Op Ed Fridays: Challenging beliefs on men and masculinity

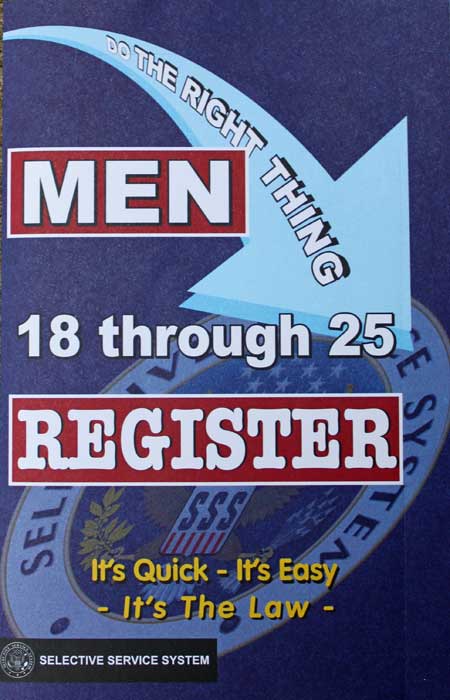

When I turned 17 I received the letter from the federal government that they required me, by my next birthday, to register for what it called Selective Service and and that I call the draft.

I don’t remember the details, but I remember something about punishment if I didn’t. I also remember thinking I didn’t feel I had the experience or maturity to comprehend this obligation imposed on me to risk my life and possibly have to kill others.

Neither of my sisters received a comparable letter.

The experience was one of the first I realized that society treated men differently—expecting us to risk death and killing. It felt sexist.

Years later, I remember my mother describing my step-brother’s relationship with his ex-wife as her abusing him. At first I didn’t understand. He was a strong man. How could she abuse him? My mom explained that the ex-wife used the apparatus of the state like a weapon and that my step-brother couldn’t do anything to fight back.

The system worked for her against him.

Years later, as an adjunct professor at NYU, in a faculty committee I participated in whose purpose was to promote leadership education, I remember a meeting with 12 women and 2 men in which people said there were not enough women and we should work to increase female representation. That committee never had a lower ratio than 2:1 female to male. The university overall is something like 3:2 female to male.

I remember taking the SEPTA bus to junior high school in Philadelphia passing by a W.I.C. office—to help women, infants, and children—but never one for men, despite nearly all the homeless I saw being men.

My high school—Central High School in Philadelphia—went coed the year before I started. My college—Columbia—went coed a couple years before I started there. Yet each school had an all-female school across the street from it that remained single-sex, disallowing men. In fact, both sister schools still reject all men.

People tell me that my education was about the culture and history of men. While more of the names in textbooks are men’s names, I never felt that Napoleon’s being male made me feel he represented me.

That is, people told me that I had a voice—in fact, an overrepresented voice—simply for having the same sex as some people, which they used to silence my voice.

Take Back the Night

In college I attended a Take Back the Night event. It so overwhelmed me with emotion that the next year I volunteered on the committee that organized it. I participated as everyone else did, but something always felt off. People described feminism as promoting equality, but I didn’t feel equal. I wondered if I should call myself feminist for participating. I think I tried but it didn’t stick.

What was going on?

All of the above treatment of men and me as a boy and man made me feel funny about the view of society as dominated by a patriarchy. My government ordering me to register to kill or be killed didn’t make me feel in charge. My step-brother’s ex-wife abusing him, as my mom characterized it, didn’t sound as if he were in charge.

The mainstream model of a patriarchy conflicted with my experience and observations in these areas that seemed important to me.

I didn’t think much of this conflict, though. I mostly followed the patriarchy view and was busy with other things to think critically about it. After all, men held nearly all positions of authority in government, business, religion, and so on. Men are physically stronger. These conflicts seemed minor in comparison.

A new view: The Myth of Male Power?

A few years ago I found forums online of men talking about similar experiences and more. Some wrote about sexism against men, which I found preposterous, despite the conflicts above. Putting them together here in this post makes them look related, but since they came up in my life decades apart, I didn’t think of them as connected.

On the contrary, I thought these men were talking nonsense, acting like victims when they weren’t. Some referred to a book, The Myth of Male Power by Warren Farrell. I thought, “here’s my chance to rip these ideas apart.”

I borrowed the book from the library and prepared to take apart whatever nonsense it spewed.

Instead, I found it explaining the conflicts above more than anything I’d read. Many things started making sense that never had before, including ones I hadn’t been sensitive enough to notice.

I write a lot about beliefs and how they influence how we see our world. I teach the skill of making yourself aware of your beliefs and changing them. The Myth of Male Power changed my beliefs as much as any other work.

I found the book well-written and well-researched. Since reading it, I’ve tried to explain it to others, but I couldn’t express it effectively, always leaving important parts out. I’m sure Farrell took years to write to communicate its ideas and I couldn’t match his results.

I’m bringing it up now not because I think I can express it any more effectively but because I recently found an interview of Farrell where he summarized the book better than I could and it’s printed under a license that I can redistribute it.

Rather than try to match his expression, which I haven’t been able to do, I’ll post the long interview so interested readers could get his message directly from the source. Here it is, in two parts. I’m not saying I agree with it. I do recommend reading it, even if you expect to disagree, as I did.

- The Myth of Male Power: Why Men Are the Disposable Sex, Part 1

- The Myth of Male Power: Why Men Are the Disposable Sex, Part 2

As I’ve said, the book changed my beliefs in an important area more than nearly any other work. Many people call the book controversial. Frankly, the vehemence and anger with which I’ve seen people attack him, part of me is scared to associate myself with the book. But I find it explaining a lot of things that nothing made sense of before and I don’t feel I should let that fear silence me, especially when I’m only suggesting people read it.

I’m also interested to learn your thoughts on it.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees