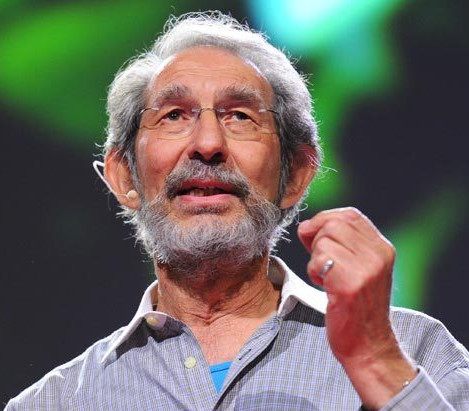

110: Geoffrey West, part 3: Using science to create a vision for the future (transcript)

I think of Jeffrey’s research as particularly valuable since it comes from different directions and draws from many different sources than most environmental approaches do. He takes a different approach to technology and innovation. He’s not so big on technology. I mean he’s big on it but he recognizes its limitations and its potential for harm. Rarely do I hear of scientists saying that their research points to leadership. In this conversation we move from research into more about action and leadership. You’ll hear I begin with a few questions: “Can we change the pattern he found and described and what does it look like?†He talks about a solution based more on cultural change than technological. He talks about how he expects it to be based on altruism and love and things like that. Not the sort of thing you expect from scientists, at least not in public. In any case, I think that Geoffrey West’s listeners probably prefer science to me talking so I’ll leave you to the conversation with Geoffrey West.

***

Joshua: Welcome to the Leadership and the Environment podcast. This is Joshua Spodek. I’m here with Geoffrey West again. Geoffrey, how are you?

Geoffrey: I’m fine, Josh. Nice to see you again to chat with you again. I just got back from a trip so I am a little bit at sixes and sevens but good.

Joshua: Well, that happens because the exponent is high and therefore you move faster than if you were living on a farm. Yeah, actually I want to get into that. So since we last spoke I finished your book and there were a lot of things in there that I wanted to cover now that I’ve gotten more depth out of it and I took some notes. And I’d like to go down, if it’s okay with you, to say a couple of things, a couple of topics and then maybe we can pick one or two to cover in a little more depth. And at the very top level for me is that I read your book as a book of… This came out before, is that your book was studying something, presenting the results of what you studied and the last chapter was starting to get into “What do we do about this?†And for me that’s a starting point and one of the things I’ve loved about our earlier conversations is that your results lead you to say a leadership would be very important right now. Ironically, Donald Trump showed that leadership of this kind of change that you think is necessary is possible. Ironic, that it happened the way.

Geoffrey: Yes, exactly. But with the wrong sign.

Joshua: Yeah. So for me it came to me because I thought that’s what was missing. And so I want to dig into your stuff for how we can use it for influencing culture. And so one big thing is that… Alright. Here is topic number one. Are we increasing the city growth, the exponent, the super linearity or is what we’re doing…? I presume that we’re keeping with it but when we have social media and we’re connecting to lots more people and we get… Is that making it more super linear? Or is there something we can do to make it less super linear, to make it just say linear. And if we do that, would that mean that we would decrease our impact on the environment? Although we would we also risk cities disappearing because that seems to be something that makes them so stable. Then another thing was coming from Limits to Growth, having read Limits to Growth, that was influential. I mean it’s one piece of the puzzle or one perspective but from then it seemed like population is really a big issue. But I think from reading yours it seems not just overall population but the population density, the number of connections that people have between each other.

And if that’s the case is… There’s you know the Slow Food movement out there and I wonder if … You know for people who don’t know as opposed to the Fast Food movement. So fast food is all about getting it really quick and whatever’s cheapest. And slow food is like what’s most delicious and best for the land and so forth. Would doing something like a Slow Life movement affect the super linearity? Is there something we can do to change culture to do that? This is what I’m thinking about. Can we influence that exponent in a way that’s beneficial and without being detrimental? Is that something conceivable? Have you thought about that?

Geoffrey: Yes, I have thought about…

Joshua: Is that what you think about all the time?

Geoffrey: No. Your first question of course we also put it in terms of the fundamental dilemma that you know the very dynamic, that is a different way to say it, the very dynamic that has led to our great success and a high quality and standard of living has built into it these kinds of fatal flaws that I am doing. And so one of the things that’s unclear is if let’s just say this let’s say we do have a mechanism for changing things. You know for slowing things down, for decreasing superiority and making it even you know sublinear so to speak but still have the kinds of things we’d like to have. Even if we could do all that, maybe by doing that we undo the whole structure that we invented and developed. And so it’s a huge dilemma. And you know obviously I don’t know the answer to that but one specific thing you asked about and that is that you know the evidence such as we have is that we just keep track with that super linearity, we’re roughly speaking the same exponent.

I don’t know if I mentioned this in the previous discussion. One of the frustrations of the work is that we don’t have access to significant historical data. All the data comes from the last best 50-60 years. We would love to have data on cities and social phenomena from you know 75 years ago, 200 years ago, 500 years ago, a thousand years ago you know to see if…

Joshua: Rome and Egypt, yeah.

Geoffrey: Now I’m confident that there is such data. It’s simply you know gathering that data, getting that beta. It’s no doubt much of it is hidden in leather-bound books handwritten and recorded and sitting in basements of various town halls and government offices, maybe, and libraries. But no one is “There should be a project and try to really to get that data so that we can answer some of these questions.â€

Joshua: So that the graduate students can get their Ph.Ds.

Geoffrey: Exactly. A couple of my colleagues, one, [unintelligible] who works with me a lot on the city work but also one about postdocs in anthropology who is now professor at the University of Colorado. They looked at a pre-Colombian urban system, the urban system in Mexico of I don’t know we call them cities but there’s very small towns and villages effectively by today’s standards and they used cruxes for various metrics that archaeologists typically use you know a number of [unintelligible] and measuring sizes of various things, size of houses and you know I’m just knowing a little bit about some of the social structure. Whatever it is I certainly don’t have the competence to judge that but these are conventional analyses done by archaeologists and anthropologists. And to cut a long story short, they discovered that in terms of socio-economic metrics analogous to the ones that we’ve used in [unintelligible] that Mexican pre-Colombian urban system scaled super linearly in the same way that ours does. And that was a very nice supportive evidence that what’s going on here does have a kind of, I’d use the word universal, application. And all the evidence seems to be that we’ve been following that.

So now what you brought up in your question, that’s why I’m addressing it, now with the advent of IT which is you know looks like a whole new way of communicating maybe that’s breaking it in some way or maybe it violates in some ways. Maybe it makes it even more super linear. Or whatever. We don’t know. And so it turns out the only data I have gotten on this is a couple of things that stupid Europe did for me. One was some analyses of Reddit data on various things and the other is on believe it or not a Hungarian version of Facebook. So this is something that when Facebook… I guess before Facebook even began I believe some Hungarian computer scientist actually had put together something that’s quite analogous to Facebook and this was across Hungary and it was extremely popular. It took off zoom like Facebook did but was then killed by Facebook. I mean in the sense that once Facebook came on and it became international [unintelligible]. But they had all the data. And what they did inspire by this work was to look at connectivity and other kinds of metrics from this data as a function of city sites, just to follow the same thing and as just look at the connectivity through this Hungarian Facebook and it is following the same rules.

Joshua: That’s what I figure.

Geoffrey: There was nothing new. That was very satisfying to me because that’s my own intuition was that it doesn’t change the super linearity because all this does come from social interaction and human interaction and that’s almost embedded in our DNA. You know it’s somehow to do with the structure of brains, the way we like to communicate and so on.

Joshua: It would simply be the next step.

Geoffrey: It just speeds everything up.

Joshua: Yes, the next step.

Geoffrey: Yeah. It’s another step in the innovation cycles.

Joshua: Or you take the line. And now the point is it’s going to stay on the line

Geoffrey: [unintelligible] Yes, it just goes further up. That’s “all†but it’s a huge step. That’s what it was doing so nothing qualitatively was changed, it was just a quantitative change of the same product, the same structure. So those two ends of the spectrum the pre-Columbia data on the one hand and this kind of Facebook-like data, Facebook Reddit type of data you know right up to date so to speak both were consistent with all of the other stuff. So that leaves the question, the fundamental question “How do we disentangle the super linear scaling from the super linear growth and how do we end the speeding up of time? How do we sort of separate those?â€

Joshua: Can we? And if so, how?

Geoffrey: [unintelligible] of cultural changes so we can have a sustainable future rather than is this you know mad rush by Lemmings over the edge of the cliff which is what we potentially are heading towards. And as you said earlier you know of this idea that we discussed that leadership in order to solve it we do need inspirational and charismatic leadership to help galvanize the forces that bring out the sense of altruism and the sense of community that people start to change their ways of doing things. So that instead of always wanting more, that we become a little bit more satisfied with what we have and adapt to moving towards in some areas at least a kind of some version of a no-growth situation.

Joshua: Yeah. And I think that if there is effective leadership, then that would say that some change is possible that doesn’t necessarily mean that we can get off that exponent.

Geoffrey: No. No, it doesn’t. But I think that’s necessary but not necessarily sufficient condition.

Joshua: And if we only stick with technology, technology will simply move us up the curve but we will still stay on the curve. This suggests that technology alone is not a solution, it would simply…

Geoffrey: No, what it does… My image is that you know… Technology from this viewpoint that is if you think of innovation purely in terms of technology and technology, new technology or new paradigm shift within a technological framework simply postpones the problem. It doesn’t solve the problem. And you know my image and sometimes when I give lectures, I give a cite of Sisyphus pushing the rock up to the top of a mountain and you know rolls down and he’s got to push it back up and that’s us. Except we’re much worse than Sisyphus.

Joshua: Because it is getting faster and faster.

Geoffrey: Sisyphus you know could do it at the same pace every time but we are destined to have to do it faster and faster and eventually that becomes impossible. That’s the kind of you know symbolic way of talking about it.

Joshua: So to me the question is can we get the benefits of cities? So New York, the average person has less environmental impact than other cities in the United States because of the population density but we’re also continuing…. We’re also walking faster and we’re getting alcoholism and all the other things. And we’re using more resources. So if we wanted to get the benefits can we have the population density without the…? Oh, and also to get animals. I mean from bacteria to blue whales everyone’s on the line. I think that they’re on the line because there’s evolutionary forces that are keeping you… They could go off the line but then they’re not going to live as successfully so either that species is going to go extinct or it’s going to get back on the curve somehow. Now people possibly could choose to behave in ways that would move them off the line in a way that cells of an animal can’t do.

Geoffrey: So that’s what we’ve done so far.

Joshua: We stayed on the line.

Geoffrey: No, we’ve stayed off the line. I mean the biological line we’ve gone way off.

Joshua: We as humans.

Geoffrey: Yes, human beings you know… Now as I think I said…

Joshua: We is like 11000…

Geoffrey: We are like a dozen elephants or you know…

Joshua: A whale.

Geoffrey: Yeah, a 30000-kilogram gorilla.

Joshua: For city, if we can get together and do it, in principle we could get a city that was off the line in a way that most of the animals generally can’t because evolutionary forces. So we just never had the awareness that as a group of citizens in a city if we behaved in a certain way, we could get off the line what would we do. Is it that we would go for a Slow Life movement of choosing to have fewer connections and yet living close to each other?

Geoffrey: Well, the trouble is it’s you know my big concern is that we have certainly evolved in a certain way biologically in a long period of time you know many hundreds of thousands, million years. But this present evolutionary trend where we became social and formed communities and cities, communities beyond hunter gatherers where we formed what became cities, this all happened in the last, really the last few hundred years. We started a few thousand years ago but the effects that we’re really dealing with primarily can be traced to the Industrial Revolution. So it’s a couple of 100 years. And this extraordinary change is taking place and the wonder of it all, to tell you the truth, is that we’ve been so extraordinarily adaptable to that. I mean it’s hard to believe that in 200 years we’ve adapted from you know being good at [unintelligible] to being able to do what we’re doing here and create the stuff and you know at my age I can still sort of learn a new act. I learn to write it in tech and so on and you know I am not saying I am amazing. We are amazing because you know it’s extraordinary that we’re that adaptable but it’s you know more and more is coming out faster and faster and we’re living longer and longer. So that seems also to be an untenable situation. So there are all these things coming together in a way that makes some either there’s going to be some you know dramatic tipping point where the whole social fabric [unintelligible] or all we’re going to you know… Iron wall. The big question, the question is or can we go through such a tipping point and have a soft landing?

Joshua: And what would it look like?

Geoffrey: Well, yes and that’s hard to know what it would look like. We don’t know. I have no idea. I mean you know some people on the one hand, on the one extreme is that you know we are all going to become cyborgs and between AI and Shinde learning and all the data that we collect and the fusion of the Sheen’s without brains you know we’re going to live happily ever after. No [unintelligible] that we’re going to live on the Moon and Mars and everything is going to be fantastic even though there might be 12 billion people on the planet. That’s one extreme version of up to a highly optimistic way.

Joshua: Except that it doesn’t fit with your data because…

Geoffrey: Of course, I think that it is going to be me. Well, it may happen in a much longer period but it ain’t going to happen in the next 25-50 years. The other extreme is the whole system collapses and we sort of effectively go back to, if we survive it all, we go back to being a sort of a version of hunter gatherers you know very much more primitive form. I don’t subscribe to either of those. And I also don’t know… It’s sort of “fun†to try to speculate what kinds of things could happen. But it’s very much in the realm of science fiction, I think.

Joshua: Yeah, because if all the technology up until now has kept us on the line, then the likelihood of a new technology… And one thing that science keeps drilling to us is if you think you’re in some special time, you’re probably not.

Geoffrey: You’re probably not, exactly.

Joshua: The chances of like the new bunch of technology getting us off the curve is very low. We’re just going be on the curve at a farther like…

Geoffrey: We’re very, very good at thinking we’re in a special time. I think I quote in the book something that was very amusing to me when I was doing the research on the book. I don’t know if you saw this part of the book where I quote John Maynard Keynes, the great economist, and also Sir Charles Darwin, the grandson of The Charles Darwin but also distinguished scientist himself, who both in the 40s and maybe in the early 50s when they were talking about the future you know they were brainstorming speculating about what the future would be and the biggest concern they had was that with the coming of all the great technology…

Joshua: Oh, the people would have too much free time.

Geoffrey: There is going to be too much time. What are we going to do with that time? And the work we will very shortly you know shrink to twenty odd hours a week and you know the big challenge for society is to provide something for people to do. And the great irony is it’s gone exactly the other way. People in fact don’t have any time to do anything. And in fact, one of the things I speculated in that book was that in some fantastically mysterious way we’ve done that in a way because what we do we maybe only do spend 20 hours a week on our real work and the rest of the time is doing horseshit like this that is we’re looking in our iPhones and iPads and watching videos and sending cute little tweets to looking up Facebook and all the rest and that’s occupying an enormous amount of time. So that was just… I brought a speculation on my part.

Joshua: I’m thinking about the exponent. What’s setting the exponent is the space filling part. It’s the connectivity, it’s the dimensionality…

Geoffrey: [unintelligible] is how we interact with the social network structure you know between us and the kind of networks that each was forms around us.

Joshua: I’m just speculating that if there were some big movement to spend more time with your mother and father and spend more time with your family and less time with hundreds of friends or thousands of friends on Internet and so forth, would that lower the exponent? Now I’m not saying it’s possible but if it did happen, would that lower the exponent to where it was linear?

Geoffrey: Yeah, well it could. So a significant piece of that idea is that there’s more and more interactions but those interactions are leading toward more and more ideas and those ideas eventually percolate into major innovations. I mean that’s sort of the simplistic way of looking at it. So at the one level it’s slowing down that process in some way and stopping it leading to this open-ended growth. And it is true that sort of mechanistically the degree of social interaction is leading in a certain causal way to greater innovations. So one has to dig deeper into ensuring that if you were to somehow, if you had a magic wand and you could decrease the social connectivity, the information that’s being exchanged is the kind of information that decreases the increasing pace of life and the increasing continuous feedback mechanisms that give rise to more and more innovations that give rise to greater and greater growth. They are all intertwined. The trouble is untangling all that is problematic but also the question is, that’s kind of conceptual question is “Can you disentangle those?

Joshua: Yeah. And I want to leave that off for now because to me the question is what would that world look like. Before knowing what it looks like, I don’t want to try to figure how to get there because I’m thinking… OK, first of all, the more I learn about reading works like yours, it feels like the more people keep thinking the next technology will do it but I feel like that’s like stepping on the gas or I guess just keeping going the way things are and it increasingly feels like whenever someone says, “LEDs are so much more efficient than incandescenceâ€, I’m like yeah, and soon we’re going to use LEDs more than we ever used incandescence.†So Jevons paradox or rebound effects. And it’s clear like the technology it would be really weird for the thing that’s causing all these problems to be also the solution. So it seems like the opposite.

Geoffrey: No. So that’s why I think it’s not technology in the end.

Joshua: It’s relationships, it is social.

Geoffrey: I may be wrong in that and it may be that indeed you know AI and all the rest of it smart this and smart that maybe you know something else will change dramatically. But one of the things that I often emphasize that people don’t realize you know we feel that indeed there has been an extraordinary change with the introduction of IT and so forth but I don’t think it is in the same ballpark even as the kind of change that was invoked by two things in the 19th century. One was the invention of steam trains, of trains, and the second, the invention of the telephone because let’s take the telephone until the telephone came along unless you were in the same room as someone else you couldn’t have instantaneous communication. And even if you were in the same town, it took typically two hours or a day and if you weren’t in the same town, it took days, if you were in a different country, it might take weeks. And it suddenly for the first time in human history you could have what we now claim we have global communication principle instantaneously.

Secondly, so you contracted time, time suddenly was contracted unbelievably. But then with the coming of the railroads you know you could where everybody was now spatially connected most people until the railroads and the introduction of relatively cheap travel [unintelligible] distances most people you know didn’t move more than 20 miles from their home in their entire life. That was the way people lived. So until that happened everybody was confined in space. So by the end of the 19th century we had opened up space and contracted time. And you know that effect was totally profound. So what did it do? It speeded up the pace of life. That’s what those two things did. So that technology made life for many people much better. But it also started on this road to open-ended growth and increasing the pace of life and creating all of these unintended consequences with which we’re now dealing and the coming of the Internet and coming of even faster communication and this kind of… I mean it is unbelievable that we could talk to one another across 3000 miles like this and see one another and so forth. It’s phenomenal. It was the stuff of dreams not so long ago. And you know we enjoy it, indulge in it but it isn’t solving the big problem.

Joshua: Yes. What would a solution look like?

Geoffrey: It’s in fact adding to the problem.

Joshua: Can you speculate on what a solution would look like?

Geoffrey: Well, my speculation is that’s why I got to where we got where we started this conversation today or where we talked last time about was that we have to… I mean one of the problems that has occurred in recent years is that the words technology and innovation became synonymous. And so we thought of innovation as soon as you think of a major innovation paradigm shift and now one thinks immediately of some huge technological innovation like driverless cars or AI and so on. So it occurred to me that the major innovation that we now need is a social cultural innovation, something that restores us to a place in our social interactions which is much more focused on altruism, on maybe slowing things, being less greed oriented. I mean the fact that much of what is happening is gathered by a very primitive form of wanting more, wanting more, wanting something that’s better than what we have. So it’s a delicate issue because that has been a driving force in human history and human accomplishment. So nevertheless, you know it is kind of weird to think that you know if someone is earning a million dollars a year, that they’d actually like to earn ten million dollars a year or if they’re worth a billion dollars, they’d actually like be worth ten billion dollars. You know it’s kind of a slightly perverse morality and ethical position as far as I’m concerned. But that’s true all the way down through society. The part of it is to want the new thing [unintelligible] more. So the question is can we change that. Because that is part of what’s driving it.

Joshua: And what would we change it to?

Geoffrey: And that’s the question. What do we change it to? Can we imagine still having that kind of vibrant exciting society where we’re still are innovating and enjoying the products of our innovation and creativity and yet not having this mad open-ended growth leading to these kinds of unintended consequences which are undermining us. And I don’t know the answer to that other than the only way to do it is if you’re going to have social and cultural change that needs also great political and social leadership. You know it has to be you know someone or some group of people that start to make you see that this is problematic, the system we’re in now is problematic and that it is a system. I think that’s the other thing that is not recognized is to recognize that all these various things that we’re participating including all of the unintended consequences are actually part of an integrated system. So we need you know also that aspect…

Joshua: People not very good at understanding systems or how to influence them.

***

Joshua: I would like to throw you a cup of speculations on my part of what it might look like because I don’t want to start trying to figure it out yet figure out how to do it because it to be very effective in going in an ineffective direction it’s not useful. You talked about some things. To me it seems like lower connectivity and moving at the pace of deliberately… Well, for whatever reason if walking faster happens, then we would be walking slower, if having lots of connectivity, having fewer connections but that would mean depth of connection. Instead of saying, “Stop making all these connections†it would be “Get deeper connections with the people you spend time with†which will probably be your family who gave birth to you and that you give birth to and things like that, and it will be so in-depth.

Geoffrey: Well, I think that’s implied what I meant by altruism. I would have also used the word love is to you know sort of can we increase love and altruism which is along those lines increase the depths of interaction rather than… In other words, the quality of interaction, not the quantity.

Joshua: So it would be a world in which people valued quality over quantity, depth over breadth, enjoyment over rapidity and not necessarily rewarding the next newest greatest thing. I mean the Amish are one example… I wouldn’t want to be Amish. They enforce it in ways that aren’t comfortable to me but as far as I can tell they’re stable and they might not be doing lots of innovation as you said but they might be very happy.

Geoffrey: Yes. So that brings us on a whole another dimension. This is a very tricky issue of course, the question of contentment, happiness, fulfillment, living a fulfilling life. These are very hard things to quantify, to measure, to judge when it does involve judgment of course. So the other question is what is under that if we want to sustain the planet or want to sustain a socio-economic life, we have to ask you know what is it that we’re trying to sustain, what are the values or the ways of being that we are trying to sustain.

Joshua: That would be sustainable. Because if it’s growth at any cost, it doesn’t…

Geoffrey: Yeah, so what’s the point? You know is it just for the sake of doing it that we are making things faster and faster and better and better. And that’s why it seems to me why we need leadership or… Well, what I called for in my book which I called for before is something so slightly [unintelligible] is that we need to start thinking about a grand unified theory of sustainability in which we bring all, all of the players involved, meaning society, to start having a multiple dialogue and multiple research into understanding what it is that we’re trying to be.

Joshua: That’s what I’m asking you.

Geoffrey: And I don’t know the answer. You know I sit around bullshitting with lots

[unintelligible]

but I don’t have any answer. In other words, what it needs… Because I do think that it’s worth spending enormous amounts of money on bringing scientists, politicians, policymakers, futurists, thinkers…

Joshua: SFI plus. Like take SFI and do more.

Geoffrey: Bring these people to really start asking are there models, are there scenarios, are there simulations where we can try to understand what the kind of society it is that we want us to be that we want to sustain. It’s a very dangerous game, by the way.

Joshua: I would not stop anyone from doing that but I think this variable is so great and the time so limited that at some point leaders sometimes have to get enough and then an act, enough to know they are not going to make some big disaster.

Geoffrey: That’s been the issue.

Joshua: Yeah but also acting too quickly or irrationally is a mistake in itself too.

Geoffrey: And so I find myself and I am in an incredibly difficult position.

Joshua: Now how about this though? I think there are situations where people expect that things could work. All these people who say, “If we trash Earth, we can just go to Mars, we can go to the Moon.†But the flight to Mars takes years. And so people who think that we can’t sustain things on earth expect it for at least several years and people can be in an equilibrium in a spacecraft. And I think that there have been civilizations that have endured for some time on modestly sized islands without too much interaction over season when you know that there’s 10000 of us and a land can sustain 10000, then at some number it seems like it could work and maybe we could take… OK, it works in small cases like that. Can we do it on a slightly bigger scale? I mean yeah, my general way of solving hard problems is to solve a simpler problem that is related and then build from that. Maybe we should just take some people on an island for a while.

Geoffrey: Well, of course you know I mean you could think of America, other parts of the world as big places where they were an analogue to Mars in a previous time where people came to form a new life and new ideals and so forth. And to some extent it was very successful obviously in some metrics. Nevertheless, this kind of dynamic which is integral to being a human being eventually took over and that has led to America also be… America is no different than any other country in facing the same sequence of problems, partially, because the problems are of global nature. So it is ironic that we have a president that doesn’t want to think globally. You know that’s why we need a kind of ancient Trump. We need to [unintelligible] and systemically in the big picture.

Joshua: I have to be sensitive to your time.

Geoffrey: Yes. Oh my God, yes, I have something in 5 minutes.

Joshua: And I can’t wait to continue this conversation. We probably won’t record it but this is tremendously valuable to me even as much as these open-ended questions are still tremendously unanswered. But at least there’s [unintelligible] to ask. And at least it rules out certain things, at least for me. And really, I can’t tell you how much I appreciate this. I have to make a comment that when you talked about that you bullshit around over there that I have a comment that I read page 340 funny remark about how bullshitting wrapped in superb PowerPoint. I love that. I hope you felt really good when you wrote that.

Geoffrey: You read that in my book?

Joshua: Yeah, it was in the book and it made me laugh out loud.

Geoffrey: Good. All because I was talking about… I think I was talking about things like TED…

Joshua: Yeah, exactly. And then I have this other thing that we’re not going to get into but I was really curious if people have worked out [unintelligible properties of cities like temperature and entropy and equivalence but I have to leave that for when we’re in person or something like that.

Geoffrey: I do have to go. I’m sorry. I realize. But yes, I have a terrible schedule up through October until Thanksgiving as we talked about last time but we should exchange stuff.

Joshua: So we’ll figure by email of how the visit will get. So if it’s through Thanksgiving, maybe I should try to stay in L.A. through Thanksgiving and try to pass through Santa Fe on the way back in December.

Geoffrey: Yes, December is much better.

Joshua: Okay, because I also looked at a map and saw how far Santa Fe is from LA.

Geoffrey: Yes, people don’t realize. We’re where the Rocky Mountains but from the Rocky Mountains.

Joshua: So coming on the way back might be better for me. So we’ll do by email and I’ll let you do things.

Geoffrey: We’ll do by email and we will arrange [unintelligible] and things, etcetera.

Joshua: Thank you very much. This is tremendously valuable for me.

Geoffrey: And I’m glad this worked. I’m sorry last time we had the frustration.

Joshua: Thank you again and I’ll talk to you again soon.

Geoffrey: Take care, Joshua. Bye.

Joshua: Bye.

***

Geoffrey West’s research and discussion points me to cultural change is what we need more than anything else, more than technological change and innovation brought about by leadership, political and social leadership and that we should be careful about technology and innovation. He’s not alone in this skepticism and care that he looks at technology and innovation from his perspective because of this rapidity of how things change. There are many knowledgeable scientists and engineers who get what he’s suggesting that technology contributes to environmental degradation even increasing efficiency. Social connectivity seems to be a problem from Geoffrey West’s perspective that it leads to rapidity and rapidity and these changes. I couldn’t get a clear statement of how lower social connectivity would look but it seems to me like slow life, if I can use an analogy to slow food. People who know the slow food movement as contrasted to the fast food movement is instead of getting things as fast as you can and as quickly as you can, as efficiently as you can, to enjoy what you’re doing to enjoy going to the farm and having slow food, enjoying slow meals. And I think increasingly of a slow life, not a slow purpose less life. But when I talk to people who live more along a slow lifeline their lives are more about meaning, value, purpose, they seem less unhappy, they don’t seem caught up in opioid crises, and stress, obesity, hedonic treadmills. You know what I’m talking about. Anyway, it’s not obvious where we should go from here but I think Geoffrey’s research points in a clear direction of slowing down, looking for technology to make things more efficient in the short term but in long term looking for cultural change driven by leadership.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees