The text from episode 630: Simplifying Meditation Words and Meaning

The notes I read episode 630: Simplifying Meditation Words and Meaning from were long, so instead of including them in the podcast notes, I’m posting them separately here.

Longtime listeners know I meditate regularly, now 25 minutes every other day. I started in 2007 with a ten-day vipassana retreat and have done a few ten-days, plus some 5-days and 3-days. Mostly I pay attention to my breath or do body scans. I don’t usually do guided meditations, but listen to the Sam Harris podcast so joined his Waking Up app.

By now, I’ve listened to nearly all the recordings in it, including the guided meditations, his conversations with guests on theory and practice, and most guests’ recordings.

I love many parts and find them useful, but find some difficult following some things he says no matter how many times he says them, no matter how common they are in meditation circles. Terms like “mindfulness” and “nondual” sound vague. Phrases like “arising and passing away” and “identifying with the thought” sound mystical despite his saying we have no free will. If our minds are mechanistic, why so vague? It’s nice to know anger will pass, but what’s the mechanism? He talks about “nature of mind,” which implies a mechanism.

I decided to explain a bunch of these vague parts that I found confusing in the way that I would have found useful years ago. I suspect many of his listeners are analytical and would benefit from less vagueness. I hope my explanations ease their practice, though nothing substitutes for practice.

I’ll start with an example from life. A couple weeks ago I was riding my bike upstate New York on a road I thought I’d never been on before. Suddenly I noticed to my left a field I had been in before. The summer before, my then girlfriend and I had hiked through it. I’d noticed an apple tree on the hike in that field and we picked some ripe apples and ate them. I had only been there once. The odds of my passing by on a random bike ride were low so I would never expect to pass a place I’d been, but seeing it, I couldn’t help but connect it. I got off my bike, and walked through the field to find the apple tree, thinking of my ex-girlfriend.

What happened? A year ago, my mind connected the patterns of the field with the reward of the apple and bonding with someone I cared about and stored them in my memory. Our ancestors’ minds from long before human or mammal have been doing it. The patterns “like food” and “like relationship” led me to stay and search. A pattern like “burned hand on stove” would lead me to avoid. “Stubbed toe walking in dark” leads me to walk slower when I go to the bathroom at night.

Let’s look at this process from a different view. Some cells in my body create fingernails. Some create hair. No matter how many times I shave or clip, they keep producing. I don’t ask them to. I couldn’t stop them if I tried. Like those cells producing what they produce, in my mind are parts that produce thoughts, emotions, and motivations. Your senses and existing thoughts are constantly producing new input and unique combinations. When input matches some stored pattern, those pattern-matching cells in your brain prompt thoughts, emotions, and motivations relevant to the input, though they may not seem relevant to the rest of you.

Thoughts and emotions may seem random, but if you look carefully, you’ll see that many of them are prompted by input from senses or other thoughts, maybe all, as I suspect. New thoughts and emotions from new sensory input and other thoughts and emotions cause those cells to override the old ones. This is the mechanism behind “thoughts arising and passing away.” It’s not mystical or random. It’s roughly speaking deterministic, but too complex to predict in practice, but the more you look at your thoughts, the more you’ll find thoughts less Just “arising” and more responding to input where you can see the cause.

I’ll introduce another view to explain mindfulness and related concepts.

If you drive an internal combustion engine car with a standard transmission, you know that the engine runs all the time, even when the car isn’t moving. If the gears between the engine and wheels were permanently connected, the wheels stopping would cause the engine to stop and you’d have to restart it every time, which would break the engine. Instead, it has a clutch, which you operate with your left foot, which disconnects the engine from the wheels so the engine can idle—that is, spin, ready to drive the car when you reconnect it.

An automatic transmission doesn’t have a pedal for your left foot. Instead of a clutch it has something called a torque converter, which automatically tries to connect the engine to the wheels. If you take your foot off the brake on level ground, the torque converter in a car with an automatic transmission will start the car moving even if you don’t press on the gas. The faster it goes, the more it connects the gears until the car moves along.

All those thoughts your mind is creating are like the engine in a car. An untrained mind is like a car with an automatic transmission. Each thought tries to engage the wheels. Once the car starts moving, you have to pay attention to where you’re going. When the car is moving and you have to pay attention to driving is “identifying with thoughts.”

Developing mindfulness is like developing a clutch so you can disconnect the engine—the thought-producing parts of your mind—from the car—the rest of your mind and body. It enables you to look at the engine running without the car moving around forcing you to drive. A clutch gives you greater freedom when you want it and control when you want it.

Just knowing you can develop that clutch—that’s “mindfulness”—and skills to use it—that is, pay attention to your thoughts without them carrying you away—doesn’t mean you have those skills. Like all skills, they come through practice. That’s why practicing meditation gives you freedom and control. It’s like a race car driver developing clutch skills and learning more about the engine, which enables him or her to drive better. Some thoughts engage your mind subtly, faster, or more strongly so are harder to catch before sweeping you up. Still, no matter how long you’ve meditated and how much skill you develop, some thoughts will engage you. When you notice yourself engaged in thoughts while meditating, you can return to your breath. That training is useful in life, like if you get in an argument and lose your cool, you can choose to disengage.

You don’t have to engage the clutch. Sometimes you want to let emotions engage without you paying attention. On a roller coaster or during sex, for example, you just want to enjoy the ride. But when stressed, it can be useful to engage the clutch and look at the engine. Why is it making me sweat, focus so intently I lose perspective, and so on? Curiosity about the engine—your mind—can occupy your mind and lead it and your body in a new, calmer direction.

You might ask in this clutch/torque converter analogy, who or what is the driver? At first you might think it’s something like your soul. Sam likes big words sometimes and uses the term humunculus, which just means little person. After noticing that no “driver” controls your hair or nails growing, or your liver. With mindfulness practice—that is, if you watch your mind enough—you realize your thoughts and emotions happen without a driver too. You don’t pick them. The pattern-matching responding to sensory input plus other thoughts prompt them. Later you see that your choices don’t happen because of a driver. They happen in the engine, as much on their own as your nails and hair growing. You feel like you consciously chooses things, but you don’t. Something inside you unconsciously chooses things, which your consciousness observes. After some part of your mind chooses, another part creates a thought “that’s why I chose that way.” Your consciousness didn’t produce that afterthought either. It just observed it. That’s what Sam means by “the self is an illusion.” I think of it more as: “my consciousness didn’t even think the thought, ‘I thought that.’ Even that thought, cells in my body created, as much as other cells create fingernails, which I didn’t choose either.”

It turns out the whole car runs on its own. Nothing requires a driver. Consciousness doesn’t do anything. Everything happens in the engine—that is by cells and organs. All the driver does—all consciousness does—is observe the engine and car—your mind and body—running on their own.

You may know Jonathan Haidt’s pair of analogies illustrating emotions and intellect. He says most people think of emotions as causing our behavior and intellect guiding it, like a charioteer guiding horses. The horses run and the charioteer directs them. He says it’s more like a rider on an elephant. Elephants are smarter than horses, so choose more, and bigger, so listen less to the rider. In this analogy, the rider kind of guides the elephant, but it mostly goes on its own with the rider thinking he or she is choosing, but more after-the-choice thinking “that’s what I meant to do” and rationalizing a choice he or she didn’t make.

What happens in your mind is a step further. The rider guides nothing. It just observes. It doesn’t even create the thought “that’s what I meant to do.” The engine does. Consciousness observes it too, getting carried away with it. But if you look closely, you can clutch and disengage from that thought too and just observe it.

That’s consciousness. Nobody knows why or how it works or how it came to exist since as far as anyone can tell, your body works without it. Nobody can measure anything about it except you know your own. In that mysterious way, something you can’t measure or show anyone else, what we call entirely subjective, is in your personal experience, the only objective thing that exists, your awareness. Everything else you can imagine can be fooled.

I’ll explain another concept here. When you realize all your thoughts occur automatically from the rest of the world influencing it through your sensory input, you may stop seeing your mind as separate from everything else. It’s part of one big whole. That’s what “nondual” means, that your mind isn’t reacting like something separate so much as flowing with everything else. I use the term “harmony” more than “nondual,” which I think reflects influence from the Taoist book Tao Te Ching.

I hope these analogies clarify these terms that for me would be vague otherwise. Obviously, analogies aren’t perfect, but they would have helped me if I’d heard them earlier. Also, knowing you can have skills isn’t having them, any more than knowing you can play the piano enables you to play. Like all skills, you have to practice. Like all skills, the more you practice, the greater your skills. With mastery comes facility, freedom, self-awareness, greater self-expression, and usually ability to share what you’ve learned with others, which creates community and greater learning and understanding.

During an Ask Me Anything, a listener asked Sam for advice since he or she couldn’t stop breathing voluntarily when trying to pay attention to their breath. I think Sam missed a great opportunity to help someone out of their confusion by giving them something to notice, like in basketball if someone dribbles poorly, you give them dribbling exercises. In this case, if the person couldn’t help breathing, it wasn’t voluntary, yet they perceived it as voluntary. I would suggest looking more at the perceived choice to breathe. I think if that person looks more closely, they’ll see that they aren’t consciously choosing, but rather perceive the choice made, then perceive thoughts that they made it, but those thoughts also arose automatically. Seeing that choice made and seeing the follow-up thoughts happening can reveal how all choices work and how feeling like you’ve chosen because of those follow-up thoughts works too. When you see it, you’ll feel liberation. When you see that it happens that way for everyone else, you’ll develop compassion, empathy, patience, and see how to lead others and yourself.

I think it’s worth repeating that learning you can clutch and clutching when and how you want, or letting the engine and car cruise when you want, creates incredible freedom and control. Sam points out how some meditation advocates point out results from the simple act of meditating: maybe they’ll cite results that it calms you, relaxes you, lowers your blood pressure, makes you feel more love and kindness. Those results are great, he points out, but the ability to observe your engine and improve how you use it—that is, mindfulness—gives you options to do what you want, not to be caught up in driving; or to choose how and where you drive. It gives you freedom. You don’t get caught up by things you don’t want to be, like arguments, politicians trying to make you fearful, or addictions telling you you are powerless.

You may be thinking, “if I can’t control anything, just observe, what difference does it make?” You hearing these words, if they affect you how they’d affect me, will lead you to meditate differently, probably more and more effectively, outside your control, just within your observation. I’m doing it because of what influenced me, which implies a chain of causation going back to, well I don’t know how everything got started, so consciousness and evolution, maybe even cosmology seem connected. Did consciousness emerge from complexity, like an anthill emerges from a minimum number of ants and amount of sand, or was it already there? Not only does nobody know how consciousness came to be or why, but in my opinion, nobody has made any progress on answering the question. That question is the Hard Problem of Consciousness. Mostly I don’t bother asking, but it comes up when paying attention during meditation. All I know is I have consciousness.

Mindfulness is only part of what I consider a full gamut of personal leadership. Some low-level basics include the three pillars of a healthy diet, daily vigorous exercise, and the right amount of sleep for you every night. I consider the ability to create new beliefs as important. It seems just as mystical until you get it, then it seems essential and you feel compassion or even pity for those who don’t get it. You can learn to create new beliefs for how you see the world. Sam calls it framing, but I haven’t heard him develop it nearly enough. As best I can tell, he doesn’t see you can learn to practice it as easily and accurately as any other skill. My leadership book teaches it. It’s one of Viktor Frankl main messages in Man’s Search for Meaning, where his framing allowed him to experience love and bliss in Auschwitz, where he was imprisoned and tortured. He was just a regular human. If he can create beliefs that make Auschwitz something meaningful, then we can do it with our situations, which are likely less challenging.

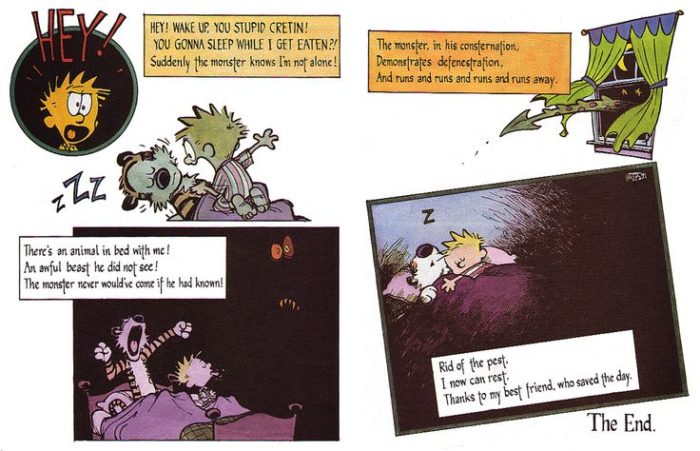

Now for a comic interlude and a drinking game for listening to Sam. Speaking of big words, if you like his using “defenestrate,” look up Calvin and Hobbes using the term. I consider the time Bill Waterson used the word “defenestration” one of the best strips of one of the best comics.

Here’s the drinking game. I don’t know about you, but outside of Sam’s recordings, I almost never hear the phrase “in some sense” but I hear it in every episode, sometimes from him, sometimes from guests, usually a few times in an episode, sometimes many, sometimes in variations like “in a very real sense” and so on. If you like the book Elements of Style by Strunk and White, you may recognize it as a qualifier like pretty, quite, very, or somewhat but for people who want to make themselves sound smart. As you’ve probably guessed, the drinking game is to drink when Sam or a guest says it. If this recording counts, I said it twice. Maybe some day he’ll bring me on as a guest and I’ll say it, but I’ll try to avoid it because I find it annoying. Just say what you mean without the qualifier. Now, like me, you won’t be able to miss it.

Since Sam often lists the environment as one of the top issues of our time and I work on sustainability leadership, I have to comment that on the environment, Sam deeply misunderstands systems and so thinks things will reduce pollution that will in practice increase it. He keeps citing Elon Musk as someone helping the environment. Elon Musk is today’s Robert Moses. For those not familiar with the Cross Bronx Expressway, Moses was New York’s city planner who kept building roads he thought would alleviate congestion from the last road he built, which he thought would meet demand. He didn’t realize new roads induced demand, a systemic effect.

When James Watt invented his steam engine, it was more efficient than ones before. People predicted coal use would go down. It went up. For each use it dropped, so more people found more uses for more steam engines, which increased coal use. The place to look is not individual uses, like comparing one electric car to one gas car, but on the demand curve for what new uses innovators will find. Uber was predicted to lower congestion and miles driven but increased both. LEDs are leading to lighting things that never needed lighting and will likely overtake incandescent pollution. They have on light pollution. One helicopter drone pollutes less than one helicopter, but there are tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands by now, likely overall polluting more than all helicopters used to.

If you know the terms “rebound effect” or “Jevon’s paradox,” you’ve heard how economists think of the effect, but they aren’t odd side-effects or paradoxes. When you understand them, you see they are how the system works. Technology doesn’t have a value. It’s a tool that amplifies the values of the user and system. You can tell a system’s values by its results. Our system values growth at the cost of pollution. Musk’s strategy is to sell more cars, which he wants to be electric. A sustainable strategy would be to sell fewer cars with a tactic of making the ones we can’t obviate the need for electric. Musk made the tactic a strategy. That tactic can work within a sustainable strategy, but no amount of unsustainable strategy can be made sustainable.

How to need fewer cars? Redesign cities in the way Amsterdam did from when it was flooded with cars and Cross Bronx-like highways were proposed, including tearing down Amsterdam’s core you’ve visited if you’ve visited Amsterdam. Their designs are spreading and people prefer them. American cities like Houston went the opposite direction, but could follow Amsterdam, even now.

Sam sounds like he speaks to Silicon Valley types who promote technology without understanding systems, as modern-day James Watts. If you look at what nuclear and fusion, if it ever happens, do, they accelerate the system. They already require fossil fuels to build and operate, but even if they didn’t, they would accelerate all the pollution everywhere else in the system, accelerating our problems. CO2 is only one problem. Even if they only produced heat, which physics says you can’t avoid, exponential growth means that heat will keep growing. I’ll link to a recent paper in Science that quantifies it, but roughly, if you bring what generates power in the sun into our atmosphere, sure, we’ll get work from it, but we’ll get heat too. We can’t dissipate that heat. That’s global warming. We’ll cook ourselves faster, in the order of a few human lifetimes at modest growth.

If you say, we can stop growing, then there’s our solution. If we can stop growing in the future, we should stop growing now. If we can’t now, it will be harder and involve more suffering then.

Sam has said to guests that people in the past had less technology, but were just as happy, and concluded that we can too compared to a future with more technology, so we don’t need more technology. It’s nice to think we’ll keep reducing some kinds of pain, but he knows that technology will never end suffering.

Solutions that work regarding cars are city planning, as in Not Just Bikes, one of my favorite video channels (and I’ve had the host on my podcast). Solutions in technology are like Low Tech Magazine, one of my favorite sites on the internet. Its tagline, “we love technology,” shows you can love technology but not pollution and always progress without harm. The solution is not polluting a little bit less, which is to say not changing the system, but to stop polluting.

In an informal study, I went to a supermarket to observe the items in at least 100 shoppers’ carts at the checkout. Every single item in every cart was packaged. Even fresh produce was put in plastic bags (on top of the stickers the suppliers put on each piece). I’m sure some shoppers buy produce without putting it in plastic bags, but all the ones I saw did.

We have created a culture where the absolute basics of life require hurting other people. It bears repeating: We have created a culture where the absolute basics of life require hurting other people.

Think about it: if simply living requires hurting other people, if every day 330 million Americans and billions of people around the world, simply to live, must pollute several times a day, what amount of pollution per person won’t lower Earth’s ability to sustain life? Remember, plastic pollution poisons for at least five centuries, on top of the people (and wildlife) displaced or killed in the extraction, polluting in making, and the other poisonous chemicals created and released in the process.

I think you have to conclude that if we pollute with every meal (and increasingly in every sip of liquid), no amount of pollution can work. The only amount of pollution that can allow Earth to sustain human life in the long term is zero, as best I can tell. Not a little bit less than usual, nor a lot less: Zero, how humans lived for hundreds of thousands of years. It’s tempting to say, “but they were diseased, miserable, and were lucky to live past 30,” but that’s the addiction speaking. History and anthropology show we evolved to live modal lifetime of 72 years. 30 being old age was a short blip on an evolutionary time scale caused not by nature but by human society.

I’ve been asking people since my informal study if they can imagine a world without pollution. Almost none can. With so many people today unable to imagine a world without pollution that actually existed—the world that nearly all our ancestors inhabited for hundreds of thousands of years with no pollution yet they thrived enough to populate the planet without even the wheel—I’ve come to describe our unsustainable culture as a failure of imagination and a failure of leadership. Of those who can imagine a world without pollution, many can only imagine it a Mad Max-type dystopia after civilization has broken down.

Suggest polluting less to someone whose vision of no pollution is a hellish dystopia and they will hear you suggesting making life worse. They will resist based on their false beliefs from addiction to what pollution brings. Using CCCSC will reinforce those beliefs. Addiction leads them to believe less pollution means reverting to the Stone Age, mothers and children dying in childbirth, thirty being old age, every cut resulting in infection and death.

Sam knows it’s difficult to dislodge a culture based on an idea like free will. People refuse to see or consider otherwise. Likewise, a culture that sees nature as dangerous and we need technology to pacify it is hard to displace, but homo sapiens lived for 300,000 years without the wheel and still populated the globe. What more do we need to see that nature is abundant, safe, and healthy. We created stories saying otherwise to justify and rationalize civilization destroying it, in a similar process to how we created racism to justify slavery, which is not my idea. I’ll link to historian Eric Eustace Williams’s book describing it).

In contradiction to technology promoters’ belief that we must work hard and fast to escape nature’s danger, there exists the sloth—an animal so opposite to working hard nonstop that we call it the sloth. It turns out that modern species of sloth diverged into their branches tens of millions of years ago. About ten thousand years ago, when humans reached their territories, their populations decreased with some species going extinct. In some cases, it seems that nature nurtures while human culture is dangerous. At least we can say we don’t have to push on the gas when we have a safe, supportive evolutionary niche. If we want to progress, humans are plenty ingenious without fossil fuels.

I’m not saying no to technology. The exact opposite. I favor technology in a system or culture with values of Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You, Leave It Better Then I Found It or Live and Let Live, which, regarding how we affect each other through the environment, our culture has abandoned.

Let me qualify that outside environmental interactions, we often espouse those values. Many individuals still do regarding environmental interactions, as do some organizations, but our culture overall has abandoned Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You, Leave It Better Then I Found It or Live and Let Live.

One of Sam’s favorite topics—psychedelics—can also reveal another huge value to preserving wildlife and nature beyond the tech optimism he’s been sold on.

On my podcast and sustainability leadership training, I ask people what the environment means to them, to describe their personal experience of nature. Nearly everyone’s first answer is about the disasters, catastrophes, and predictions of more they learn about from the news, but that’s not their experience. That’s their reading and watching about something else. When I guide them to their actual experiences, they quickly find personal experiences that are deeply meaningful, often in their childhood, but even if decades ago, meaningful until today. The experiences might be one-time events like seeing a particular sunset or the Grand Canyon for the first time. More often they are multiple-time events, like regular visits to forests, picking apples with their grandmother to bake pies with every fall, or spending time on the beach. Usually they’re in solitude, but sometimes with people.

When I ask them to name emotions they feel in such times, they often describe oneness, connection with everything, humility, their place in the universe, calm, wonder, awe, and emotions like them. They describe them as deeply valuable.

Sam had a guest, Roland Griffiths, I think, from Johns Hopkins, who studies psychedelics. He asked people who took mushrooms to describe their experiences. Roland was impressed with how positive and valuable people described the experiences, often as one of their top experiences, on par with having a child. Their descriptions are remarkably similar to people’s experiences of nature. On the one hand, they’ll experience things more intensely on mushrooms, but experiences in nature can happen all the time, involve no risk or side effects, cost nothing, and can give as much value.

Why don’t we value experiences in nature as much? Why doesn’t Sam?

Until possibly living memory, nearly everyone lived within walking distance of solitude in nature, maybe walking among trees, watching waves lap on the shore, hearing birds and frogs, or whatever wildlife was around, not hearing any noise of honking (believe it or not, a car honked as I typed that word) tires on pavement, speakers blaring, and so on. As valuable as trees lining sidewalks and river fronts in cities, they aren’t wild nature. They don’t give the mental and physical results that nature does. We’ve told ourselves that nature is dangerous and we need to tame or overcome it, ignoring that our ancestors lived as homo sapiens for 300,000 years, populating the planet, showing it’s abundant and safe, despite the fears we, in ignorance, have taught ourselves, perhaps to justify paving it over.

We don’t know what we’re missing. Psychedelics are like a remedial jolt to restore what used to come automatically to everyone. I suggest that most of the benefits Sam sees in psychedelics, for example that you can’t miss that something will happen, are not only available in and from nature, they were automatic for most of our species’ existence. Again, we don’t know what we’re missing so we think amusement parks or even national parks that are often effectively curated experiences remotely resemble solitude in nature. Even much of meditation’s value comes automatically spending time in nature. You can’t help contemplate. You don’t get it driving through, at a tourist destination filled with people, or where cars on roads make more noise than the flora and fauna or just wind.

I don’t know details about Sam’s time in Tibet or wherever, but I know he refers to going in nature on psychedelics. I suspect he’d agree on the value of restoring and rewilding nature as a way to restore what meditation brings and that paving it over and reducing it contributes more than he thought to the problems of isolation, anger, reactivity without reflection he sees our culture growing.

He should be a guest on my podcast or invite me on his. He mostly invites authors and my next book, on sustainability leadership, isn’t out yet, but he and his audience would still benefit more than from many of his guests.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees