What’s special about 436?

While reading ProPublica’s story How a Grad Student Uncovered the Largest Known Slave Auction in the U.S., I came across these paragraphs about Lauren Davila finding a newspaper ad from 1835 announcing someone having sold 600 slaves in one auction:

A sale of 600 people would mark a grim new record—by far.

Until Davila’s discovery, the largest known slave auction in the U.S. was one that was held over two days in 1859 just outside Savannah, Georgia, roughly 100 miles down the Atlantic coast from Davila’s home. At a racetrack just outside the city, an indebted plantation heir sold hundreds of enslaved people. The horrors of that auction have been chronicled in books and articles, including The New York Times’ 1619 Project and “The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History.” Davila grabbed her copy of the latter to double-check the number of people auctioned then.

It was 436, far fewer than the 600 in the ad glowing on her computer screen.

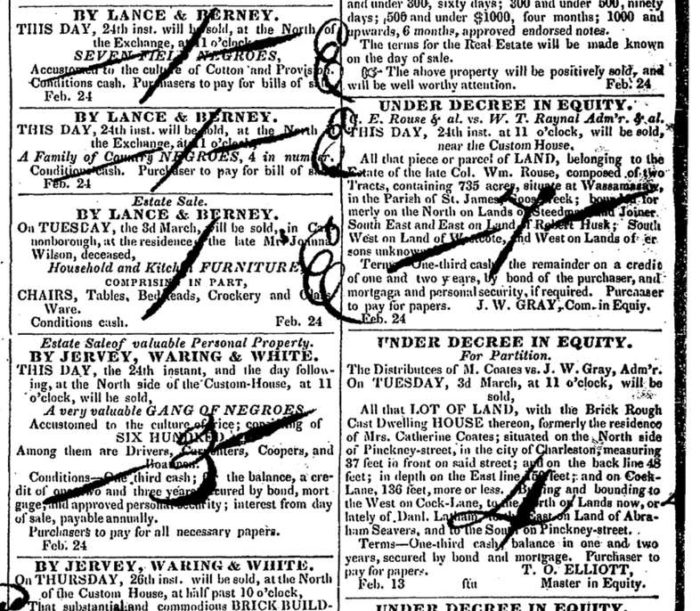

Here’s what she found, the ad in question is on the left:

Read the story for more history, detail, and reflection.

For my part, the number 436 stood out. In the story, it referred to the previous largest-known single sale. I had seen the number recently.

I recently read a story in Outside Magazine, Should I Stop Flying? It’s a Difficult Decision to Make., that struck me for how well it conveyed my experience when I struggled to avoid flying, before overcoming withdrawal. I invited the writer, Kate Siber, to record a podcast episode. She agreed. We recorded. It’s in the editing queue. It was an evocative conversation I’ll link to when I post it.

She wrote about the trend of people pledging to fly less:

The number of people pledging to stop flying grew so much that Swedish air travel declined 5 percent between 2018 and 2019, and the movement strengthened in other parts of Europe as well. In the U.S., the flight-free movement, in the form of groups like Flight Free USA and No Fly Climate Sci, has been slower to spread but is growing. This year, Flight Free USA, for example, is on track to see the largest number of pledges to stop or minimize flying at 436. By comparison, tens of thousands have pledged in Europe over the past four years.

There was that number 436. In our conversation, I remarked at how small it was for a nation of 330 million. Just over one in a million American’s chose not to fly with enough intent to publicize it with Flight Free USA (here’s my story there). Since an estimated 80 percent of people have never flown, many more Americans haven’t flown without pledging, maybe hundreds of millions.

Way to Go, USA: slaves sold versus deliberately not flying

Until Davila’s discovery, America tied the known number of slaves sold at once with the number of people pledging not to fly. Her discovery shows that America sold more slaves at once than committed not to fly. I know these domains are widely unrelated, but how can it not make you think?

At America’s peak, it was the largest slave empire in history, with about 4 million people enslaved. To compare, air pollution alone kills 9 million people annually, among many other ways people suffer and die early from pollution.

Can we try to raise the number of people pledging not to fly to at least 600? You can go right now to Flight Free USA and pledge not to fly for a year or, as I recommend, ever. You can even just pledge to fly less, which will help create community and support others. It’s trivial, seriously trivial, not to fly. You are probably not flying now. It will improve your life in exactly the ways you might fear it will worsen it, because addicts get less of what they think they get more of.

Another coincidental number

Coincidentally, the man who sold the slaves was my age today when he died. He went to Harvard:

John Ball Jr. was a Harvard-educated planter who lived in a three-story brick house in downtown Charleston while operating at least five plantations he owned in the vicinity. By the time malaria killed him at age 51, he enslaved nearly 600 people including valuable drivers, carpenters, coopers and boatmen. His plantations spanned nearly 7,000 acres near the Cooper River, which led to Charleston’s bustling wharves and the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

A more positive number

In 1791, Robert Carter III began freeing his slaves, ultimately 500 of them. Unlike people today counterproductively promoting sustainability as good for business by saving costs, Carter did it to live by his values.

Increasing efficiency or going through the motions of sustainability without changing your business usually increases your pollution overall: if you make a polluting system more efficient, you pollute more efficiently. Most businesses use the extra profit to grow.

Systemic change begins with personal change. Want planes to pollute less? Stop flying. Pledge at Flight Free USA.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees