But Aren’t We Solving Things? How can efficiency increase pollution?

I write about how unsustainability led to imperialism, which led to colonialism and slavery.

But wait. Why bring up all this awful history? Haven’t we learned from it? Have we learned from history? Aren’t we moving on from it? Look at all the things that can solve our environmental problems: carbon taxes, electric vehicles, carbon offsets, more efficient batteries, and so on. Can’t we solve each problem one at a time as it arises? Aren’t you letting the perfect be the enemy of the good?

There’s a difference between intent and effect. If nature responded to intent, I’d support all those well-meaning ideas, but nature is a complex system. Press down on a bicycle pedal and the bike doesn’t go down. It goes forward. Likewise with nature. Learn how complex systems work and we can influence them effectively. If you keep insisting that because you push down it should go down, you’ll frustrate yourself and we’ll all keep suffering more pollution and depletion.

We unwittingly use efficiency to increase pollution

It’s tempting to say technology can save us. With more power we can replace dangerous work with machines. Isn’t it obvious that efficiency reduces waste? Won’t more power and efficiency end suffering and waste?

As we know from fire and sharp knives, technology isn’t good or bad on its own. It augments the values of the people and culture using them. Human history is replete with technologies that have reduced suffering and ones that have increased it. As long as our culture remains unsustainable, technology may help in some areas, but will augment unsustainability, accelerating us on our path to collapse. We may increase material abundance and prosperity along the way, but then we’ll be rich when we collapse.

Likewise with efficiency, if you make a polluting, depleting culture more efficient, you may lower waste in one area, but you will increase pollution and depletion overall. Our technologies and markets are more efficient than ever. Our problem is overall pollution and depletion, not the percent of it, and we are polluting and depleting overall more than ever.

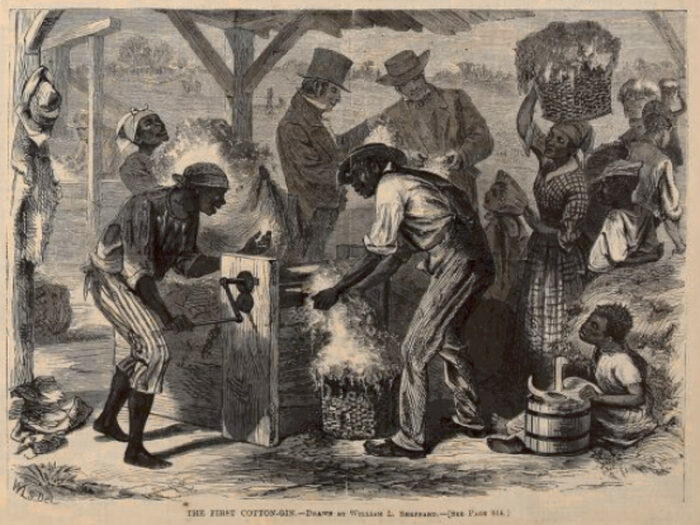

A technology in one person’s hands can have the opposite effect as in another person’s hands. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin is a prime example. He invented it to reduce labor and using it required less labor to produce a bale of cotton. People predicted it would reduce slavery, bu the people who bought them didn’t value less labor. They valued more profit and to protect and grow the resource bringing that profit. They used the gins to achieve those values, which increased slavery. Before Whitney’s cotton gin, many people saw slavery declining in America, as soils for tobacco, indigo, rice, and such were becoming depleted. Today many historians agree. Contrary to Whitney’s intent, his invention helped grow America’s cotton-producing states to the largest slave culture in history in a few generations.

Cars are more efficient than horses but switching to them didn’t decrease pollution or depletion, even if manure in cities decreased. People lived in cities of a million people two thousand years ago. The cause of manure piling up wasn’t horses but our culture. Refining oil for lamps is more efficient than whaling for whale oil. Switching to oil didn’t decrease whaling. Its efficiency accelerated other demands for whales so increased whaling overall.

Looking for the trend in today’s world, we can see it in electric cars, for example. Consider Amsterdam. You probably know it as a bicycle-friendly city. If you’re like me, you thought it turned out that way because it developed before cars. On the contrary, it was overrun with cars in the twentieth century. A big government plan developed to raze the historic city center you may think of as Amsterdam’s heart to bring in large highways like Robert Moses’s. Its citizens protested the plan, won and began decades of redesigning the city to favor walking and cycling over cars. Today Dutch citizens value clean, human-scale interactions, which their transportation and city planners implement with a strategy of fewer cars. With those values and that history, electric cars replacing gas-powered cars could lower pollution, though not likely depletion, as they only substitute using some chemicals for others. By contrast, Americans value individual freedom more, which its transportation planners implement through building more roads. With those values and that history, in America, electric cars will likely increase the number of cars, the number of roads, and therefore pollution, depletion, social isolation, dependence, and all the other problems of cities and culture based on cars.

Those distracted by efficiency miss that Tesla’s values and goals lead to a strategy of growth. Elon Musk is today’s Eli Whitney or Robert Moses, except that Whitney didn’t want slavery to grow and Moses didn’t have Moses’s history to learn from. If Tesla promoted fewer cars, Musk might be more like the Dutch citizens who protected Amsterdam from going the way of once-pedestrian-friendly streetcar towns of Houston and Los Angeles. But Tesla promotes more cars. Bill Gates, ecomodernists, and techno-optimists follow the pattern. They’re stepping on the gas, thinking it’s the brake, wanting congratulations.

In mistaking the problem for its own solution, thereby growing it, they recall the pro-slavery “Spread Theory,” that “it was necessary to extend and spread the institution into new territories so as to lighten its burden on the old slave communities.” A Tennessee convention wrote “it is expedient, both for the benefit of the slave and the free man, that slaves should be distributed over as large territory as possible; as thereby the slave receives better treatment, and the free man is rendered more secure.” Spread Theory made as much sense to them as polluting and depleting more to decrease polluting and depleting makes to Musk, Gates, and their techno-optimist and ecomodernist peers. By ignoring systemic effects, they think the next technology may pollute and deplete more, but will finally solve the problem; just don’t actually live sustainably. Consider artificial intelligence. Few can predict its effects in many areas, but many are suggesting it may solve our environmental problems. I can’t be sure either, but I predict it will accelerate our current course.

The Green Revolution is another example of the pattern. At the start of the career that led to his winning the Nobel Prize as the father of the Green Revolution, Norman Borlaug was motivated by seeing people dying of hunger from food scarcity. He worked tirelessly for decades to develop technologies to produce more food per acre of land and per unit of labor. He valued less hunger, but saw that the governments and people using the technologies didn’t value less hunger as much. Like those using Whitney’s cotton gin, they valued more profit and to protect and grow the resource bringing that profit. Like those using steam engines, they found more uses for more people. Borlaug saw the pattern and fought the latter part of his career to resist it, calling its growth effects the “Population Monster.”

Many people view the Green Revolution as having saved or enabled billions of lives, but Borlaug didn’t. For those quick to describe as Malthusian people suggesting humans could overpopulate Earth and suggest that Malthus was wrong, it would be hard to call the father of the Green Revolution itself as Malthusian and therefore wrong. At his Nobel acceptance speech he warned:

The Green Revolution has won a temporary success in man’s war against hunger and deprivation; it has given man a breathing space. If fully implemented, the revolution can provide sufficient food for sustenance during the next three decades. But the frightening power of human reproduction must also be curbed; otherwise the success of the Green Revolution will be ephemeral only.

Most people still fail to comprehend the magnitude and menace of the Population Monster. . . Since man is potentially a rational being, however, I am confident that within the next two decades he will recognize the self-destructive course he steers along the road of irresponsible population growth.

He served on the board of the Population Media Center, an organization devoted to resisting growing the population beyond the Green Revolution’s “temporary success.”

Even the tragedies of hunger and deprivation understate the problems of the Green Revolution’s systemic effects. Its technologies, however efficient, pollute and deplete fresh water, minerals, and fossil fuels.

Once you know the pattern, you see it elsewhere. Americans value more electric power and less knowing the consequences of generating it. Providing them solar, wind, nuclear, or even fusion-based power will repeat the effects of Watt’s steam engine. Despite people marketing them as “clean,” “green,” and “renewable,” they all pollute, deplete, and, for that matter, require fossil fuels and unsustainable extraction. Even if each use pollutes and depletes less, more people will use more energy for more reasons, resulting in more pollution and depletion. We can speculate that those uses will improve people’s lives.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees