Non-judgmental Ethics Sunday: What Should You Do When Customers Make Racist Remarks?

Continuing my series of responses to the New York Times’, The Ethicist, without imposing values, here is my take on today’s post, “What Should You Do When Customers Make Racist Remarks?”

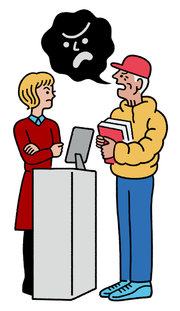

I grew up in New York and moved to a small Pacific Northwest ski town a year and a half ago. I work as a bookseller-manager at an independent bookstore. I love my job, but this election cycle brought out some heated feelings.

I am white, and the town is mostly white. A number of incidents in the past few weeks have made me uncomfortable and left me feeling helpless.

Incident No. 1: Every day we choose a book of the day. I chose “Another Day in the Death of America,†by Gary Younge. I had him as a professor for two semesters, had just finished the book and wanted to promote it. An older white lady asked me about the book, and I gave her a summary and mentioned I had a personal connection to the author. She asked where I went to school. I told her New York City. She proceeded to go on about inner-city violence and how her son lived in New York and she wanted him to be aware of the guns and isn’t it a shame. She talked about how everyone she knew had guns, but they weren’t shooting anyone, and it was those “Ferguson people†who were the real problem. I did not know what to say and thankfully she checked out and left.

Incident No. 2: An older white couple came in looking for a specific book. They did not know what it was called and only knew it was about Detroit before the recession. Somehow the husband got onto the topic of inner-city problems. I engaged him lightly, trying not to show my horror when he said that everyone was on drugs in Chicago and Detroit. He went on to say that the government should just stick them all on an island, airdrop food and let them kill each other; he did not want his taxes to go toward helping them.

I have been thinking about this a lot. I do not know what my ethical position should be when people express their offensive opinions and I am just trying to sell them a book. Granted, I will try to put something like James Baldwin or the new essay collection “The Fire This Time†onto people’s radar. I know I am giving my opinion and may be seen as an outsider who has some “agenda,†but what can I do when people say offensive and destructive things while I am at work?

What would a good response be? I feel strongly that the opinions they have just shared are negative and detrimental to conversations about race and this country. But how do I balance that feeling with respecting my customers? I feel like I cannot say anything, yet they are perpetuating hateful beliefs. I have kept my mouth shut and smiled and tried to not give my opinion, but I feel like I am ignoring my own disgust and somehow perpetuating racist beliefs. Name Withheld

My Response: The top line answer starts with what do you mean by a “good” response? What are your goals? If you want to vent, say anything you want. If you want to influence them, I suggest you’ll more likely motivate them to dig in their heels giving them James Baldwin—that is, you’ll achieve the opposite of your goal.

You write: “I know I am giving my opinion and may be seen as an outsider who has some “agenda,†but what can I do when people say offensive and destructive things while I am at work?“

From their perspective, and from the perspective of polarizing and alienating others, how is what you do any different? Is it that you’re right and they’re wrong? Don’t they feel the same way?

I ask you: Do you want to win debates or enjoy life? and suggest: Don’t be Walter. If you want to influence someone, you’ll be more effective if you show you’re open to influence and if you get to know the person beyond a few sentences they say in a bookstore. How open are you to their influence and come to agree to with them. If you aren’t why do you think they’d be open to you? Because you’re right? They think they’re right.

The New York Times response:

You speak of racist beliefs. There seem to be two kinds here. One class consists of false statements of fact: It isn’t even a reasonable hyperbole to say that every African-American in Detroit is on drugs. What makes beliefs like these racist (and not merely mistaken) is that they tend to reflect hostility toward black people in general and a consequent biased reading of the evidence. Sometimes people are simply passing on thoughts they have acquired from others without much reflection. But in this day and age, accepting beliefs of this sort is usually a sign that you have negative attitudes. The false beliefs are not the basis of the attitudes; it’s the other way round.

A second class of beliefs is inherently repugnant, not merely in their genesis (or their effects) but in their content; they convey sentiments toward people that nobody should have. Fantasizing about dumping black people onto an island where they kill one another — you don’t need fact-checking to see the moral problems here. You mention the election cycle. It hasn’t escaped notice that President-elect Trump’s speeches have encouraged the expression of racist attitudes and ideas. Demons have been loosed, and I suspect we will be living with the consequences for some time.

So the problems that you describe aren’t likely to go away anytime soon. You have a couple of responsibilities here. One is as the manager of a business. You don’t want to drive away too many customers. But a second is as a citizen. When citizens address one another in the course of everyday interactions on topics of public morality, they should speak to each other truthfully and respectfully. When someone says something morally repugnant, failing to respond with disapproval is failing to take that person seriously as a moral agent. It’s a sign not of respect but of contempt, or perhaps cowardice. If you say nothing, you may give the impression that you agree, or at the very least that you think what they’re saying falls within the range of respectable opinion. The episodes you cite fall outside that range.

Your challenge is to find a polite way to say that you disagree. If your customers defend what they have said, you have the opening to argue against their views. But precisely because their views are likely to be rationalizations of a previous antipathy, they may not be terribly susceptible to reasoned argument. Getting angry probably won’t help, either. Try something like, “If you knew more about the lives of black Americans, you wouldn’t say that.†And then offer one of the books you mention. (Or show them this column.)

My summer house is in a remote area of the Ozarks. Our new neighbors are hard-working, pleasant people, but they are hoarders of junk and — worse — dogs. These poor creatures live in pens or are chained up outside. Last count: more than a dozen. I researched animal-cruelty laws in my state (Missouri), and it seems that unless the dogs lack adequate food, water, shelter and health care, it is difficult to prove neglect. (The state does have an anticruelty law that could be applicable, but it hasn’t adopted an antitethering law.) But where do the dogs come from? Where do they go? New ones appear from time to time, but many live day in, day out in the same deplorable conditions. When I talk to one of my neighbors about the dogs, he is quite proud and seemingly fond of them. I could report my neighbors to an animal-cruelty organization or have friends report them, but either way, because of our remote location, my neighbor is likely to suspect that I reported him, and I could find myself losing my vacation home in a mysterious fire. Plus, it is likely that the lax laws in our state won’t help the animals anyway. We are currently on friendly terms with the neighbors, but I can’t stand to see the animals treated this way. I believe hoarding is a mental illness and no amount of reasoning with the neighbors will help. Name Withheld

My Response: Again a message with no question. It has two question marks, but they read like rhetorical questions.

The typical question letters to this column ask is what is ethical or what the writer’s responsibility is. I’ll presume this writer isn’t asking about labels but what to do. Like the letter above, I don’t see short-term actions or responses having much effect. The dog owners sound like they believe what they are doing is right. If you feel differently, even if the law agrees with you, your reasons aren’t likely to influence them.

It sounds like influencing him will take leading based on their values, not yours. If they believe what they are doing is right, your differing values won’t influence them. You’ll have to get to deeper and deeper ones until you reach ones that lead to taking better care of the dogs, which likely means behaving more and more so they will feel comfortable sharing vulnerabilities with you. That’s a challenge. Without them agreeing that something they’re doing is wrong, I don’t see much of how to influence them.

If you don’t feel the law can act effectively, involving it—that is, trying to coerce them with authority—will likely lower your ability to influence them. If you try and it doesn’t work, you may never influence them. If you were to go that route, I would suggest first getting to know them more and non-judgmentally sharing that you disagree with how they treat the dogs, maybe showing them the law that you didn’t make up, then saying you consider it your responsibility to the dogs to have an authority look at their conditions.

That is, I recommend acting by the principle of not surprising people.

The New York Times response:

Some experts think animal hoarding is a psychiatric disorder, and there are tools for assessing the problem and some approaches to treating it. That disorder might thwart intervention, because one of the symptoms is difficulty in recognizing that you have a problem. But the way you describe your neighbor, he doesn’t meet many of the criteria on the Homes Multidisciplinary Hoarding Risk Assessment. So your neighbor might be unaware of any cruelty here. If you’re sure he’s doing wrong by these animals, you have a strong reason to try to get him to change his ways.

What about talking to the neighbor about why the dogs might be better off if they were treated differently? Encouraging him to find other homes for some of them, and perhaps offering to help with that? If the dogs need exercise, you might also volunteer to take them for walks, explaining that you would enjoy spending time with them.

But you don’t mention the possibility of having a conversation along these lines, and that’s presumably because you don’t think it would do any good. Maybe you’re right. Maybe in the Ozarks interventions of this sort would be considered nosy or officious. Maybe your neighbors are indeed beyond reason. Even though you’re “on friendly terms,†you clearly think your neighbor is capable of being dangerously hostile if he takes against you. If your understanding of the situation is correct, there’s not much you can safely do. But (again, bias alert) what evidence do you have of that? Perhaps you’re being influenced by stereotypes about country folks of the sort promulgated by “Straw Dogs†or “Deliverance� Since you’re doubtful that reporting your neighbor will help these dogs, a conversation may be your only option.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees