I act more like Uruguay’s President than the average American, environmentally, according to the NY Times

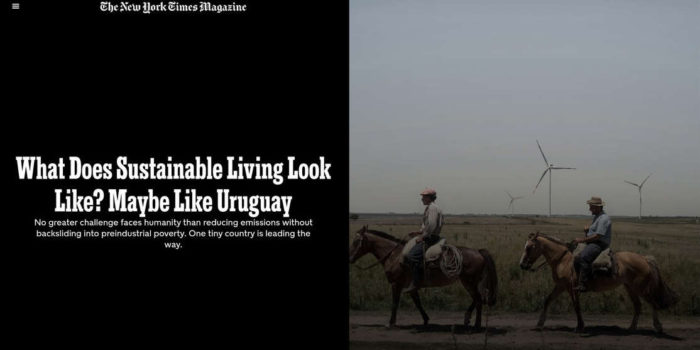

Several friends and readers pointed me to recent long article in the New York Times, What Does Sustainable Living Look Like? Maybe Like Uruguay by Noah Gallagher Shannon.

Does this paragraph describing and quoting the country’s president sound familiar?

[Uruguayan President José] Mujica harbored another deeper belief too. For years, he had been arguing that the “blind obsession to achieve growth with consumption” was the real cause of the linked energy and ecological crises. In speeches, he pushed his people to reject materialism and embrace Uruguay’s traditions of simplicity and humility. “The culture of the West is a lie,” he told me. “The engine is accumulation. But we can’t pretend that the whole world can embrace it. We would need two or three more planets.” He shared his own experience in solitary confinement, and how years without books or conversation drew him closer to the fundamentals of being: nature, love, family. “I learned to give value to little things in life. I kept some frogs as pets in prison and bathed them with my drinking water,” he told me. “The true revolution is a different culture: learning to live with less waste and more time to enjoy freedom.”

Unlike most Americans but like him, I prefer simplicity, humility, nature, love, family, and freedom to abandoning Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You, Leave It Better Than You Found It, and Live and Let Live. Just because America’s mainstream culture has abandoned the Golden Rule, Stewardship, and Common Decency doesn’t mean I will. I prefer living by these bedrock values, and personal responsibility, than the new (since I was a kid) American practices of capitulation, resignation, and abdication.

American Consumption and Waste

The article continues, describing a material culture based on durability instead of America’s increasing preference for disposability of things that don’t decompose:

Conspicuous displays of wealth seemed rare, as were the tiers of consumer goods that otherwise revealed someone’s spending. “There’s not the American consumerist mentality of ‘We need to get the next new thing,’” he said. On trips to New Orleans and Chicago, he had been transfixed by the selection of junk food in convenience stores, the undamaged furniture left on the street. “You guys throw away your whole home,” he told me. “Here, most of this stuff wouldn’t be trash.”

Look at what passes for progress in the U.S. today:

Independent modeling by Rhodium Group, a research firm in New York, estimated that the bill would cut emissions by between 32 and 42 percent by the end of 2030, compared to 2005.

Having dropped over 90 percent in under three years, 32 to 42 percent sounds like a low bar, and that’s compared to 2005, long after emissions grew. If we replace emissions with pollution from the extra mining for batteries, what have we gained? Why not return to simplicity, humility, nature, love, family, and freedom?

The Average American’s Pollution (prepare to vomit)

Enough about Uruguay. How about the average American’s pollution? The article documents our culture too and it’s insane. My consumption resembles virtually none of the following, yet I’ll contend I’m healthier, happier, and more productive, while helping people less fortunate than me more.

Let’s say you live in the typical American household. . . Since more than half of us live outside big cities, it’s probably in a middle-class suburb, like Fox Lake, north of Chicago. You picked it because it’s affordable and not a terrible commute to your job. Your house is about 2,200 square feet — a split-level ranch, perhaps. You’re in your mid-30s and just welcomed your first child. Together with your partner you make about $70,000 a year, some of which goes toward the 11,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity and 37,000 cubic feet of natural gas you use to heat the house, play video games and dry your clothes. You take six or seven plane flights a year, to visit your mom after her surgery or attend a conference, and drive about 25,000 miles, most of which you barely register anymore, as you listen to Joe Rogan or Bad Bunny. Maybe twice a month you stop at Target and pick up six or seven things: double-sided tape, an extra toothbrush, an inflatable mattress.

To me, this life sounds entitled and, if I don’t overstate myself, sad. Pollution hurts people and I wouldn’t want to hurt people so much.

The Root of the Problem: A Failure of Imagination

The article hits the core problem—a failure of imagination—in asking what most Americans couldn’t begin to answer: “How do we begin to imagine such a household?” I know the answer: practice by changing your life but Americans don’t want to.

This is the paradox at the heart of climate change: We’ve burned far too many fossil fuels to go on living as we have, but we’ve also never learned to live well without them. As the Yale economist Robert Mendelsohn puts it, the problem of the future is how to create a 19th-century carbon footprint without backsliding into a 19th-century standard of living. No model exists for creating such a world, which is partly why paralysis has set in at so many levels. The greatest crisis in human history may require imagining ways of living — not just of energy production but of daily habit — that we have never seen before. How do we begin to imagine such a household?

I know how to imagine it because I made it happen in my life, as anyone can, though they’re usually much better at falsely rationalizing and justifying why they can’t. When they finally commit, they’ll find it brings joy, fun, freedom, community, and things they value.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees