Flawed By Design: UN Population Predictions Are Based on Faulty Models

Perhaps you’ve seen the headlines about tomorrow: World population to reach 8 billion on 15 November 2022, according to United Nations predictions. Are we overpopulated?

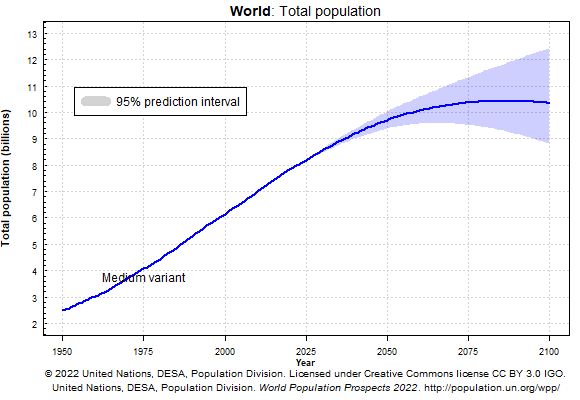

You’ve seen graphs of population projections from the UN showing the population leveling off or possibly decreasing by 2100 like this one.

Does the graph reassure you and make you feel good that the population problem is working itself out with no big collapse likely, nor that we keep growing forever.

Whew! The United Nations shows we’re safe. Right?

Wrong.

They were designed to look this way no matter what we do to the Earth. They only depend on past human demographics and nearly ignore the environment. That is, they are based on trends in birth rates, death rates, and migration, with minor adjustments for AIDS, Covid-19, and other small effects.

They’re like driving by looking only in the rear-view mirror.

“Wait,” you may be saying, “what about the risks of Florida and Bangladesh becoming under water, depleting aquifers, and things like them? Do such risks enter the calculations?”

No, they don’t. Moreover, they assume the birth rates will fall and lifetimes will always rise. When they update the projections, they only incorporate new demographic data. If the entire Amazon rain forest burned down or we depleted the oceans of fish, they wouldn’t change the projections.

In other words, something is missing. Their assumptions mean they could only find the population leveling off, possibly slightly decreasing. They can’t predict a collapse, no matter how much we lower Earth’s ability to sustain life.

The Basic Model the United Nations Bases Its Predictions On

The peer-reviewed paper The end of world population growth in Nature by Wolfgang Lutz, Warren Sanderson & Sergei Scherbov summarizes the foundation for nearly all the UN’s predictions in three main inputs:

The substantive assumptions about future trends in the three components of fertility, mortality and migration.

Nothing about resource depletion like extinctions, commercial extinctions, aquifers or rivers running dry, deforestation, or what you see in headlines. The paper includes some words about AIDS in Africa, but nothing about wars over resources or the projected billions of people migrating, which would presumably cause wars at borders. If a lot of people leave a place for lack of resources, they’re likely to overwhelm places with anything less than tremendously abundant resources, which don’t exist on the billion-person scale.

The model assumes birth and death rates will drop, assuring predictions of leveling off. Here are the main assumptions:

The total fertility rates assumed for 2025–29 are similar to those chosen by the United Nations2, but for 2080–84 they are assumed to range between 1.5 and 2.0, with lower levels for regions with higher population density in 2030.

We assume that life expectancy at birth will rise in all regions, except in sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV/AIDS will lower life expectancies during the early part of the century. In general, we assume that life expectancy increases by two years per decade with an 80 per cent probability that the increase is between zero and four years; but there are a number of exceptions to this rule based on specific regional conditions. These assumptions reflect the very large uncertainty that exists regarding future mortality conditions. On one hand, significant biomedical breakthroughs are likely to be made; on the other, AIDS could still become a major issue outside Africa, and new and unexpected threats to human life can emerge.

Another Paper Describes the Modeling

Lutz, in Dimensions of global population projections: what do we know about future population trends and structures?, describes the model inputs: “total size of the population . . . age, sex, rural/urban place of residence, educational attainment, labour force participation, parity status, household status and health status.” Again, nothing about the state of the world.

National Geographic described how they determine the inputs to the model at a high level in A World With 11 Billion People? New Population Projections Shatter Earlier Estimates, but that article still misses the point. When it says “people will still have to figure out how to feed nine billion” it should say, “the models only work if we figure out how to feed nine billion amid dwindling resources likely leading to widespread violence and refugees.”

If figuring out how to feed us all requires resources that would go elsewhere, such as police, health care, transportation, or other industries, what will happen to economies, local and global?

The United Nations Published Its Methods: Look for Yourself

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division’s report Methodology Report: World Population Prospects 2022 shows it uses roughly the above model, just more detailed. It doesn’t allow that resources may deplete, only new estimates of birth, death, and migration:

The preparation of each new revision of the official population estimates and projections of the United Nations involves two distinct processes: (a) the incorporation of new information about the demography of each country or area of the world, involving a reassessment of past estimates where warranted; and (b) the formulation of detailed assumptions about the future paths of fertility, mortality and international migration, again for every country or area of the world.

It allows for “Special considerations for countries highly affected by HIV and AIDS”, for Covid-19, and “Average relative risks of mortality by age and sex were estimated for nine categories of crisis events (battle deaths, conflicts, genocide (including mass killings), cyclones, earthquakes, epidemics, famine/droughts, floods, Tsunami)”.

Examples of Major Disruptions the UN Doesn’t Account For

How about two billion refugees?

Research at Cornell, in Impediments to inland resettlement under conditions of accelerated sea level rise, as reported in Cornell Chronicle:

In the year 2100, 2 billion people – about one-fifth of the world’s population – could become climate change refugees due to rising ocean levels. Those who once lived on coastlines will face displacement and resettlement bottlenecks as they seek habitable places inland, according to Cornell research the journal Land Use Policy, July 2017.

“We’re going to have more people on less land and sooner that we think,” said lead author Charles Geisler, professor emeritus of development sociology. “The future rise in global mean sea level probably won’t be gradual. Yet few policy makers are taking stock of the significant barriers to entry that coastal climate refugees, like other refugees, will encounter when they migrate to higher ground.

Earth’s escalating population is expected to top 9 billion people by 2050 and climb to 11 billion people by 2100, according to a United Nations report. Feeding that population will require more arable land even as swelling oceans consume fertile coastal zones and river deltas, driving people to seek new places to dwell.

By 2060, about 1.4 billion people could be climate change refugees, according to the paper. Geisler extrapolated that number to 2 billion by 2100.

This prediction from Cornell is not incorporated in the United Nations population predictions.

How about running out of clean water and depleting aquifers?

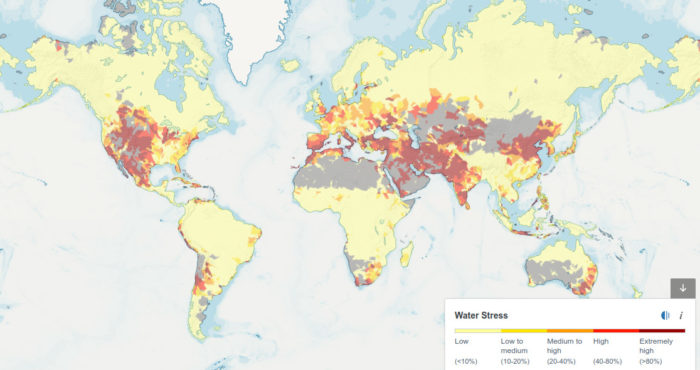

Here is a projection of water stress in 2030. There’s a lot of red (“Extremely High” stress) where a lot of people live. The CBC reports “1/3 of world’s major aquifers are being sucked dry, NASA data shows Social Sharing 8 of 37 biggest aquifers are ‘overstressed’ and 5 are ‘highly stressed’.”

How about topsoil degradation, pollution, and erosion?

How about overfishing?

You Can Incorporate Feedback. Other Models Do.

We can incorporate two-way feedback of humans affecting Earth and vice versa. A simple (probably too simple but useful to show it’s not hard) example is in the paper Footprints to singularity: A global population model explains late 20th century slow-down and predicts peak within ten years. It presents a simple model with feedback, which the UN predictions don’t. I consider it a useful exercise though again, likely too simple and could use input from other sources.

Despite its simplicity, as always, comparing with observation of nature is the final measure of any theory, and it was closer to the most recent results than the UN predictions. It noted:

During review of this paper, the first results of the global 2020 censuses began to come out. The US population grew by 7.4% from 2010 to 2020, much slower than the 9.7% growth observed between the 2000 and 2010 censuses. This implies, if the US population remains at 4.44% of the world population, that the world population last year was 7.45 billion, which falls within the range predicted by World4, 7.2 to 7.6 billion, but is well below the projections from the United Nations model, whose site reports a population of 7.79 billion for 2020.

The author of that paper, Christopher Bystroff, created its model, called World4 as a simpler version of Limits to Growth‘s model, called World3, which incorporates data, like the UN models, and feedback. Its simulations are widely misunderstood and mischaracterized by critics, but remain to me the best way to understand how human population will change in size based on demographics and two-way interaction with the environment.

Podcast guest Gaya Herrington researched and found that some of Limits to Growth‘s simulations correlated with the next fifty years of data. In science, predicting nature is the final measure of all theories. Limits to Growth gives (for those who read and understand it, not who mischaracterize it) what I consider the best understanding of human population in a changing environment where we affect it and it affects us.

More Background: Videos of the Main Researcher Behind the United Nations Predictions

Professor Lutz describes his model and more in a few videos on population.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees

Pingback: The UN’s three-pronged attack on sustainability » Joshua Spodek