Business people should understand our effect on the environment better than anyone, part 1

People don’t realize it, but business people have some of the best the skills to understand our effect on the environment. We should learn those skills from them.

I didn’t have much (any?) business experience when I co-founded my first company. I couldn’t read a balance sheet or know accounting. My science background taught me to understand general and broad patterns, which don’t suffice for running a company. Either the check clears or it doesn’t. Business school taught me how to manage cash — accounting, keeping and reading balance sheets, profits and losses, cash flows, and so on.

Many people understand how we affect our environment worse than I understood how to understand a business. In other words, they just know information but not how to make sense of it.

Accounting and balancing flows are exactly what you need to understand the environment and our effect on it. The book I talked about yesterday, Sustainable Energy — Without the Hot Air, represented how we use energy and release CO2 with graphic representations of balance sheets.

Making a balance sheet allows and forces you to compare apples to apples. The author points out countless sources measures things differently, so he puts everything in one set of units. Instead of dollars, as accounting would use, he uses kilowatt-hours per day per person. He explains what the unit means and how he came up with the numbers he uses.

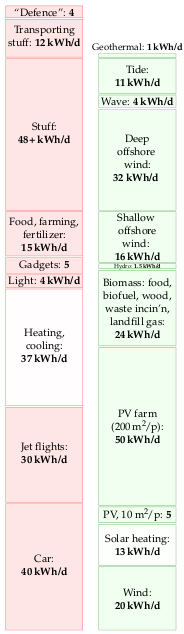

Here is a potential power balance sheet the UK could attempt (he’s British) if it wanted to exist only on renewables based on his assumptions. The left side, in red, roughly accounts for UK power use. The right side, in green, roughly accounts for renewable power the UK could generate domestically. He explains what each block means and where he gets his numbers in its own chapter.

You can see it doesn’t balance, implying the UK would need to cut consumption, import renewables, continue to rely on non-renewables, something else, or some combination. (He used loose assumptions for renewables, allowing many requiring costs I wouldn’t consider politically feasible and technological advances I wouldn’t think we could count on. So I think he overestimates the size of the right column, but I find it improves the book.)

You can see it doesn’t balance, implying the UK would need to cut consumption, import renewables, continue to rely on non-renewables, something else, or some combination. (He used loose assumptions for renewables, allowing many requiring costs I wouldn’t consider politically feasible and technological advances I wouldn’t think we could count on. So I think he overestimates the size of the right column, but I find it improves the book.)

Business people know the importance of laying out columns of numbers, accounting for them, and requiring businesses to balance columns that need to balance. If they don’t, you know the managers don’t know what they’re talking about. Though I’m sure balance sheets like the above exist in many places, I’ve never seen this representation before, nor one as effective despite its shortcomings, meaning I’ve never seen as meaningful a conversation about power use.

For example, many people talk about using solar and wind power, but I’ve never seen their potentials compared to needs — overall and relative to each other. These charts show their relative values in context.

With such a representation, as a society, we can talk effectively about shifting to renewables. Until then, we’re like a business that can’t balance its balance sheet, or even read one. Or know what one is.

We’ll bounce checks, in other words, without information organized like the above charts.

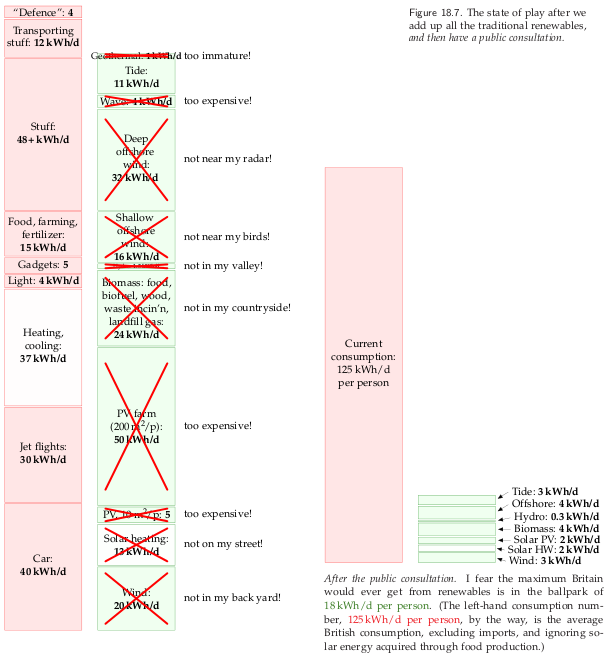

Incidentally, he modified the balance sheet based on various groups’ protests to new renewables, like people not wanting windmills nearby or visible from beaches. It implies if we don’t learn to implement and accept some new ways of doing things, we’ll have a hard time weaning ourselves from fossil fuels.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees

Pingback: Business people should understand our effect on the environment better than anyone, part 2 » Joshua Spodek