were done. And in fact, just in terms of my own personal history when I was a student, I worked with who Arthur Schawlow who got a Nobel prize as the co-discoverer, co-inventor of the laser. And Arthur Schawlow one day said to me when I said to him, “Arth,†in the discussion, “You know this work is so interesting but obviously it’s going to have no influence anywhere. You know it’s sort of interesting thing of no practical implications.†And he said to me, “You’re completely wrong. This will have a revolutionary effect.†And I said, “You must be kidding.†He said, “No!†He said, “Look,†you know because we used to demonstrate to people that you could take the beam and bore a hole through a piece of wood which then was really gee whiz, he said, “You know what’s going to happen is we’re going to make these powerful lasers and they are going to be able to do that with steel. So it’s going to revolutionize the world because we’re going to make it cut steel to a much greater accuracy.â€

Joshua: Which I actually do in my artwork. I will talk about it some other time. We have laser-cut steel.

Geoffrey: I’m sure you do and people do but it didn’t revolutionize the world. What did revolutionize the world which he had no idea, he had no inkling, none of us had any inkling, that would form the basis for carrying out the Internet and everything we do. We could not be talking the way we are if we didn’t have the laser and all the marvelous things that are incorporated in this sheet of iron in front of me. You know it’s unbelievable. So who would have predicted that? And that work by the way was done by [unintelligible]. It wasn’t done by…

Joshua: I also have to jump in with… Can I tell you my story about… I think it was Michael Faraday that he was giving a demonstration of how moving this thing… Do you know this one? He’s like living this thing through some induction and he’s getting a needle to move. And he shows it to some people and they say, “Well, OK. this is kind of nice that you can make things move at a distance and so forth but of what purpose, of what use is it?†This is electricity and magnetism. And he says, “I don’t know the exact use but I guarantee that within X amount of time you’ll be taxing it.â€

Geoffrey: Yes. So the version I heard was either Faraday or Maxwell. The one I heard was Maxwell. So they are probably both apocryphal but I think there’s some truth to that. The one I heard was about James Scott Maxwell who provided the unification of electricity and magnetism, Maxwell’s equations, and in so doing predicted electromagnetic waves which is an even greater influence on our world than the laser or the Internet actually. But when he was 19 I guess he was taken to see Queen Victoria and Queen Victoria said, “Oh, Mr. Maxwell, I have heard such wonderful things about you and your wonderful work in electricity and magnetism? But tell me what use could that be?†And he said exactly what you said. He said, “Madam, I have absolutely no idea of what use it might be but one thing I can assure is your ministers are going to tax it.†And you know what is amazing is if every time Maxwell’s equations were used or mentioned from that time onward and you had to give a dollar, one dollar, it would amount to probably greater than the GDP of the entire planet by now because of its influence has been unbelievable.

But you know again. So you would think that science, basic research would have enormous support and we were doing this and now when we’re facing an existential threat and going back to your question what I would do if I had control over it, I would increase enormously the science budget, the education budget and one of the things that I would do in that context is I would really try to craft a much more integrated vision of how we do science. The present model has been extraordinarily successful. I mean having individual disciplines and we tend to rip boxes around you know physics and chemistry and then in physics we put boxes around atomic physics and nuclear physics and condensed metaphysics blah-blah-blah is to start to foster greater integration because the problems we have to face are systemic problems and big picture questions and we don’t address those very well. We need to bring not just academics together, not just in terms of the scientific framework or the academic framework but to bring everybody into it so sort of broad misvision of what we mean by knowledge creation and research. By even bringing in but really bringing in practitioners, politicians, artists and so on because we all need to play a role in addressing this enormous question of our long-term sustainability. And the biggest concern to me is if I had this amount of money, if I could do this, my biggest concern would be, “I don’t think there’s enough time.†We haven’t left ourselves enough time to deal with these problems in order to understand what the dynamics is that’s going on in general in the big picture but also to solve all the various individual problems that we have to face which is the way we’re doing it now but to continue those in an even more vigorous way.

***

Joshua: OK. So the first thing is increased funding to science. Then it’s also bringing sort of like the systems perspective which will bring in a population that comes in from different perspectives and to work together.

Geoffrey: So not just within academia but broader than that. And if you actually finish my book, if you do get that far, the last chapter it talks about that and I call for something whimsical like we need to think in terms of a grand unified theory of sustainability. We need to think of it, grand unified meaning everything. Not only all the various problems seeing them as interrelated but realizing that we need multiple components of the kinds of people interacting in order to address these issues. So that’s highly non-trivial and it involves potentially institutional changes, of course.

Joshua: So I understand from what you’re saying that even if we get all that, there’s still not enough time.

Geoffrey: Well, that’s my concern.

Joshua: So what comes next? Have you thought of what would change the time horizon, what would accelerate things?

Geoffrey: That’s where we were at the end of the last conversation last time. We sort of got into that when I went off on some tangent about this whole question, we need… So pace of life is speeding up. One of the consequences of that is that we need to innovate faster and faster in terms of making paradigm shifts, major things that keep us ahead of the curve so to speak. As I said earlier even with that, we have this huge issue that maybe we’ve reached the threshold where our brain, our biology which is the same biology as it was 100000 years ago simply isn’t able to adapt fast enough to the very things that we are creating. I don’t know the answer to that. And I became very despondent because of that.

But one of the things I began to realize and only in the last year was that, I like many others, had started without thinking to identify innovation with technology. Innovation and technology had sort of become synonymous in our mundane language. When you say, “What’s the next innovation?†you immediately think of, I don’t know, driverless cars or some personalized medicine but something that’s technological. And what I began to realize is that across this whole other side of innovation which is of course cultural and social and that what is obvious and I am certainly hardly unique in calling for this is that maybe what we really need is a socio-cultural change, maybe even a political change. But we do need to think in those terms in order to address this question that of open-ended growth that open-ended growth is integral to this and is it conceivable that we can change our social interactions, our social networks in such a way that we’re not driven by always wanting more, always wanting more and always wanting something new. That seems to be part of what we have evolved into. Maybe it’s always been there but it’s been the most apparent since the Industrial Revolution.

Again, when one thinks of social changes and cultural changes one usually thinks of many, many decades for those things to happen and we may have discussed last time very simple examples that have happened in our lifetime and that is the role of cigarettes and the role of seatbelts both of which when they were first proposed that there shouldn’t be smoking in buildings in buildings and we should all wear seatbelts [unintelligible]. No one will ever change. Of course, a few people will and so forth. Well, in fact it’s remarkable. But not only is the building I’m in, The Santa Fe Institute here, all of this is smoke free but we live on a 25-acre site which has lots of trees and so on which you can’t smoke anywhere on this.

Joshua: And no one’s objecting. Everyone’s happy with that

Geoffrey: And everybody’s happy with it.

Joshua: Nobody is saying, “What are you doing? You’re pressing us. This is some mommy state solution, nanny state solution.†Everyone’s happy.

Geoffrey: It’s extraordinary. In fact, there’s only what you have to do to smoke you have to go all the way down the driveway out to the street to the road and if you walk, it’s a 10-minute walk, if you drive, it’s a minute or two and as far as I know only one person does this which is extraordinary whereas 50 years ago I would be sitting here puffing on a cigarette and the room would be full of smoke anyway because there would have been people in here smoking. That’s amazing. And certainly, with seatbelts. But that did take a number of years. That’s trivial to me on the scale of the kind of change we’re asking in terms of solving this issue. So I was not very confident that we could do this. I was confident that we could do it but not confident that we could do it in the timeframe of 10 years or 20 years.

Joshua: Before the social fabric started unraveling things.

Geoffrey: And that’s what we talked about that last time I got this loony idea that you know Mr. Trump has given us an example of where it looks like maybe you can make a cultural change in one year. I don’t know whether he’s made a cultural change but if it persists, if Trumpism says, then he’s made it. But that transition from believing in rational discourse and telling facts and not sort of making them up on the fly as suits you and believing in science, believing in scientific discovery and so on and even being civil, I would say, all these things that we thought were sort of ingrained in our culture… Not that we didn’t know that all these things existed and in fact exist in all of us. You know I am just as prone as the next person to have all kinds of horrible thoughts in my head in highly emotional moments but you know part of the role of the culture and part of the role of law and part of the role of being social creatures is that fabric is the thing that stops that erupting and it’s been unbelievably successful for a very long time. And what it does erupt, it tends to erupt in a highly collective way in terms of the things we were talking about early – revolutions and violent revolutions and wars. But you know on a day-to-day basis it’s pretty much kept under control. And that’s wonderful that we want to encourage that. And he sort of let the genie out of the bottle and this thing popped out and large numbers of people…

Joshua: So without going into the details of what he did I think you’re saying that the pace of change that he was able to demonstrate, that change on this scale could happen in a very short period of time and that gave you hope.

Geoffrey: That’s what seems to have happened. This happened in one year. You know when he first ran for president people thought it was a joke. And not only that, his contenders in the Republican Party some of whom are very right wing were absolutely trashing him for these things. Now everybody goes along, 50 percent go along. So a huge transition took place. Whether it persists, I don’t know.

Joshua: So what you were saying just before this was you’re saying that you associate or it’s common to associate innovation with technology. There’s also cultural innovation and cultural innovation can happen quickly. And I want to ask the question what specific changes do you foresee would be effective?

Geoffrey: Well, I don’t know the answer to that but then again it sounds a bit fleetly that the values, the sense of values that our society is built on, and I would say is predominately what American society, I mean the American Revolution and the Constitution, the Bill of Rights and so on, all those things that we’re built on, that we actually believe those. People actually believe them. You know the famous thing that in the Vietnam War world and all the demonstrations and all the rest, the country was also in a very divided state. There was a wonderful survey done where people would take the Bill of Rights and show it to people and ask, “What is this?†And it was something like 70 to 80 percent said, “It’s a communist doctrine.†It’s not recognized because people don’t know what it is. They don’t realize how phenomenal and truly revolutionary that Bill of Rights was.

So we need to live that in some way. So it’s in other words to the change we need to move much more towards altruism, much more towards a more collective understanding of the problems, we need to move much more towards having a truly educated public. Somehow, I don’t know how we do that with the invasion of social media and so on. But this is what the anti-Trump revolution would mean that it’s not actually revolutionary. It’s returning or living the values that are typically embedded or are embedded in our Constitution, the Bill of Rights and in our multiple religions, whatever they are. Almost all religions love-thy-neighbor-as-thyself kind of image. And those kinds of things I think we need to somehow have a leader, a charismatic leader, someone with the same kind of force of personality and charisma and deep intuition that Donald Trump has which is phenomenal, I say. Someone with those characteristics that can lead us in the other direction. And of course, [unintelligible] kind of Nelson Mandela, Jesus Christ, I don’t know, Buddha, Martin Luther King, etc. that have that kind of moral potion. And that person to understand that the problems we face are somehow the moral equivalent of war.

People are very easily galvanized, it’s platitude, very easily galvanized by war. You know people said it was the best thing that could happen to us is an invasion by Mars. We all come together at last. So what we need to recognize is that the issues we face is a moral equivalent to war. We need to have that kind of sense of urgency and a leader. It can only be done in some way by this kind of charismatic leader. I mean Trump certainly extraordinarily, brilliantly picked up on a malaise that had been developing over quite a period, long period of time which as I say I associate with just this accelerating treadmill actually. But he picked up on that and has exploited it in many ways but gave vent to that frustration and we need someone to counter that in a similar way to recognize that all these multiple problems need to be addressed in a serious rational way and in a way where we do it communally, collectively and in a way that promotes love and respect rather than hate and disrespect which seems to be part of what’s happening now across not just Mr. Trump by the way but across the country and across the globe and is part of what’s happening.

And by the way, I said this earlier but the very fact that much of this dynamic seems to be going on to varying degrees across the planet means that it’s not specifically an American problem. It’s not Mr. Trump and it’s not people on the right wing here with all their Tea Party and all their agendas and so on. It’s something much deeper than that. And so that’s why we have to address it in a much deeper way. And that is why going back to your question what would I do it would be to truly try to get people to understand that and so put serious resources into ways of addressing it and the only way I know about addressing it is a combination of political action and knowledge creation and deep understanding and education. I am afraid I am being a little bit platitudinous.

Joshua: We have to start somewhere. If you haven’t voiced it before, the first time you say it it’s going to come up…

Geoffrey: But you have to start somewhere. Exactly. You have to start with these big, big ideas.

Joshua: Yeah. If you don’t say it, then it’ll stay platitudinous and never refined.

Geoffrey: Well, that’s the point. And I think what you’re [unintelligible] me with is that one should refrain from saying these things and being outspoken about them.

Joshua: I am not saying should or shouldn’t. But I think that sharing them will lead to…

Geoffrey: As a scientist, because that’s how you started the conversation, as a scientist even though it’s outside of science.

Joshua: Traditionally, yeah.

Geoffrey: Traditionally. That’s the question. Should it now be part of the scientific agenda?

Joshua: Or the part of the agenda it doesn’t necessarily have to come from scientists.

Geoffrey: No. It shouldn’t. It should cover everybody.

Joshua: Because scientists are not particularly effective at motivating people. I think they’re the opposite. OK. So I got to share with you something. There’s a podcast episode I’d love for you to listen to. Most of my podcast episodes I am talking to people. I’ll send you the link after we finish. And the title is Technology Will Not Save Us and You Know It.

Geffrey: With whom?

Joshua: That’s just me.

Geoffrey: Oh, you. Very good. Very good.

Joshua: And I’ll send you the link.

Geoffrey: I am completely in agreement with that statement.

Joshua: And the end you know it’s very interesting because I think of the [unintelligible] steam engine, maybe the archetype of the Industrial Revolution and most people know it wasn’t the first invention. It was the much more efficient steam engine. And so you think, “Oh, very efficient. That means it uses less coal.†Well, each one uses less coal and then we got many more of them.

Geoffrey: Well, that’s the point. Exactly.

Joshua: And so now we use more coal than ever and what we have today is the exact, that is the result of that efficiency. And you say LED bulbs are much more efficient than incandescent bulbs. And we haven’t crossed over yet but soon we’ll be using more energy lighting things we never lit before. And so if you think that technology somehow created this situation, of course it created longevity and all sorts of other things and it improved our lives in many ways. But it also created this situation. And so if you think that somehow now pursuing technological solutions will get us out of this you know Jevons Paradox, I am sure you know the name, that is going to get us out of the cycle of temporarily more efficient but then in the long term using more. Then if you think it’s going to be different now and that means that you think something has to change from what was happening before and if something has changed, it is not the technology that does the change. And I come to the same conclusion you know it has to be our values that have to change that if you have a system that produces an outcome, say plastic in the oceans, and you make that system more efficient, you’ll produce that outcome more efficiently. If you want a different outcome, you first have to change the goals, values of the system, then work on efficiency.

Geoffrey: No, I completely agree with you. You’re putting it in a slightly different language but is pretty much what I would say what my work actually led to was that realization.

Joshua: And when you said your work, that’s got me so excited and you read this excitement hopefully in my voice now. But it also tells me that since you’ve thought about things from a different perspective that almost certainly means that you’ve come up with ideas that I haven’t come up with or you’ve come up with ideas in a different way than I have. And if time is up, maybe we can move to another one?

Geoffrey: We could continue again. But why don’t you mold it over, send me your link and maybe we’ll talk again. I mean I am open.

Joshua: Yeah. I’d love to get to more specificity. With these hour-long conversations people are… We are losing people left and right. But I think it could be amazing.

Geoffrey: Yeah. Because I am [unintelligible] and go over all kinds of tangents.

Joshua: That’s this language of basic research?

Geoffrey: And this one is one where I haven’t really thought it through well because you can’t. Because they’re just speculating as I said earlier about the future and I’m trying to draw inferences from the past but it’s interesting because I have been thinking recently and I need to think about it seriously and even write about it. [unintelligible]

Joshua: All right. So I’ll let you go. I don’t want you to be late. I’ll send the link. I’ll mold it over and I’ll schedule the next time.

Geoffrey: Please. Terrific.

Joshua: Talk to you again soon.

Geoffrey: Have a great weekend, Joshua and thanks again for accommodating my time. Take good care.

Joshua: You too. Thank you very much.

Geoffrey: Bye.

Joshua: Bye.

***

This second conversation that I had with Jeffrey led to a third which will come up soon. I consider Jeffrey’s views unique and valuable and I love the dialogue. Speaking as someone trained as a scientist to another person trained as a scientist it seems to me that we have to change the goals of our system. That doesn’t mean stopping capitalism as a lot of people need your kind of respond. On the contrary, when I look at capitalism rules like bankruptcy and antitrust legislation, they fix inherent problems of for example debt turning into slavery. So we had bankruptcy to prevent that from happening. And markets tend to monopolies so we have antitrust legislation to prevent that from happening. These we’ve widely view as something that makes capitalism work more effectively and more fairly for people. It’s a moral level playing field. That’s the way it seems to me. Markets also overproduce and overproduction is a major problem today. We’ve accepted laws fixing other problems. Why not these? It seems clear to me that this makes sense. We also regulate accounting. We don’t allow companies to lie about their finances. So what’s wrong with accurate accounting? Not allowing companies to unload their costs on me because companies all over the place externalize their costs on to other people.

Anyway. I am getting away from my conversation with Jeffrey. He was a bit light on what to do. Leadership isn’t just about a vision but how to implement it. Not just we should do X but how to motivate people to do it. So if we want to bring these teams together, how exactly do we bring it together? What do we charge them with or do we just let them go? Because I think if we just let them go, I’m not sure if things will happen on the time scale it’s important. I’m a fan of basic research, I’m a fan of science, education. I think they’re very important but I think we have enough science, education and so forth to act now on the environment. We aren’t acting so I’d love to see the team he talked about to form. I’m skeptical it will get to the results in time but the big picture is I think his view from his scaling laws I think it’s very important. It shows the problems. It shows the need for leadership and cultural change. Anyway, we will talk more about this in the third conversation coming up.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees