Non-judgmental Ethics Sunday: Can I Tell a Dying Friend’s Secret to His Children?

Continuing my series of alternative responses to the New York Times column, The Ethicist, without imposing values on others, here is my take on today’s post, “Can I Tell a Dying Friend’s Secret to His Children?”

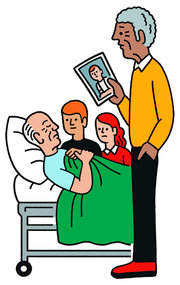

One of my closest friends is dying of cancer. He will leave behind a wife, an ex-wife and two children from his first marriage, both of whom are over 21. I’ve known him for 40 years, and I believe I am the only person in his circle of friends and family who knows that he has another child with another woman. That child is probably close to 30 now. My friend has had no contact with the child since birth and almost no contact with the child’s mother. This appears to have been the way they both wanted it.

When my friend’s cancer was diagnosed (a type that is almost never curable), I urged him to consider telling his children about their half-sibling. He said he would think about it. He’s now close to the end, and he has not done so. At this point, I don’t think he is capable of telling them.

He has asked me to be the trustee for the trusts he established for his two children, and I have agreed. So I will continue to be involved in his children’s lives for many years. I think the children have a right to know about their half-sibling. But obviously my friend did not want them to know, or he would have told them himself.

What are my ethical obligations? I am not going to lie if they somehow find out about the child through other means and ask me if it is true. But am I ethically bound to honor my friend’s wish that his children (and wife) not know? Or should I follow my own conviction that children have the right to know these things? Name Withheld

My response: While I can see an abstract debate here, I see it as academic. It’s not even obvious he didn’t want them to know versus he didn’t want to tell them, where the latter says something about his willingness to speak, not about what he wanted them to know or not. Beyond that abstract, academic debate about labeling, I don’t see much of a problem with you doing what you feel is right.

I still feel compelled to point out there is no concrete definition of “ethical obligation,” at least as far as I know. I would have phrased the question more like “what values and considerations do you consider important so I don’t miss any?” The more you learn to handle issue like this yourself, the more you’ll learn your values and be able to act on them independently. I think you’ll like your life more that way.

The New York Times response:

When information is given to you on condition that you keep it to yourself, you’re obliged to give serious weight to the compact of confidence. But the simple fact that a person doesn’t want to disclose something, even something about himself, doesn’t have the same gravity. Once your friend is gone, you may judge that the negative consequences that concerned him (say, the changed view of him among his remaining family) are less significant than the interests of the living. As long as he can still understand you, you might want to tell him what you plan to do. It would be good to be clear about his reasons for keeping the other child’s existence from the family before you decide to override them

I have been good friends with someone for more than 50 years and have lived with him for nearly five. Several years ago, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He decided not to treat it. Now the cancer has metastasized to his abdomen, his bones, etc. His doctors have suggested he has six to 12 months to live. He has asked me not to tell anyone of his illness, not even after he dies. Other than his doctors, I think I am the only person who has this information.

He is estranged from most of his family except for one sister whom I have met and who I know loves him dearly. She would be devastated and angry not to be able to say goodbye.

Do I keep my word to my friend, or do I tell his sister? If I tell his sister, when do I do it, and how do I explain my action to him? Name Withheld

My response: You wrote “he asked me not to tell anyone of his illness,” then asked, “Do I keep my word.” I don’t see that you gave your word. If you did, then at least after he dies, it seems your main issue is one of integrity—how you behave when no one can see you. Do you mind sacrificing your integrity?

I recommend next time someone asks to tell you something in confidence, that you not give your word before knowing the information. I stopped making such blind promises and found that people appreciated telling me and letting me choose after. I now view as childlike someone saying, “If I tell you something will you promise not to tell anyone?” I respond, “If you want to tell me you can, but I can’t promise about something I don’t know. For all I know you’ll tell me you murdered someone and I won’t keep that secret.” Like I said, I have found that response builds relationships. I haven’t found blind promises to improve relationships.

The New York Times response:

Another man with secrets he would take to the grave. In this case, though, he seems to have exacted a pledge of confidence. When you give someone your word, of course, he or she can release you from your promise. So the right start here is to tell your friend you think he ought to let his sister know what’s going on, or let you do so. You should ask him to consider how his sister would feel, and whether she wouldn’t be right to feel this way. You could also offer to help him manage his interactions with her, were he to have a change of heart. (It sounds as though he and his sister aren’t that close, though; otherwise she’d see him deteriorating when they visit each other over the next six to 12 months.) But if he holds you to your promise, you should keep it. You may be convinced that he’s making a mistake in trying to keep his medical situation a secret, but it’s his mistake to make.

I am a scientist with a Ph.D. in the biomedical field. I routinely am asked for medical advice by friends and family, presumably because of my “doctor†title. Although I have developed a significant base of medical knowledge by conducting medical research, I have long felt that it is unethical for me to provide informal medical advice because I do not have formal medical training and licensure. However, with the popularization of “natural†and “alternative†medicine, many people are getting poor medical advice from either the internet or naturopathic doctors, and I have been forced to reconsider my position.

The scientific consensus is that the vast majority of these alternative remedies are either ineffective (homeopathy) or potentially dangerous (organic solvents). Eschewing conventional medicine in favor of natural remedies is, at best, a waste of money, or at worst, fatal, in the case of serious diseases.

Also, does it matter how serious the condition is? One of my hesitations lies in that many alternative and naturopathic practitioners are licensed (and therefore legitimized) by the state, whereas I am not a licensed health care practitioner. Name Withheld, Thunder Bay, Canada

My response: This column is the “naturopathic” and “alternative” equivalent of personal development that could come from examining your values, searching for alternative solutions, considering what resources you have, and solving your problems yourself. Or at least working at them instead of asking people to label the limited solutions you’ve come up with with abstract philosophical words.

What do you think? Do you think the things you asked are ethical? Why or why not? How do you answers affect what you will do? Do you think you have a moral obligation? Why or why not? If someone tells you you do, what does that mean if they disagree? Would you change your opinion if they disagreed? What does that say about your personal sense of right and wrong? Can you answer your questions for yourself? Why or why not? If not, do you think you should be able to? If so, why are you asking? Could you ask more helpful questions? What would those questions be?

The New York Times response:

Answering general questions about medical science is not practicing medicine — which is, indeed, something you’re not entitled to do without a license, however knowledgeable you are. If you are going to advise friends on the poor evidence base for particular treatments, to be sure, you should probably rely on more than a consensus that most alternative remedies aren’t effective. It will help to be able to speak about the absence of evidence for the specific treatment in question. It’s also useful to bear in mind, when you discuss such matters, that treatment is about making people better, whether or not we have a good account of why it works. Aspirin was used for the better part of a century before its mechanisms of action were understood, and was developed from willow bark, which was used as a drug in Pharaonic Egypt. For patients, the pressing question isn’t: What’s the scientific explanation? The pressing question is: Is there evidence that it works?

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees