Affluence Without Abundance, Part 2: Hunting

When I last ate meat in 1990, maybe 1989, I tried to persuade others to stop too. I just ended up in arguments.

Since then, I’ve come to appreciate more views on the practice. I don’t see it as right, wrong, good, or bad. In fact, I get annoyed by people who try to impose their values on eating meat on others even if I share those values.

(I see reason to intervene on factory farming, animal cruelty, and a few related issues that affect others, though I haven’t made them my battle.)

Eating meat is an environmental issue for the pollution it causes and resources it depletes, though I see the issue rooted in human population. If the planet had 1 billion people, the pollution from animals raised for meat or depletion of, say, fish, wouldn’t be a problem. With few enough people, animals would regrow and plants would process the greenhouse emissions faster than we could affect them.

Isn’t any eating of animals cruel? Once the animal is born, it has to die. We can’t change that. I don’t think our humanity stops us from being animals and animals hunt and eat other animals. I can’t support any practices in the United States, given our outside environmental impact, and oppose factory farming anywhere, but we aren’t the only culture.

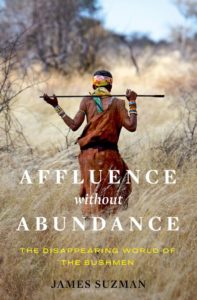

The book Affluence Without Abundance by James Suzman changed a lot of my views on how humans can live with their environment. Not that I hadn’t heard of hunting and gathering societies, but I hadn’t heard of them enduring for 200,000 years, which gives a new meaning to sustainability.

Hunting then and there

Affluence Without Abundance, by James Suzman

The passage below describes the people of southern Africa hunting. It’s a way that is about to disappear but still hanging on. I’m sharing it because it illustrates a practice I can’t complain about in its context.

Their hunting seemed more humane than our agricultural practice based on growth at all costs, chopping down rain forests, resulting in factory farming, and the like. We think of those things as aberrations, but from the book’s perspective they seem endemic to agriculture.

I hope we learn to enjoy life more without relying on growth and ownership so much.

Here’s the passage. Note that “Nyae Nyae” is a place. The /’ in Ju/’hoansi refers to one of the “click” consonants in their language we don’t have letters for.

Traditional hunts can last several days, and most people prefer some companionship if they are to sleep out in the bush. Also, two or three hunters working together almost always stand a better chance of success than a hunter working alone.

Nyae Nyae is also by far the largest of the last few places anywhere in southern Africa that San can hunt without fear of being prosecuted for poaching. But even so, far fewer men hunt regularly than did in the past. The most prolific hunters in Nyae Nyae are middle-aged and they complain about how only a few young men are interested in hunting and fewer still are skilled hunters.

While Ju/’hoansi in Nyae Nyae are free to hunt whenever and wherever they wish within the Nyae Nyae Conservancy boundaries, they are forbidden to hunt using anything but “traditional methods.†The only people allowed to hunt in Nyae Nyae with rifles are the trophy hunters, who pay big money for the privilege. There are also a number of species the Ju/’hoansi are forbidden to hunt by law and others they are forbidden to hunt by conservancy rules. These include giraffe, once a favorite meat for the Ju/’hoansi, and pangolin, much loved by the Ju/’hoansi but now endangered because of poaching to feed the Chinese medicine market.

No one resents the requirement that they much only use bows and arrows, spears, or traditional traps, and hunt only on foot—especially the few men who still hunt regularly and experience their environments in a similar way to their fathers and their grandfathers before them. For them the practice of hunting is a process in which their bodies and senses progressively merge with those of their prey up to and beyond the moment that the fatal spear thrust is delivered.

Unlike gently paced gathering trips, hunters usually set out with light-footed urgency, often chatting among themselves as they scan the ground for tracks. Sometimes they spread out to cover more ground, but just as often they march together in a single file, their fingers pointing out tracks in a twinkle of practiced gestures while their mouths talk about other matters. If the hunters are lucky they may find suitable fresh spoor early in the hunt. But it is not uncommon to walk for days, find nothing, and return home empty-handed.

Most of the larger meat animals Ju/’hoansi hunt, like kudu or wildebeest, aren’t particularly fond of the heat. It saps their energy and makes moving around a chore. So when the sun climbs above the tallest trees, they seek out patches of shade in which to disappear and will usually remain there until late in the afternoon. This is the best time to hunt. It gives hunters a chance to gain ground on prey that may have left a set of tracks five or six hours previously. It also allows the hunters to capitalize on one of their most obvious advantages over many prey species: their physical endurance and ability to cover large distances relatively fast.

Hunters will often choose their individual prey on the basis of its tracks alone. From among the tracks left by a herd of kudu or hartebeest, for example, it is easy enough for the hunters to establish which individual in the herd best suits their needs, which is likely to be easiest to kill, and which will have the most fat. Once the hunters decide to follow a promising set of tracks, the tenor of the hunt changes. Their pace increases and, if they talk, they do so in hushed, urgent tones, communicating only by means of hand signals. If the wind id favorable or there is no wind at all, the hunters will follow the track as it is written. But if the tracks lead downwind and the animal may be nearby, they will tack back and forth, intersecting the animal’s tracks now and again, so that they can approach it with the wind in their faces. And as the spatial distance between them and their prey closes, the hunters’ senses begin to merge every more completely with those of their quarry.

Once they locate their prey, each movement they make is dictated by an amplified awareness of their prey’s immediate sensory universe: what it sees, what it smells, and what it hears. Moving silently, knees bent and shoulders stooped, bows in hand, they experience the world around them from the perspectives of both the hunter and the hunted. As the hunted they are alert to every sound and movement the hunters make. As the hunters they are singularly focused on dissolving into the landscape and emerging undetected close enough to get off a good shot. A glassy shard of cloud passing overhead can reveal their presence as the passing cool of its shade induces a momentary breeze, as can a bird taking flight or a ground squirrel or lizard scurrying for cover. It is only once the hunters have stalked within forty yards or so of their target and an arrow has been released and found its mark that this hypersensory bubble dissolves.

If the shot finds its mark, the light reed shaft of the arrow falls to the ground often before it has been noticed by the prey, which feels no more pain in that moment than it would if it had been bitten by a particularly vicious horsefly or stung by one of the angry wasps that terrorize casual visitors to waterholes. Even then the hunters will be careful not to reveal themselves to their prey. Doing so would almost certainly spook the animal, causing it to flee. If it is not spooked, it is usually sufficiently disoriented by the pain that begins to seize it to remain close to where it was shot. At best death comes in a couple hours, but if it is a particularly big animal, like a giraffe or eland, it can take more than a day before it weakens enough for hunters to approach and kill it with their spears.

There is little point in following a particularly large animal once it has been shot. The stress of pursuit can affect the meat. It also saps the hunters’ energy. In these circumstances hunters will memorize the individual animal’s spoor and camp for the night where they are or, if they are not too far, return home. But returning home brings with it an additional set of risks. During the period a hunter and his prey are linked by the poison; hunters describe feeling shadow pains, often in the corresponding part of their bodies where the arrow struck their prey, or they feel unsteady as the poison gradually starves the animal’s organs of oxygen. But these sensations are neither overwhelming nor particularly distracting. The have form and presence yet no substance.

Returning into the human world of the village while waiting for the poison to do its work also risks severing the empathetic thread that bind the hunters to their prey. Back in the village the sense of shared anticipation, even if not vocalize often, amplifies the hunters’ anxiety that something may go wrong. Was the poison on the arrowhead sufficiently fresh? Was there enough? Did the arrow penetrate deep enough for the poison to enter the bloodstream? Might a rainstorm wash away the spoor and the animal die needlessly?

[ . . . ]

If all goes well, the final stage of the hunt is usually a formality. If the animal has not been spooked, then there is a good chance that it will still be somewhere near where it was shot. But if it has run or the poison works too slowly, the hunters will have a long walk before they claim their prize. Once they find it, they will unceremoniously spear it if it still has some life in it. By the time this happens, the animal usually will offer no response to the hunters, its sensory universe reduced to a haze of poison-induced pain, paralysis, and trauma.

For the Ju/’hoan hunters the moment of the kill is one of neither elation nor sadness. When I asked one man what he felt when he cut an animal’s throat, he replied that it felt no different than cutting bread. But this is understandable. It is hard to feel anything at all when overwhelmed by the almost postcoital sensory void that marks the end of a successful hunt.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees