Visiting the Jackie Robinson Museum

The Jackie Robinson Museum offered free admission this weekend. I didn’t know about it and don’t remember how I learned of the offer, but it turns out it’s a 20-minute walk from my front door so I took them up on the offer.

I recommend the museum to anyone. I presume most Americans know Jackie Robinson as the guy who “broke the color barrier” in baseball. Scroll to the bottom of this page for the overview of his life from Wikipedia, which is fascinating.

This museum shows his life from childhood, born in Cairo, Georgia, his father disappeared, his mother brought his family to relatives in Pasadena, California as part of the Great Migration, becoming a star athlete (along with his brother). He was UCLA’s only student to letter in four sports—track, football, basketball, and baseball—and I believe remains so.

For his baseball career the museum roughly equally treats his athleticism, his professionalism, and his facing racism. Even before becoming rookie of the year, his first professional game, for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor league team in Montreal, he dominated. If I remember right, he got on base 4 out of 5 at bats, stole bases, and helped lead the team to a 14-1 victory. The museum recognized the manager who signed him, Branch Rickey, for some credit, along with other players and people who supported him.

The museum also portrayed his career after baseball, as a business executive, writer (including newspaper columns and five autobiographies), political activist who worked with at least four presidential campaigns, and civil rights activist. It included some conflicts, including with Paul Robeson and Malcolm X.

He died young, at 53, of a heart attack.

The museum treats him and his wife, Rachel Robinson, as a team facing the challenges of racism. They met in college and stayed together the rest of his life. She described meeting him as nearly love at first sight, despite expecting before meeting him that being a star athlete big man on campus might have made him full of himself. She has run the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which runs the museum, since he died. I talked to some staff at the museum and it turns out she is still alive, at 103 years. The museum has many artifacts and replicas, including his first contract, her wedding gown, and many newspaper clippings.

It also shows videos, one of which prompted me writing here. Most of the media representations I’m familiar with show him playing baseball or speaking in his capacity as a civil rights activist. The museum had plenty of such footage, some of which you can see on the museum’s page or throughout the internet. What prompted me to post were several images that were gut punches to me showing the challenges he faced.

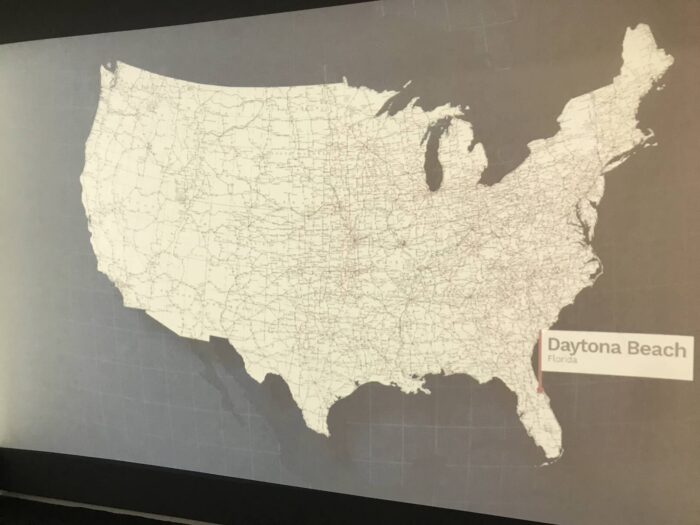

One video showed his and Rachel’s traveling to one of his first professional games, in Florida. They flew from California. An airline took away their seats in the leg from New Orleans to give to a white couple. They took a bus the rest of the way. He had faced discrimination traveling to play in the negro leagues, but she had never experienced it in person. They were forced to sit in the back of the bus. She used the bathroom for whites only.

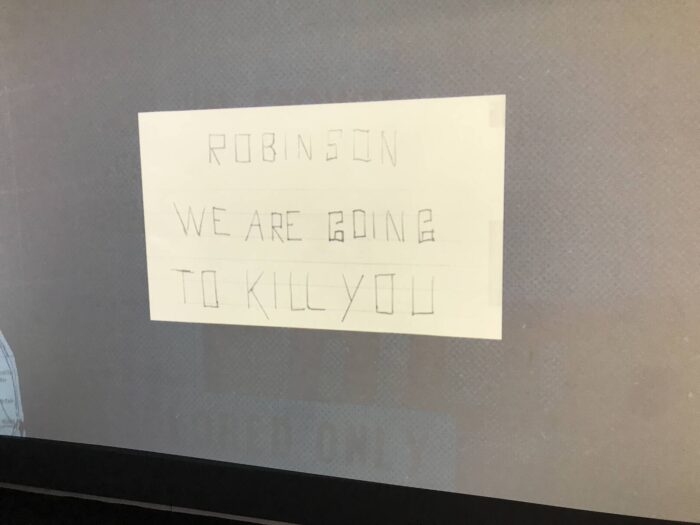

Two images from the video hit me. One was this card, reading “Robinson, we are going to kill you.” It was one of several written death threats the museum showed. I knew he faced discrimination and resistance as a player. I hadn’t thought much about how it manifested beyond other players saying they wouldn’t play with him. Notes like this one, appearing to come from someone deranged and angry, and therefore appearing credible, made clear that he risked his life every day of his baseball career and beyond.

This image from that video showed the route. Sorry, I didn’t catch the full route.

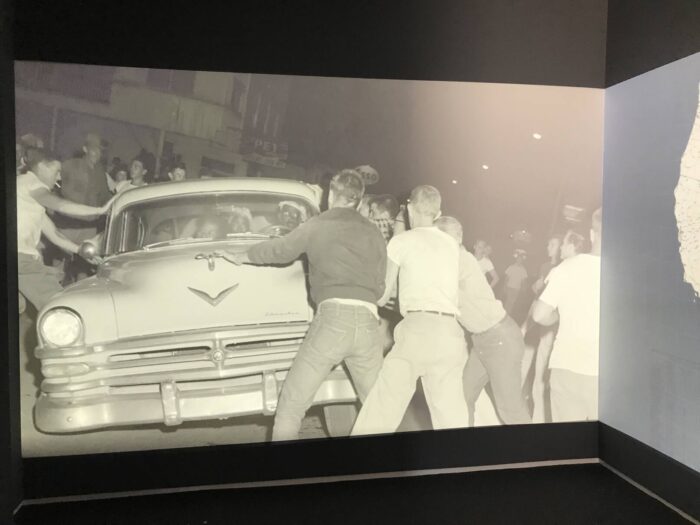

To the left of that map in the video was this image of a group of people at the top of a dominance hierarchy surrounding a few people at the bottom in a car. It looks beyond fearful for the people in the car. I don’t think it’s Jackie Robinson, but he must have known more about such possibilities than us today.

This scene reminded me of the “candy white people” story I alluded to in my post on The five times I got mugged growing up when I was in a car similarly surrounded. I was about ten years old, so didn’t know about the Jim Crow south and that I didn’t have the risk of being lynched that the people in the car pictured above did. The people surrounding the car I was in didn’t touch the car, let alone rock it as in the picture above, but, again, at ten years old, I feared for my life.

It’s taken me years—actually decades—to where I could share about that experience. The latest draft of my upcoming book covers it, but until recently, I feared backlash from people around me to share a story that conflicted with the message. The people around me included my family, Columbia University, NYU, Greenwich Village, and environmentalists, who were generally liberal and progressive and based their world view on race, as best I could tell, on white people causing racism, therefore all white people today being privileged. For me to share I lived part of my life at the bottom of a dominance hierarchy based on race (or sex or sexual preference) presented conflict with their view.

I consistently got the message that I couldn’t know what it was like, that I couldn’t experience racism, etc. They had power in my world and my parents raised me to retreat from conflict so I accepted being silenced.

As I’ve learned not simply to hide and suppress vulnerability, I no longer simply hide that as a white boy I experienced racism coming from blacks to the point of fearing for my life, then as an adult coming from liberals and progressives.

One lesson I take from the Jackie Robinson museum is to reinforce not accepting victimhood from racists. Racists don’t think they’re making the world worse; they think they’re helping the group their in. Being black, liberal, or progressive, or calling oneself antiracist doesn’t change that pattern.

The overview of his Wikipedia page:

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who was the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the color line when he started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. The Dodgers signing Robinson heralded the end of racial segregation in professional baseball, which had relegated black players to the Negro leagues since the 1880s.

Born in Cairo, Georgia, Robinson was raised in Pasadena, California. A four-sport student athlete at Pasadena Junior College and the University of California, Los Angeles, he was better known for football than he was for baseball, becoming a star with the UCLA Bruins football team. Following his college career, Robinson was drafted for service during World War II, but was court-martialed for refusing to sit at the back of a segregated Army bus, eventually being honorably discharged. Afterwards, he signed with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro leagues, where he caught the eye of Branch Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who thought he would be the perfect candidate for breaking the MLB color line.

During his 10-year MLB career, Robinson won the inaugural Rookie of the Year Award in 1947, was an All-Star for six consecutive seasons from 1949 through 1954, and won the National League (NL) Most Valuable Player Award in 1949—the first Black player so honored. Robinson played in six World Series and contributed to the Dodgers’ 1955 World Series championship. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962 in his first year of eligibility.

Robinson’s character, his use of nonviolence, and his talent challenged the traditional basis of segregation that had then marked many other aspects of American life. He influenced the culture of and contributed significantly to the civil rights movement. Robinson also was the first Black television analyst in MLB and the first Black vice president of a major American corporation, Chock full o’Nuts. In the 1960s, he helped establish the Freedom National Bank, a Black American-owned financial institution based in Harlem, New York. After his death in 1972, Robinson was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal and Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of his achievements on and off the field. In 1997, MLB retired his uniform number, 42, across all Major League teams; he was the first professional athlete in any sport to be so honored. MLB also adopted a new annual tradition, “Jackie Robinson Day“, for the first time on April 15, 2004, on which every player on every team wears the number 42.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees