What Addiction to Polluting and Depleting Behavior Means

If I claim that we’re addicted to comfort, convenience, flying, and disposable diapers, what’s the problem if we don’t realize it? If addiction isn’t that bad and ending it seems to make life worse, why not keep flying?

Addiction leads to short-term thinking. We don’t think past the next hit when we expect one or past withdrawal if we don’t. We have trouble imagining a better life without those hits. We need it to feel normal again. We prioritize ourselves over others. We don’t notice the pain we cause people around us, or don’t care.

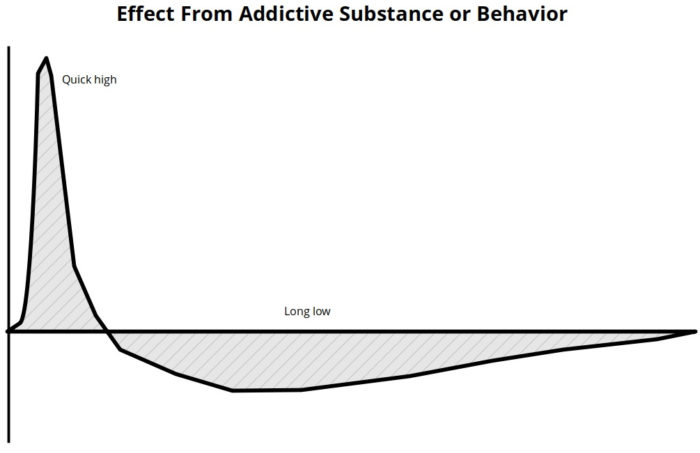

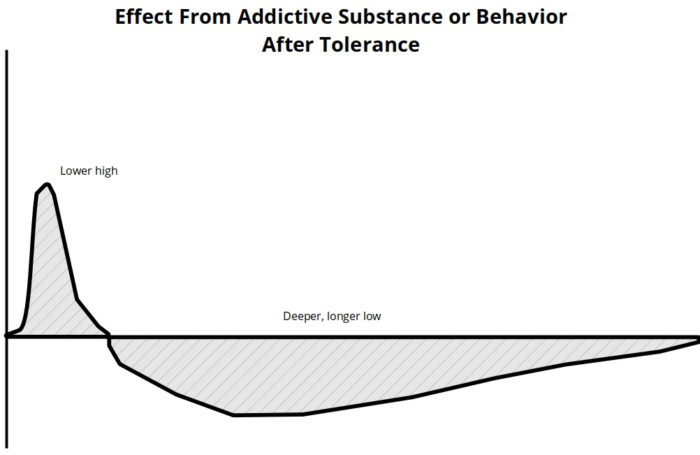

All addictions involve an intense reward that feels good. Gamblers feel like winners. Meth users feel energy. Nicotine users feel calm. Social media users feel connected. Outside that brief jolt, addiction gives you less of that feeling you get the jolt of. In other words, gamblers feel like winners despite overall losing. Meth users feel more energy for a moment but have less energy overall in life. Nicotine users feel more jittery most of life. Social media users become isolated, hence the higher rates of suicide.

Someone addicted and facing withdrawal often can’t imagine they overall experience less of their rewarding feeling. A heroin addict doesn’t see the squalor they live in. Someone who flies a lot doesn’t see that they spend less time with family, have lower financial stability, less connection with nature, and are hurting the people they think they’re helping. If you fly, that last sentence probably seems as unbelievable to you as doof addict being told that apples will taste sweeter than Ben and Jerry’s.

You tell me what you fear losing in ending your addiction and I’ll tell you what you will experience more of. Stop polluting and depleting and you will experience more connection to family, more control over your career, more nature, more adventure, more leisure, more to look forward to, more cultural exchange, more comfort, and more convenience. You will help the poor most.

Someone giving up heroin will find it hard to imagine regular life matching the predictable jolt of euphoria, but like the construction worker who gave me twenty dollars, they know it’s possible.

They’re just rationalizing and justifying their feelings of inadequacy and inability to face and overcome the withdrawal. I felt that way giving up doof and flying until the withdrawal passed. You’ll feel that way stopping doof and flying too, but deep down, you likely know you don’t need those things and that they are holding you back. No necessity of life causes addiction, only unnecessary things. Moreover, as the addicted person develops a tolerance, the high gets shallower and shorter while the low gets deeper and longer.

When I tell people about giving up an addiction, they tend to tell me what about that practice they can’t give up. If I talk about stopping using or accepting disposable cups, they tell me they don’t have time to sit and drink coffee. But the people who commit to stopping using disposable cups in favor of only drinking coffee from mugs with their spouses at home, sitting at the café, or at the office end up having more time, not less. They find themselves more productive, not less.

The more people get coffee to go, order takeout, binge watch TV, buy smart watches, and use more notifications seem more hurried but get less of value done. When you see the pattern, it’s like meth users thinking they’re full of energy, accomplishing many achievements that give a rush in the moment devoid of long-term value because addiction deprives us of long-term views and others’ perspectives. The movie Goodfellas illustrates this effect in the scene when the main character thinks the helicopter is following him. He has a busy day with many things to do, taking cocaine to energize himself. He completes task after task, feeling accomplished, yet they’re all knickknack, valueless results. He doesn’t see what’s failing: his health, safety, relationships, and so on. Our society is becoming that way.

Since we don’t realize we’re addicted, we’re like Skid Row residents cleaning up their neighborhood and replanting its trees but not stopping our addictions or our supply. We’re cleaning up our mess and planting more trees but not ending our addictions. We’re not even cleaning the mess since most of our garbage no longer biodegrades. We’re just moving our plastic and poisons to poorer people’s environments. You can’t stop the global heroin trade if you’re worried about your own supply.

When you see this pattern, you see nearly everyone worried about their own supply, including nearly all environmentalists. Have you ever heard someone addicted but in denial about their addiction talking about stopping? They don’t sound in the least genuine, saying things like the problem isn’t that bad or they could stop if it was really a problem.

Addicted people rationalize and justify until they almost believe themselves to the point of acting against their interests. They sabotage others trying to stop.

We will do anything to avoid facing our internal conflict and resulting emotions of shame, guilt, helplessness, hopelessness, and insecurity.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees

Pingback: Sustainability simplified » Joshua Spodek

Pingback: If modern technologies (flying, social media, etc) promote culture, why do they homogenize everything? » Joshua Spodek

Pingback: Wants versus Needs: How we pay for our own misery » Joshua Spodek