Why it’s hard to help an addict stop

My friend brings addicts to rehab centers in California. He knows hotels where they hole up together doing heroin and such in modern-day equivalents of opium dens. They know him and that he doesn’t pressure them. He knocks on the door. They open it.

He asks, “is anybody ready?”

Usually they all pass, but sometimes one says, “I am,” and he drives them to rehab. He says that nearly every one, as the car starts moving, suggests one last hit in the bathroom of the doof restaurant down the road. He tells them from experience that if they do, they won’t continue the trip so they keep going.

He described the hotels rooms as other worldly. Pizza boxes and doof wrappers are everywhere. Uneaten pizza is covered with mold. There is urine and other bodily fluids. Spoons, lighters, pipes, and other paraphernalia litter the floor. Roaches, mice, and other vermin abound. Greater than anything else, he tells me, is the stench. He tells me that anyone who isn’t addicted would see these places as disgusting and unlivable.

My exercise to you, the reader, is to imagine these dens from the perspective of the addicts living in them. I recommend considering before reading on. He’s told me and it makes sense, though I wouldn’t have guessed it, and it’s relevant to us in our lives.

The addicts living in these dens connect with them in two main ways. First, they associate the space with the euphoria of their drugs, overriding their sensory experience. They don’t smell the stench or see the vermin or mold. Even when they aren’t taking the drug, the space and everything about it connects them to euphoria. The den feels good.

Second, they associate the space with a like-minded, supportive, nonjudgmental community. Everyone else they know tells them to stop and makes them feel shame or guilt. This group makes them feel understood. Addiction feels like more than the euphoria of the chemical or behavior. It solves a problem. It provides an escape. It supports.

The object of one’s addiction feels warm, essential, supportive, kind, and understanding. It feels like family. The prospect of losing it feels like losing warmth, the essence of life, support, kindness, and understanding. It feels like losing family. An addict will cling to that object as if to the things it represents, however wretched it seems from the outside.

A relative of one of them, say a parent, who didn’t empathize would see their child in a wretched place with wretched people. It would seem the height of obvious and a clear sign of caring to point out this wretchedness, tell them they could do better, and encourage them to escape.

How would this encouragement sound to them? It would sound like asking them to give up their best friend, or like kicking their baby in the face. Even if intellectually they know they can do better without it, the prospect of parting with it feels like parting with their deepest value.

Even people reading these words don’t get how important something their addicted to feels. I can give most people that feeling, though they insist for them it’s different, that they’re not addicted. If I say it bluntly to illustrate how much just telling someone to stop can be counterproductive, or expecting that telling them the facts will lead them to change behavior, people who ask me to illustrate it with them forget they just asked for it and get angry.

I’ll risk losing you to illustrate how people’s addictions feel like important parts of their lives that sacrificing would never be worth it despite overwhelming evidence that they’re hurting themselves and others. Having avoided flying for seven years, I’ve come to see the activity’s wretchedness and harm. How do you feel when you read the words: Flying pollutes and harms people; consider never flying again.”?

Everyone is unique. I don’t know how you felt or reacted, but the most common response is for people to tell me about how family, their job, some cultural imperative, or the like means they have to fly. They don’t think about the pollution, the people murdered, raped, and enslaved to acquire the fuel, minerals, and resources to enable flying, or how it degrades nature. They tell me how it helps provide the best parts of life. Flying feels warm, essential, supportive, kind, and understanding. The prospect of losing it feels like losing warmth, the essence of life, support, kindness, and understanding. An addict will cling to it as if to the things it represents, however wretched it seems from the outside.

If you aren’t too mad at me for feeling like I suggest you never visit your parent on the other coast, your in-laws on another continent, or whatever flying represents to you, as heroin represents to its addicts, how would you feel if I suggested considering never eating spinach again, or some healthy vegetable? Healthy vegetables improve your life. Most people who observe their mental reactions closely enough will acknowledge that intellectually, they know spinach is healthy for them and worth keeping in their lives, but they feel more attached to flying. Spinach doesn’t trigger addiction so, however delicious with a bit of lemon and garlic or however you prefer it, it doesn’t feel warm, essential, supportive, kind, and understanding. The prospect of losing it doesn’t feel like losing warmth, the essence of life, support, kindness, or understanding.

There’s nothing special about flying. Any number of substances and behaviors enabled by pollution create situations where we’re living in wretchedness: disposable things like diapers and packaging, doof, social media, fast fashion, and so on.

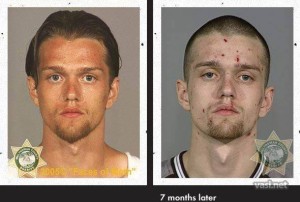

When we feel deep attachment to something unnecessary for life but gives us a predictable jolt of euphoria but also adverse consequences, we may be addicted, especially when that thing didn’t exist for our ancestral past, others feel the adverse consequences before we do, people manufacture it to cause us to crave it, and they promote it to say it brings us emotional reward (“Coke adds life,” “Because I’m worth it,” “you’ve come a long way, baby”). When we passionately defend such a thing and can’t see its wretchedness, we may be like the addicts my friends invites to rehab.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees