The Ruling Race: Quotes on those who improve their lives on the suffering of others, corrupting them

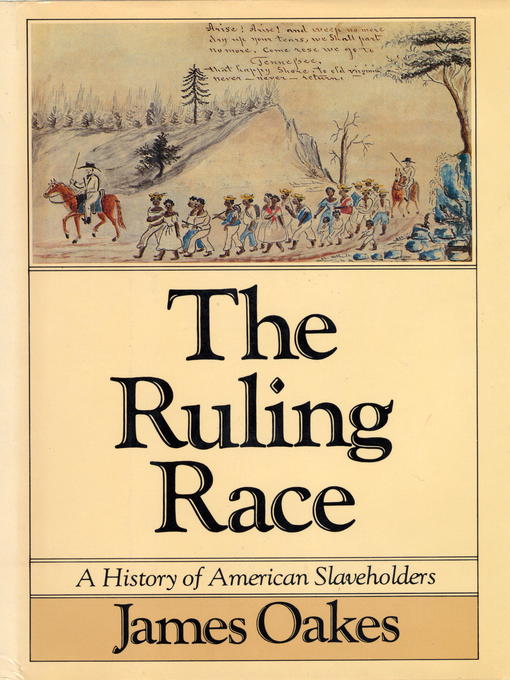

Podcast guest James Oakes’s book The Ruling Race describes the demographics, beliefs, and views of slaveholders in the U.S. south. They are no more or less human than you. The book reveals how being on the dominant side of a dominance hierarchy corrupts one’s values.

Following the What is Politics? podcast by podcast guest Daniel, I’ve learned that dominance hierarchies emerge when two conditions apply: one person or group can control access to a needed resource and others have no alternative. When you see a hierarchy giving one group dominance over another, look for the necessary resource that group can control to and how the group subjugated lacks alternatives. Want to remove the hierarchy? Work on that control and lack of alternatives.

Today, I see people and communities with more access and control of a) fossil fuels exerting dominance over others, whose ability to escape that dominance disappeared when we overpopulated the planet. They also control access to b) violence and deadly force as well as c) financial markets that control flow of information. Nearly no one can live off the land any more, as our culture has invaded all that can sustain a community. People who used to live there have to join our society, at the lowest status level, sadly.

Hence we live in a global dominance hierarchy that will tighten as fossil fuel or any energy source supplies decline, population increases, and alternative sources of food and other supplies decline. That is, unless we change our culture both to require less fossil fuels or any source of energy and to bring our population to sustainable levels, which is my main mission.

In the meantime, how different are people who control access to fossil fuels, violence, and financial markets today than slaveholders then, which, compared to most people alive today, includes most people reading these words? How easily can you read ourselves as polluters into the parts of slaveholders then?

Inner conflict, p. 109: “Masters who had little trouble rationalizing the compatibility of slavery with their patriotic ideals found it hard to be a Christian and a slaveholder at the same time. A North Carolina master warned his children that “To manage negroes without the exercise of too much passion, is next to an impossibility, after our strongest endeavors to the contrary; I have found it so. I would therefore put you on your guard, lest their provocations should on some occasions transport you beyond the limits of decency and Christian morality.” A Virginia master echoed these sentiments. “This, sir, is a Christian community,” he wrote in 1832. “Southerners read in their Bibles, ‘Do unto all men as you would have them do unto you’; and this golden rule and slavery are hard to reconcile.”

More inner conflict, a slave owner lamenting how bad she felt, p. 115: “Many masters never forgot the antislavery messages which suggested to, as one southern preacher flatly declared, “no slaveholder could be saved in heaven.” The disappearance of such lessons was an indication of the intensification, not resolution, of the dilemma of slaveholding. “Always I felt the moral guilt of it,” a Louisiana mistress admitted, “felt how impossible it must be for an owner of slaves to win his way to heaven.” Ann Meade Page of Virginia prayed for deliverance from the moral burden of slaveholding. “Oh my Father, from the distressing task of regulating the conduct of my fellow-creatures in bondage, I turn and rest my weary shoulder on thy parental bosom. . . . My soul hath felt the awful weight of sin, so as to despair in agony—so as to desire that I had never had being. Oh God! then—than I felt the importance of a mediator, not only to intercede but to suffer under the burden of my guilt.”

Rationalizing and justifying what they believed was wrong, if only he could stop from owning slaved but he can’t help it, p. 119: “After a great deal of contemplation and reading, [Jeremiah] Jeter finally concluded that while slavery was neither “right . . . [nor] the most desirable condition of society,” it was at least “allowable” under the laws of God. David Benedict underwent a similar transformation. He arrived in Charleston in 1776 with “every prejudice I could have against slavery,” only to find his principles impractical. “Providence has cast my lot where slavery is introduced and practiced, under the sanction of the laws of the country,” he wrote some years later. “Servants I want; it is lawful for me to have them; but hired ones I cannot obtain, and therefore I have purchased some: I use them as servants; I feed them, clothe them, instruct them, &c.—I cannot do as I would, I do as I can.”

No context to raise children, p. 118: “a Virginia master thought the South was “a bad country in which to bring up boys. I wish mine could be raised in the indigence and simplicity that you and I were,” he wrote a northern friend. “You may feel very happy that you are not in a slave state with your fine Boys, for it is a wretched country to destroy the morals of youth.”

They knew a bloodbath was coming, p. 120: “In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, slaveholders occasionally revealed their discomfort by explicitly refusing to talk about slavery. In 1807, a Louisiana master was “fearful that unless a stop is soon put to the increasing number” of blacks imported to America, a bloodbath would ensue. “Much more might be said on the subject,” he wrote, “but I must drop the curtain for the present.” With respect to slavery, George Washington admitted, “I shall frankly declare to you that I do not like even to think, mush less talk, of it.”

Ideals corrupted by owning slaves, by “convenience”, p. 121: “Henry Watson, Jr., of Alabama, would reduce the moral dilemma of the slaveholders to the pathetic proportions of an epigram. “I abominate slavery,” he had written in 1835, shortly after moving to the South. But within fifteen years, Watson had repudiated his youthful ideals. “If we do commit a sin owning slaves,” he wrote his wife, “it is certainly one which is attended with great conveniences.”

Using racism to defend slavery, comparing blacks to baboons, p. 133: “Samuel Bass, a carpenter hired to build a new home for a Louisiana slaveholder, Edwin Epps, provoked his employer into defending what Epps probably never thought to defend. “What right have you to your niggers when you come down on the point?” Bass asked. “What right!” the slaveholder shot back, “why I bought ’em, and paid for ’em.” For the free-thinking carpenter that answer would not do. “Of course you did,” Bass conceded, “the law says you have the right to hold a nigger, but . . . suppose they’d pass a law taking away your liberty and making you a slave?” Epps scoffed at the idea. “Hope you don’t compare me to a nigger, Bass.” The carpenter remained unconvinced. “In the sight of God,” he asked, “what is the difference between a white man and a black one?” All the difference in the world, the slaveholder answered. “You might as well ask the difference between a white man and a baboon.”

Freedom requires slavery, they conclude, p. 141: “The racist subjugation of blacks helped open the way to universal white manhood suffrage by silencing a potentially rebellious underclass of black workers. “In this country alone does perfect equality of civil and social privilege exist among the white population, and it exists solely because we have black slaves,” the Richmond Enquirer declared. “Freedom is not possible without slavery.””

Blacks aren’t human, they conclude, p. 143: “Most slaveholders had long rationalized their devotion to slavery and freedom in the same way that Northerners justified their own discriminatory practices against blacks. When asked if all men were “free and equal as the Declaration of Independence holds they are,” a Louisiana slaveholder answered confidently: “Yes, But all men, niggers, and monkeys aint.”

Do these passages illuminate us in our time for you as much as they do for me? I’ll pause for time now. More to come.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees

Pingback: If transported to 1850, would you rather be an abolitionist with little hope of success or a slave owner with comfort and convenience? » Joshua Spodek

Pingback: Proslavery Thought in the Old South (1935) quotes, by William Sumner Jenkins » Joshua Spodek