“Josh, You Can Grieve Your Loss Too”

I’ve posted about my September 11, 2001:

We called the company I co-founded Submedia. We filed the patent in 1998. Our first investment came in 1999, enabling us to pay ourselves salaries and hire people to develop prototypes and create partnerships with subway systems. Atlanta’s system signed first, followed by the PATH system connecting New York City and New Jersey. Coca-Cola signed in 2001 as our debut advertiser, beating Nike by an hour in the bidding. These were blue-chip advertisers and demand was high.

I had started taking tentative steps toward living the lifestyle of a successful businessman. I bought new, higher quality clothes and furniture, flew to California to visit national parks with friends and Miami for parties. I ate at more at fancier restaurants, looking for the latest openings. My apartment started to fill with stuff. I dreamed that when Submedia had a “liquidity event”—that is, my shares became cash—I’d fly my friends to celebrate in Europe.

For the launch, we hired a major New York public relations firm to use the near-magic appeal of our new medium to elevate the Atlanta launch into a global media event. Coke knows publicity as well as anyone and was fully on board. For the date, since Coke was advertising its Dasani water brand, they wanted a time in the hot summer, but after vacations so toward the end. Marketing people determined that Tuesdays were the best day for media coverage.

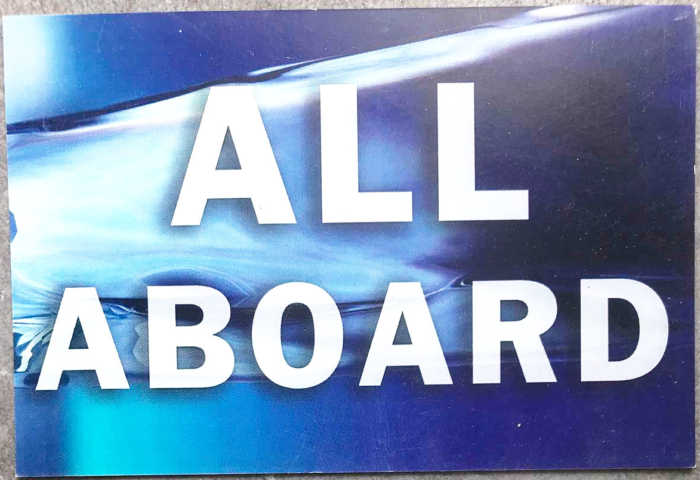

By launch, we had been covered in the Wall Street Journal twice, including a four-column spread, among other publications. The New York Times and live television coverage on all networks was scheduled. Expecting widespread coverage, we mailed postcards to invite our stakeholders. Here’s the front, featuring text over a frame of the Dasani ad of water flowing:

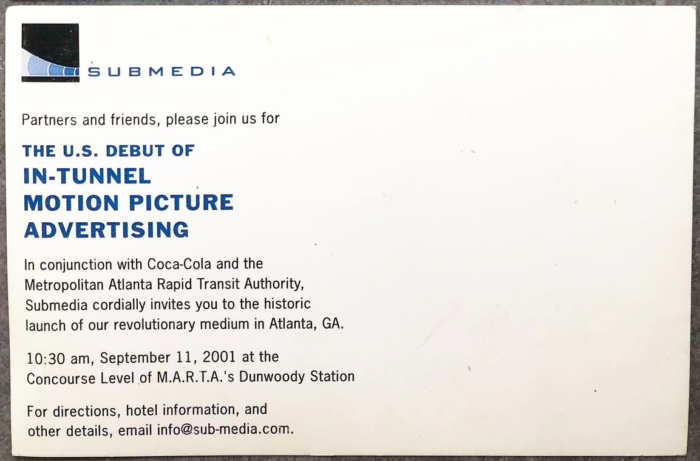

Here’s a picture of the other side of the postcard, showing our planned launch date, picked by experts for maximum publicity:

Yes, we planned to launch September 11, 2001.

I had spent the night before in the tunnels with the work crew on finishing touches and making sure everything worked and was safe. Everything checked out. We had prepared everything we could. Except for 9/11.

We didn’t launch that day. Since I owned about a third of the company then, my net worth at 8am on September 11, 2001 was about ten million dollars, on paper. By noon it was nearly zero.

Submedia launched in a subdued event in October, but the advertising market had collapsed. Subway systems denied access to build new displays. Investment dried up. I had made mistakes as CEO, as did the team, but the technology worked and we delivered what we promised to advertisers and subway systems. We had grown our staff fast, anticipating growth like the previous half-decade, so had to lay off people who had done great work. Doing so brought me to tears. I felt survivor’s guilt for staying. Some people who remained who had worked together rolled up their sleeves to salvage what we could, but others split into factions, trying to get they could. Board members screamed at each other.

It was my first time as CEO. I confused authority with leadership. I didn’t know how to unite and motivate a team under adversity. Soon enough, the investors gained financial leverage to squeeze me out and did. Even then, I felt shame and guilt for being unable to repay shareholders who had invested in a dream I sold them so I kept coming to the office to try to help. I didn’t eat enough; my well-being seemed irrelevant and distracting.

I had lost all I cared about. To start the venture I had abandoned my dream of following in the footsteps of Galileo and Einstein. In the end, without ownership of my invention, all I had were a few connections in a field with values that conflicted with mine. Outdoor advertising mostly charges rents for spaces often blocking views of nature, promoting sugar water to kids.

Meanwhile, across the street from my apartment is a firehouse that today has a plaque commemorating the men who saw the flames on 9/11, entered the towers to save lives, and never came back out. One of my oldest friends, later the co-founder of my second company, served in the first Gulf War as a Marine. He had enlisted to defend his country and freedom, willing to risk his life, as did many after 9/11. All of these people who lost or risked losing more had families. How could I compare my loss of mere money on paper and intangible dreams with their losses? So I didn’t complain. Only decades later, when I started sharing this story, did friends point out that because others lost more didn’t mean I couldn’t grieve my losses.

Instead, for decades I didn’t allow myself to grieve my losses. For years, I saw little to live for, nor any foothold for traction, nor anyone to share my despair with. I don’t know how seriously I considered taking my life, but it seemed a rational alternative to the hopelessness, helplessness, guilt, and shame I saw no way out of. I couldn’t talk about it because I didn’t want to be put on suicide watch and my problems seemed small compared to 9/11 and a global recession. Even so, I couldn’t do it for two overarching reasons, First, because I knew somewhere inside that life was glorious and beautiful to give up on. In college I helped a friend who shared with me that he had been preparing to take his life. I put him in touch with a professional who told me that survivors look back at their most stressful times as temporary; they just couldn’t see in the moment. Second, because people loved me and I loved them. How could I give up on them? Maybe I had some faith in myself too.

I wanted to curl up and escape from the world. But I was two years into ten-year mortgage. Graduate school paid a stipend so I had little other debt. I chose to accept only enough salary in cash from Submedia to live on, keeping the rest in the company. The investors squeezed me out of it, so I had no savings either. Whatever my emotional state, I had to look past myself and the present moment. I had to get a job, meaning I had to find people I could help so they could help me back with a paycheck, as well as to find meaning, purpose, community, and life again.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees