Non-judgmental Ethics Sunday: What if an Athlete Wants to Bet on Himself?

Continuing my series on responses to the New York Times column, The Ethicist, looking at the consequences of one’s actions instead of imposing values on them, here is a take on today’s post,â€What if an Athlete Wants to Bet on Himself?“

An athlete who bets against his team — or himself — clearly has a conflict of interest in the outcome of the game. It’s not obvious to me, however, why an athlete betting in favor of his team (or himself) would be doing anything unethical whatsoever. What am I missing? GRAHAM SINGER, CHICAGO

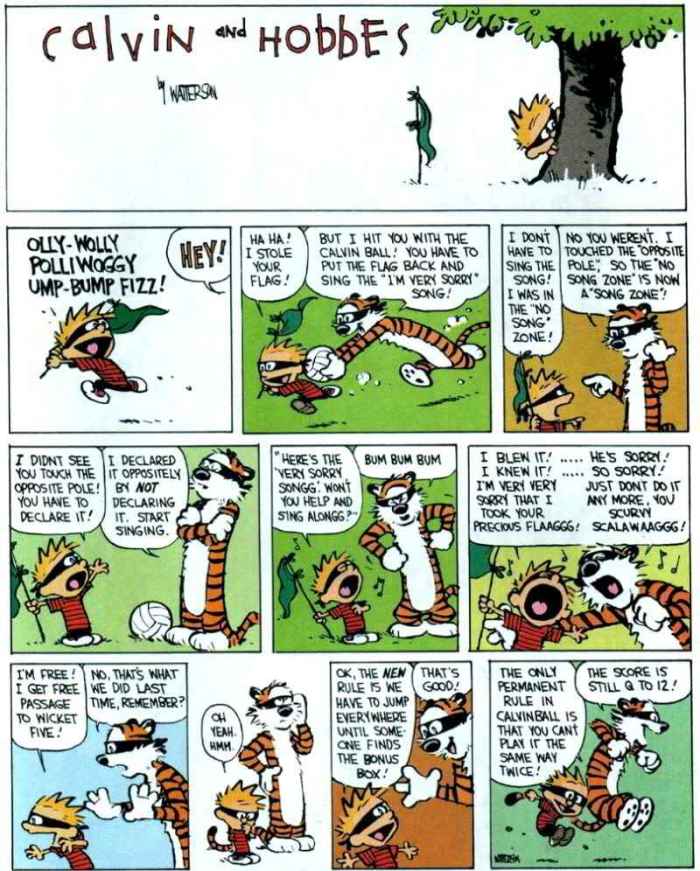

My Answer: There is a sport called Calvinball, illustrated below, with almost no rules and what rules it has change arbitrarily. It’s funny to read in a comic strip, but no league would form around it.

We base sports on rules so that you can compare different athletes’ and teams’ performances based on how they perform. When outside, unpredictable influences affect performance, we often mark it, like when the wind assist a sprinter or long-jumper, they may win the competition, but we don’t count their performance as a world record compared to someone without help from the wind.

You could say that most rules keep the competition and motivations on the field of competition, but the point of the rules is actually a red herring for a particular athlete. All that matters is that the sport has rules and if you break them, you aren’t playing that sport. Your question about ethics for the athlete is a red herring too. Basketball players foul each other all game long their entire careers. Nobody questions their ethics. They just follow the rules for what to do when a player fouls. Gambling is no different.

Here’s the rule in baseball, for example, according to this site:

BETTING ON BALL GAMES. Any player, umpire, or club official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has no duty to perform shall be declared ineligible for one year.

Any player, umpire, or club or league official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared permanently ineligible.

There’s no ethics issue beyond anyone’s opinion. The rule says the consequence to the action. There’s no ethical difference between rules on gambling and rules on anything else. Athletes are free to play other sports, but only by following the rules are they playing the sport in question.

You could ask the ethics of writing the rule in the first place, but again ethics is a red herring. You can create a sport that allows gambling and it wouldn’t be any more or less ethical than one that doesn’t. The issue is the consequences of that action. The more you allow arbitrary outside influences, the less people can compare athletes and teams, so your sport probably won’t grow.

[Hover your mouse over the image if you want to read the comic to keep it from changing]

The New York Times Answer: Ever since Pete Rose received a lifetime ban from baseball in 1989 — in large part for betting that the team he was managing, the Cincinnati Reds, would win — this issue has confused a lot of people. On the surface, it doesn’t seem wrong to wager on your own potential success, unless you somehow believe all gambling to be unethical. But there are some real problems with betting on yourself to win — they’re just less obvious and harder to explain.

To make this clear, I first need to lay out the one circumstance in which betting on yourself is acceptable: It is ethically O.K. for an athlete to bet on himself to win if he always bets on himself, always bets the same amount and does so through legal, state-sanctioned means. If all three of these criteria are met, wagering on yourself doesn’t constitute a problem. But if any one of these criteria is not met, the action is damaging to the sport as a whole.

Here’s why: If an athlete bets on himself only periodically — or even if he bets varying amounts, depending on the opponent — he is opening a window for corruption. If other gamblers know that a player who regularly bets on himself to win is suddenly not betting against a specific team (or if an athlete who usually wagers $1,000 a game has changed one particular bet to $10), he’s sending other gamblers a signal: It’s an admission by an active participant that he is not confident. The game cannot be objectively viewed as a tossup, which is necessary to any sport’s integrity. The outcome isn’t fixed, but it is compromised. The third detail, however, presents the truest threat of malfeasance. A vast majority of gambling in the United States is conducted illegally, often through organized crime. For the average gambler, this has no significant consequence. But let’s say an N.B.A. player bets huge sums on his team every night through an illegal bookmaker, and his squad suffers through a miserable losing streak. He loses more than he can afford to pay. How would a player in that position escape from this debt? What can he offer a bookie in exchange for debt relief? The answer is obvious: He can provide inside information about his own team, he can offer to shave points and he can offer to throw games. In the informal economy, an athlete who gambles poorly on himself is exceedingly vulnerable. As a consequence, so is his sport.

THE FOAMY PHONY

In line at Starbucks for my usual drip coffee, the woman in front of me ordered a pumpkin-spice latte. The clerk said, “I’m sorry, we’re out of P.S.L. at the moment.†She ordered something else. The clerk added, “Here’s a certificate for a complimentary drink the next time you come.†When it was my turn, I ordered a pumpkin- spice latte. Was this ethical? NAME WITHHELD

My Answer: Obviously you thought so since you did it. Asking anybody else their ethics is just asking their opinion. If there was an absolute measure for ethics, you’d check it for your answer. There isn’t, so all you can do is ask people their opinions. You could have just asked the clerk if they’d mind you changing your order to the same as hers to get the same treatment. Then there’d be no deception. That’s why I suggest considering consequences of actions to people—then you can talk to them and create relationships—instead of abstract concepts you ask third-party journalists about.

From my perspective, the bigger issue is what you put in your body. According to Starbucks, if you had a 16 ounce with whole milk and whipped cream, you had 420 calories, including 49 grams of sugar, 55 milligrams of cholesterol, and 10 grams of saturated fat. Even an 8 ounce with nonfat milk and no whipped cream has 24 grams of sugar.

The ingredients to the syrup they put in it are, according to this site:

Sugar, Condensed Nonfat Milk, Sweetened Condensed Nonfat Milk, Annatto (E160b, Colour), Natural and Artificial Flavours, Caramel Colour (E150D), Salt, Potassium Sorbate (E202, a preservative).

Since the first ingredient is sugar, they could more accurately call it “Sugar pumpkin spice latte.” Actually, since they don’t list pumpkin or spice, they could more accurately call it “Sugar chemical latte.”

Personally, I find that much sugar disgusting, but that’s just as much a matter of feeling as your ethics question. If you don’t find it disgusting, does my opinion make you like it less? If someone considers it ethical or not, does their opinion change yours?

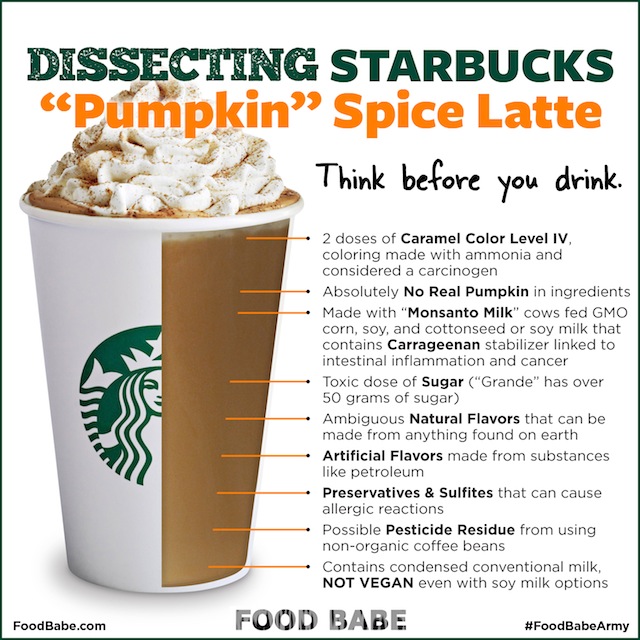

EDIT: This site researched more than the site above and found corporate spinning suggesting Starbucks wants to hide its ingredients, and summarized what they found in this image:

The New York Times Answer: No. You’re a liar and a low-rent con artist. And you live in a community where pumpkin- flavored beverages are way too popular.

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees