Our culture destroyed theirs, but which had better health, mental health, meaning, and purpose?

In a podcast post last week where I shared how history, anthropology, and archaeology contradict many of our views that we are living in the best times. This view leads us to think, “we may have pollution, but at least we live better than any time before,” which leads us to fear reducing our consumption, which leads nearly everyone to focus on increasing solar, wind, and nuclear first, reducing fossil fuels second.

Here’s that episode:

This view and strategy are catastrophic. For one thing, solar, wind, and nuclear aren’t sustainable. They require fossil fuels at every stage from manufacture to installation, maintenance, and disposal. The bigger issue is that given new energy sources, we use the new ones and the old ones. We aren’t reducing.

A Big Chink in the Armor

A big chink in the armor of that model is something I read in The Dawn of Everything, that in American colonial times, when European colonists lived with Indians, they tended to stay, but when Indians lived among Europeans, they tended to return.

My conclusion: one culture can destroy another by being stronger, say by having more guns, while the people in it have lower marks of health, mental health, resilience, equality, meaning, and purpose. If so, it implies we today could gain all those things by living more sustainably, at least to the extent mainstream overindustrialized society descends from those colonists and the Indians were living sustainably.

So I started researching. It turns out a rich vein.

Benjamin Franklin:

“When an Indian child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and makes one Indian ramble with them, there is no persuading him ever to return. [But] when white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and lived a while among them, tho’ ransomed by their friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good opportunity of escaping again into the woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.”

French-American Hector de Crèvecoeur in 1782, in a set of essays Letters from an American Farmer, the first American literary success in Europe:

“Thousands of Europeans are Indians, and we have no examples of even one of those Aborigines having from choice become European. There must be in their social bond something singularly captivating and far superior to anything to be boasted of among us.”

David Brooks in 2016:

In 18th-century America, colonial society and Native American society sat side by side. The former was buddingly commercial; the latter was communal and tribal. As time went by, the settlers from Europe noticed something: No Indians were defecting to join colonial society, but many whites were defecting to live in the Native American one.

This struck them as strange. Colonial society was richer and more advanced. And yet people were voting with their feet the other way.

The colonials occasionally tried to welcome Native American children into their midst, but they couldn’t persuade them to stay. Benjamin Franklin observed the phenomenon in 1753, writing, “When an Indian child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and make one Indian ramble with them, there is no persuading him ever to return.”

During the wars with the Indians, many European settlers were taken prisoner and held within Indian tribes. After a while, they had plenty of chances to escape and return, and yet they did not. In fact, when they were “rescued,” they fled and hid from their rescuers.

Sometimes the Indians tried to forcibly return the colonials in a prisoner swap, and still the colonials refused to go. In one case, the Shawanese Indians were compelled to tie up some European women in order to ship them back. After they were returned, the women escaped the colonial towns and ran back to the Indians.

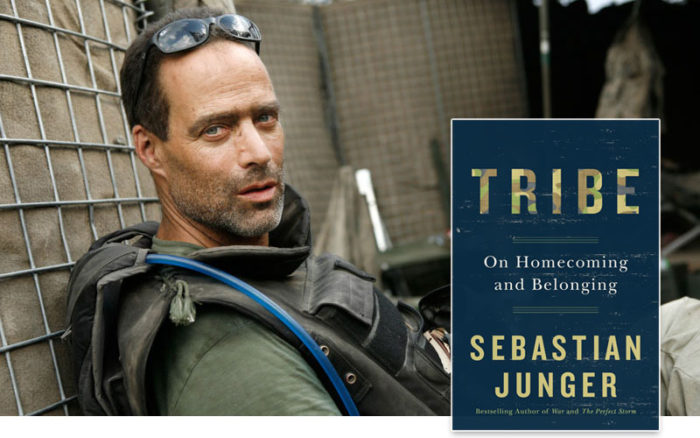

The above quotes led me to journalist Sebastian Junger‘s book Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging:

“There’s no use arguing that modern society isn’t a kind of paradise. The vast majority of us don’t, personally, have to grow or kill our own food, build our own dwellings or defend ourselves from wild animals and enemies. In one day we can travel a thousand miles by pushing our foot down on a gas pedal or around the world by booking a seat on an airplane. When we are in pain we have narcotics that dull it out of existence, and when we are depressed we have pills that change the chemistry of our brains. We understand an enormous amount about the universe, from subatomic particles to our own bodies to galaxy clusters, and we use that knowledge to make life even better and easier for ourselves. The poorest people in modern society enjoy a level of physical comfort that was unimaginable a thousand years ago, and the wealthiest people literally live the way gods were imagined to have.

And yet.”

— Tribe

I’ve been listening, watching, and reading Junger’s material, including Tribe. I recommend his TED talks, CSPAN videos, and Joe Rogan podcast appearances. Here are a couple highlights:

From a blog reviewing that Tribes:

Suicide is another area where the comparison between modern society and tribal societies is illuminating. Among the American Indians depression based suicide was essentially unknown. And when the Piraha, a tribe that lives deep in the Amazon, were told about suicide they laughed because the idea was so hard to comprehend.

. . .

You may have recently heard that recently there has been a big increase in deaths among the white working class. This was first pointed out by Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton and his wife Anne Case when they published a paper showing that while every other group was experiencing a decrease in mortality, for white working class individuals the death rate was going up. It’s unclear why it took so long to notice this, but now that it’s been pointed out the trend is an obvious one and it meshes very well into the opiate epidemic which I wrote about previously. As more information has come out about the nature of these deaths and as the phenomenon get’s more attention it’s acquired a label: Deaths of Despair.

I’m going to go a little bit out on a limb here, and engage in some speculation, as well, by declaring that rising levels of PTSD and deaths of despair are just the tip of the iceberg. That we have a real and growing problem and that progress is making it worse. Most people are going to find that hard to believe, and it’s easy to talk about the benefits of progress and modernity if you’re not one of those that progress has left behind. And to be clear its beneficiaries get to do most of the talking, while it’s victims have been largely silent. Thus you end up in a situation where when the half of the country that hasn’t gotten quite as good deal elects someone which, at one point, was declared to have a better chance of playing in the NBA Finals than winning the presidency, it’s doubly shocking. First, that it happened at all, and second that no one saw it coming. But that’s the part of the iceberg that’s under water. We may notice the deaths (eventually) but they sit on top of a huge number of people who are experiencing all of the things that Junger was talking about: They don’t have anything left to struggle for, and they certainly don’t have a community to struggle with.

The drug overdoses, the alcoholism and the suicides all sit on top of a large group of people suffering from the disease, whose symptoms are largely invisible. These sufferers include males who don’t have a single close friend or spouse to say nothing of a community. It includes the millions of people who’ve given up looking for work. It includes some of the 1 in 3 millennials who live at home with their parents, 25% of whom are not working or going to school. And it probably includes the people who have decided that it’s easier to sit at home and play video games all day.

Normally it’s easy to dismiss stuff like this by saying that things are getting better, the world is getting richer, technology is getting cooler, everything is getting easier. But those arguments don’t work in this case, because all of those things are very probably making the situation worse. And if they are making it worse how much worse is it going to get?

Our world is full of assumptions. We assume that eliminating struggle is a worthwhile goal. We assume that an eventual life of leisure is what everyone needs. We assume the past was worse than the present. We assume we know what we’re doing. And we assume that peace is always good and war is always bad. And when we make an assumption with disastrous consequences, we correct it, but what about when we make assumptions that have subtle negative consequences, creating diseases of society that only turn up only years or decades later? If this is what’s happening, will we be wise enough to examine all of these assumptions and admit that maybe we’re wrong?

The view that brings it all together

This history that we lack community and thrive under challenges where the group needs us looks like a linchpin or keystone that brings my movement to fruition. I’m not proposing giving things up. I’m proposing restoring what we’re missing in our isolation, ordering takeout, consuming doof, flying around destroying community and connection. No wonder I’m finding so much joy, meaning, and purpose in what others see as pointless work.

It augments the connection to nature I see we’ve lost.

Anyway, I was researching this view for my book and workshops, so I could refer to research, not my opinion. Benjamin Franklin and Tribe seem pretty solid sources.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees