The Ethicist: Can I Tell My Brother the Truth About Our Paternity?

My series answering the New York Times’ Ethicist column with an active, leadership approach instead of an analytical, philosophical perspective continues with “Can I Tell My Brother the Truth About Our Paternity?â€.

I’m 45, living in the United States. My brother is two years older and lives in Australia. Neither of us gets on with our 86-year-old mother, who lives in London. Our father, whom we were both really close to, died in 1985 after a long illness. I was 13, my brother 15, and it affected us very badly with little help from our mother.

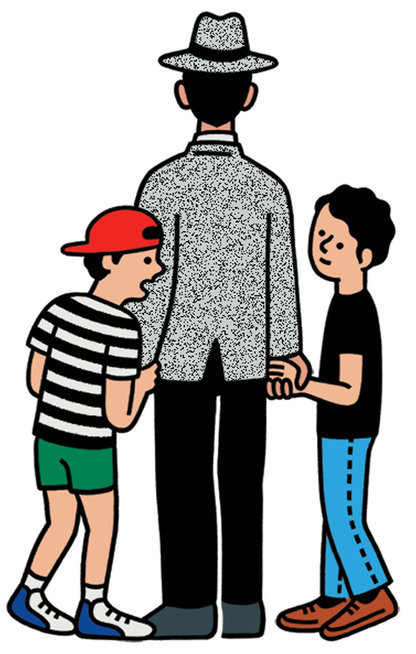

I recently took a DNA test out of curiosity for the health information and couldn’t understand the result that I was 52 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. As far as I was aware, both my parents were from Jewish families going back as far as we knew. The following day, having not spoken to my mother for a year, I asked if she wouldn’t mind taking the test. She responded that it was a route that I might not want to go down. Of course, I asked why, and she just came out with the news that my father was infertile and that both myself and my brother were from artificial insemination. She told me not to tell my brother and said that she never wanted to talk about it again.

I have been absolutely devastated by this news. Before speaking to my mother, I had mentioned to my brother that my DNA results appeared strange. He didn’t show too much interest. I genuinely do not know how my brother would react, as he is generally far less emotional than I. However, I am feeling a lot of guilt because I think it is everyone’s right to know such an important fact. As devastating as this news was to me, I am grateful to know the truth.

Doesn’t everyone deserve to know the truth? Should I tell my brother outright, or should I inquire if he wants more details about his heritage or simply not bring it up? Should I give my mother the opportunity to tell him before I do? My concern for my mother’s request not to tell him is of secondary consideration. Name Withheld

My response: Besides the problem you describe, you say you feel guilt and other emotion you don’t like. You can manage your emotional response—through, for example, choosing your environment, beliefs, and behavior—and I’ve never seen a benefit to suffering or being miserable. I recommend developing the emotional skills to manage your emotions. You’ll make yourself more effective in achieving your goals and feel emotions you prefer, which I call a better life.

I recommend a different perspective than asking what others think you should do. There are many choices you can make where you don’t know all the possible outcomes, who will like the results, who might get hurt, and so on. I think of it like looking down a ski slope that splits, the paths diverge so you can’t either past the first part, and you have to choose. Or choosing which wave to surf.

When you can never know all the information you wish you could but still have to choose or risk standing in the cold while others pass you by, in life or on the slopes, the best I can think to do is to know that whichever you choose, you’ll enjoy it or live it the best you can, and that you’ll take responsibility for making it work. Also not to judge your choice based on information or experience that came after you chose but couldn’t have known at the time.

In the meantime, “What should I do?†… Asking what you should do makes sense for children asking their parents. For an adult, it looks like asking someone else to take responsibility, which I call juvenile. Asking for options or views you might have missed makes sense, but you didn’t ask that.

The New York Times response:

“Grown-up people form a secret society, they must have something to hold by; they dare not say to a child: ‘There is nothing you do not know here.’ †So reflects a character in Elizabeth Bowen’s novel “The House in Paris†who has given up her child for adoption. (Or, to be precise, that’s what her child later imagines her reflecting.) With the sheer passage of time, a truth not yet shared becomes a truth withheld. At some point — but starting at no particular point — a difficult disclosure comes to feel like an impossible one.

I agree that your parents should have told you about the artificial insemination. In an ideal world, you would have had this conversation much earlier, with both your parents, and have had the opportunity to make the acquaintance of your biological father, if this had been something you both wished. Perhaps it will help to bear in mind the larger context: Your parents wanted children and took the only route, apart from adoption, that was available. You were the result. You and your father had a loving relationship. And your having been denied the facts about your biological paternity hardly cancels out all the good things in your relationship with him. Families aren’t really bound together morally by genes: They’re mostly connected by ties of love and experience.

Still, people tend to be interested in their biological ancestry, and as I’ve had occasion to note, these DNA tests mean that discoveries like yours are getting more and more common. You know your brother, and unless you’re confident he would not want to know this, you should encourage your mother to tell him and try to put things right. If she declines, though, you should tell her you’re going to do it instead. While your mother asked you to keep it from your brother, you don’t suggest that she revealed what happened on condition you did so: It was a request she made, not a stipulation traded for information. For what it’s worth, it sounds as if your brother won’t be as upset as you are.

I recently did 23andMe to learn about my genetic health and ancestry. A week after getting my results, I received a marketing email asking if I wanted to connect to the 1,000-plus other customers to whom I was related. I thought, Why not, as I might meet a distant cousin back overseas. To my surprise, I learned I had a first cousin born the day before my older sister and given up for adoption by my now-married-for-50-years aunt and uncle. No one in my immediate family was aware that they had given up a child before marrying and subsequently having four more children — cousins with whom I grew up and spent summer vacations. I waited for my adopted cousin to reach out to me, which she did after a few weeks, and we had a nice phone conversation. She informed me that her biological parents and four siblings responded to a letter she wrote to them 12 years ago that they want no contact with her or her daughters whatsoever.

Do I let my cousins know that I am now aware of what they have spent over a decade trying to conceal? I know of at least two other second cousins who also took a genetic test and learned of this genetic cousin through 23andMe. To me this seems like a ticking time bomb for my cousins and aunt and uncle. Between these mass-market genetic tests and social media, it is just a matter of time before folks learn of this secret my aunt and uncle have tried to conceal for 52 years. My new cousin seems perfectly lovely and looks exactly like her genetic younger sisters. I’m surprised they don’t want to meet her and her daughters but respect that is their choice.

Is it better to let my cousins with whom I have had a lifelong relationship know that I know this? Or do I wait until it all comes out via other channels and let them know then that I have known since 2018 and wanted to respect their desire for privacy with regards to this matter? Name Withheld

My response: There is no book in the sky or other measure of absolute right, wrong, good, bad, or evil that 7.6 billion people will agree to. If there were, you would have consulted it, gotten your answer and wouldn’t have had to write here. There isn’t, so you did.

You’re related to everyone alive. Despite Leave It To Beaver fantasies, families have had such situations since before humans existed. You can choose to create drama out of everything. You can choose to enjoy life. You seem to prefer drama, as you’ve taken step after step to embroil yourself in it. I suggest that the key is to realize you’re creating the emotional tenor. You can increase it or tone it down as you like.

The New York Times response:

Another family secret divulged by DNA. But the structure of the situation here is different. Everyone with a plausible claim to know already does. That your cousins want nothing to do with their sister is, as you say, their right. That they don’t want anyone outside the immediate family to know is also their right — but it isn’t, as you’ve discovered, under their control.

You’re convinced that the secret will come out eventually. Either way, keeping what you know from them gives them only the illusion of privacy. You’d seem to be precisely the kind of person — someone in their social circle — they hoped wouldn’t find out; the fact that they’ve failed in this objective is probably something they’d want to know. And keeping your knowledge to yourself is likely to disrupt your relationship with them, by introducing an element of artifice; when you’re with them, you’ll always be mindful of having to conceal what you know. (Those are the sorts of circumstances in which you make a Freudian slip.)

So tell them that you know and how you know and assure them that you won’t discuss it further if they so choose. That is, keep their secret — but don’t keep it a secret from them that you know it. You’re free, of course, to be in touch separately with your newfound biological relative if you wish to be, and even to keep her abreast of news about her down-low DNA relatives. But not telling your cousins until the secret is out and then revealing that you were already in on it? This would verge on disrespectful. Granted, they won’t be happy to learn that you’ve been in touch with their unacknowledged sibling. But they’d have more reason to resent your failure to let them know what you know.

As an engineer/manager at a Midwestern industrial facility, I recently had a gentleman presented to me who was being interviewed for a position similar to mine at the same location. I was acquainted with him from a three-year project with a previous employer on which I was the project manager. On that project, I engaged an engineering company near the job site so I could have its personnel perform site visits for me and save travel expenses that would have been required for me to make the visits myself. The gentleman in question was the individual provided to perform these site visits, and he spent less than 100 hours on my project performing the three or four site visits I assigned him.

I did not interview this person, but after his interview, I was asked to review his résumé. It states in his previous professional experience that he was the project manager on that very project, matching the dates of employment when I was actually performing that role.

If this gentleman is ultimately employed at my facility, I imagine it would not affect me adversely, as long as he stays out of my way. The employment market in my line of work is very limited at this time, and I know many who are struggling to find employment, so I can understand the temptation to pad one’s résumé. However, I find his flagrant misrepresentation of his work experience problematic.

I am not otherwise familiar with this gentleman’s capabilities or lack thereof. Am I morally required to report this person’s misrepresentation of his work history to my director? Name Withheld

My response: “Morally required?” Labeling something doesn’t change your situation. You probably want to resolve it more than label it. I suggest that more than a New York Times columnist labeling something for you, you’d benefit from developing the social and emotional skills to resolve the situation and improve your emotional well-being.

You’ll lose the excuse to say, “But the New York Times said I was morally required†but gain the ability to resolve these inevitable parts of life without needing others’ help. You’ll make mistakes, but you’ll learn from them. Experience is the best way to learn these things, I’ve found, as have millions of others. I recommend accepting the missteps you’ll make, looking at them as learning experiences, and using them to learn and grow.

Your writing is also needlessly wordy. You could cut a third of the words or more without losing any meaning, while gaining clarity so the reader doesn’t have to reread your message several times.

The New York Times response:

Résumés typically take a rosy view — prospective employers aren’t shocked by the job applicant who upgrades his merely proficient Tagalog to “fluent†— but putting things in a favorable light is different from asserting a flagrant untruth. You were asked to look at his résumé. You happen to have relevant information about it. Keeping what you know from your company would be letting it down. Employers are entitled not to be seriously misled about an applicant’s professional experiences. It’s the applicant’s fault, not yours, that this information may lose him the job. And if it does, there’s a good chance the job will go to someone else who is struggling to find employment.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees