Does the U.S. medical system improve more lives than it hurts, including lives outside the system?

I haven’t heard anyone in medicine question the effects of pollution from our medical system on people outside the care facility. What about people harmed by plastic, emissions, and other pollution? They may be affected for centuries and all over the world.

I don’t know anyone who calls America’s medical system unwasteful. Every time I walk into a doctor’s office I expect to see each care-person use half a dozen gloves. Many things are disposable that could be cleaned more sustainably. Talk to anyone and they say policies are for safety, but few question if their practices are safer.

In my experience, people in medicine are happy to complain how procedures waste and that “the system is broken” or “the decision-makers just say ‘it’s safer to dispose of things'”, but they get annoyed at the prospect of them doing anything about it. They seem frustrated and they know things are broken.

Meanwhile an NYU researcher studying a procedure in the UK and India found the Indian one impacted the environment FIVE PERCENT as much as the UK with EQUAL OR BETTER health outcomes:

- Reducing Pollution From the Health Care Industry

- ‘Green’ cataract surgery model drastically reduces environmental footprint

- ‘Green Surgery Model’ Reduces Hospital Environment Footprint

My question: what about the health impacts of the waste on everyone else? Since most care in the US is for the last year or so of someone’s life and extends it only a short while and the plastic and other waste affects everyone in the world:

Is it possible (likely?) that all the waste is taking more life away from people than the care is preserving?

I don’t yet know the answer, but found plenty of research about waste in medicine. I included a few links and abstracts mostly from peer-reviewed research (the non-peer-reviewed piece links to peer-reviewed work). Most research seems to cover financial waste. Financial waste still implies lost lifetime because money wasted could have been spent on care.

I haven’t found a comparison of lifetime lost from polluting and depleting versus added from healthcare. What do you think: do you think it’s overall positive? I think it’s possible, but I’m inclined to think negative, especially if we consider long-term effects of plastic that endures centuries and other pollution.

Waste in the U.S. Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework (JAMA):

Context

Health care costs in the United States are much higher than those in industrial countries with similar or better health system performance. Wasteful spending has many undesirable consequences that could be alleviated through waste reduction. This article proposes a conceptual framework to guide researchers and policymakers in evaluating waste, implementing waste-reduction strategies, and reducing the burden of unnecessary health care spending.

Methods

This article divides health care waste into administrative, operational, and clinical waste and provides an overview of each. It explains how researchers have used both high-level and sector- or procedure-specific comparisons to quantify such waste, and it discusses examples and challenges in both waste measurement and waste reduction.

Findings

Waste is caused by factors such as health insurance and medical uncertainties that encourage the production of inefficient and low-value services. Various efforts to reduce such waste have encountered challenges, such as the high costs of initial investment, unintended administrative complexities, and trade-offs among patients’, payers’, and providers’ interests. While categorizing waste may help identify and measure general types and sources of waste, successful reduction strategies must integrate the administrative, operational, and clinical components of care, and proceed by identifying goals, changing systemic incentives, and making specific process improvements.

Conclusions

Classifying, identifying, and measuring waste elucidate its causes, clarify systemic goals, and specify potential health care reforms that—by improving the market for health insurance and health care—will generate incentives for better efficiency and thus ultimately decrease waste in the U.S. health care system.

The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment:

Background

Health-care services are necessary for sustaining and improving human wellbeing, yet they have an environmental footprint that contributes to environment-related threats to human health. Previous studies have quantified the carbon emissions resulting from health care at a global level. We aimed to provide a global assessment of the wide-ranging environmental impacts of this sector.

Methods

In this multiregional input-output analysis, we evaluated the contribution of health-care sectors in driving environmental damage that in turn puts human health at risk. Using a global supply-chain database containing detailed information on health-care sectors, we quantified the direct and indirect supply-chain environmental damage driven by the demand for health care. We focused on seven environmental stressors with known adverse feedback cycles: greenhouse gas emissions, particulate matter, air pollutants (nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxide), malaria risk, reactive nitrogen in water, and scarce water use.

Findings

Health care causes global environmental impacts that, depending on which indicator is considered, range between 1% and 5% of total global impacts, and are more than 5% for some national impacts.

Interpretation

Enhancing health-care expenditure to mitigate negative health effects of environmental damage is often promoted by health-care practitioners. However, global supply chains that feed into the enhanced activity of health-care sectors in turn initiate adverse feedback cycles by increasing the environmental impact of health care, thus counteracting the mission of health care.

Almost 25% of Healthcare Spending is Considered Wasteful. Here’s Why.:

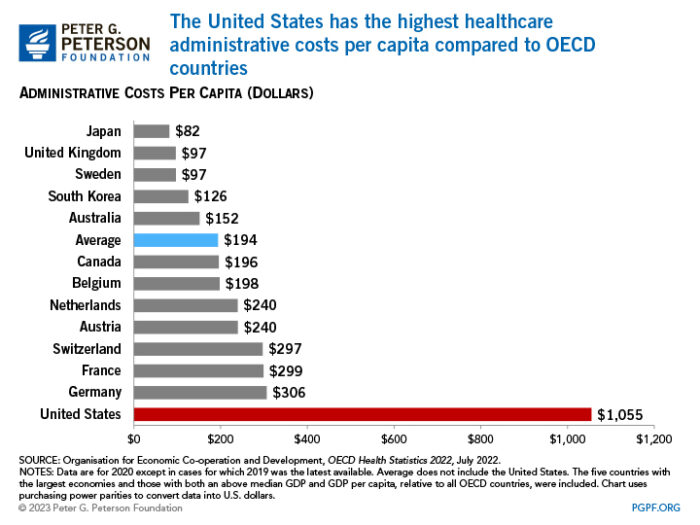

The United States has one of the most expensive health systems in the world, hampering the country’s fiscal and economic well-being. In 2021, U.S. healthcare spending totaled $4.3 trillion, which averages to about $12,900 per person. By comparison, the average cost of healthcare per person in other wealthy countries is less than one-half of that. What’s more, 34 percent of the nation’s healthcare spending is funded by the federal government — placing a strain on the federal budget and contributing to the nation’s growing national debt.

One commonly cited reason for the exorbitant cost of the U.S. health system is waste. Approximately 25 percent of healthcare spending in the United States is considered wasteful, and about one-fourth of that amount could be recovered through interventions that address such waste.

Reducing Medical Waste to Improve Equity in Care:

The longstanding problem of medical waste continues to bedevil our nation’s health care system. Although defined narrowly as “inefficient and wasteful spending,” medical waste encompasses a wide range of complex and interrelated issues: clinical inefficiencies, missed prevention opportunities, overuse, administrative waste, excessive prices, and fraud and abuse. The economic costs associated with medical waste are staggering, ranging from $760 billion to $935 billion, which accounts for approximately 25% of total US health care spending.1 Yet, the United States continues to rank last in life expectancy among high-income countries.

Medical waste affects every American. It is a major driver of rising health care costs, which, at an individual level, translates to increased premium contributions and out-of-pocket medical expenses. At a population level, medical waste crowds out resources that could be repurposed to support other high-value priorities. One obvious example is public health, which continues to be grossly underfunded; public health expenditures are projected to fall from 3.0% of total health expenditures to 2.4% by 2023.

On its own, medical waste warrants greater attention and action. However, within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, attacking and rooting out medical waste has become even more urgent. The pandemic is not a distraction but rather a painful reminder of the gross inequities that persist in this nation and the medical community’s failed attempts to eliminate them. Medical waste is a major contributor to health inequities, as measured by preventable illness, low-quality care, and reduced life expectancy in disadvantaged groups. New efforts to tackle medical waste should prioritize interventions that can mitigate such inequities.

Effective Medical Waste Management for Sustainable Green Healthcare:

This study examines the importance of medical waste management activities for developing a sustainable green healthcare environment. This study applied a multiple methodological approach as follows. A thorough review of the literature was performed to delineate the factors that have been explored for reducing medical waste; hospital staff who handle medical waste were surveyed to obtain their opinions on these factors; the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) was applied to determine the priorities among the identified key factors; and experts’ opinions were consulted to assess the actual applicability of the results derived by the AHP. The study identified the following factors as the most important: medical waste management (26.6%), operational management issues (21.7%), training for medical waste management procedures (17.8%), raising awareness (17.5%), and environmental assessment (16.4%). This study analyzed the contributing factors to the generation of medical waste based on the data collected from medical staff and the AHP for developing a sustainable green healthcare environment. The study results provide theoretical and practical implications for implementing effective medical waste management toward a sustainable green healthcare environment.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees