Where I grew up, “a national model of racial integration”: Mount Airy, Philadelphia

I found an article in the Philadelphia Encyclopedia about Mount Airy, where I grew up, “a national model of racial integration, ” created through generations of conscious, deliberate work by residents, against opposing trends the article describes below, including white realtors trying to redline and black leaders trying to protect “blackness.” My mom, dad, and stepfather participated in several institutions promoting Mount Airy’s values mentioned in the article, especially West Mount Airy Neighbors and Weavers Way co-op.

I wonder how much it caused my views to differ from the average American’s. It’s outside of my experience to grow up any place else. At my junior high school and high school, my skin color was underrepresented. How much do people assume I grew up in an environment like theirs, unlike what seems rare, nearly unique, in this country?

The article’s author: “Abigail Perkiss is an Assistant Professor of History at Kean University in Union, N.J. She is the author of Making Good Neighbors: Civil Rights, Liberalism, and Integration in Post-War Philadelphia.”

From the article, Mount Airy (West):

For more than sixty years, West Mount Airy, nestled in the northwest corner of Philadelphia, has earned a reputation as a national model of racial integration. In the years following World War II, when many American neighborhoods were experiencing rapid racial transition, homeowners in West Mount Airy worked to understand and put into practice the ideals of an integrated society. Through innovative real estate efforts, creative marketing techniques, religious activism, and institutional partnerships, residents worked to disrupt a system of separation and infuse their day-to-day lives with the experience of interracial living.

…

In 1950, West Mount Airy was home to 18,462 residents. As in urban neighborhoods throughout the northern United States, West Mount Airy residents experienced deep racial anxieties and worked hard to preserve what they saw as the integrity of their community. When black migration from the South produced a sudden influx of African American buyers, they worried that their property values would diminish, that the instability would breed volatility and crime, and that their neighborhood institutions would fall apart. Enterprising realtors quickly stepped in, spreading rumors of mass home sales and projecting intense instability and a pronounced decline in housing values.

But many residents saw the possibility of something different. Not wanting to give in to the belief that racial transition necessarily brought about neighborhood decline, white homeowners sought to find a new strategy to preserve the viability of their neighborhood: by welcoming prospective black buyers.

…

In 1953, a group of West Mount Airy homeowners, led by clergy from four area religious institutions, decided to learn all they could about local and national trends in housing and race relations. After months of research, they concluded from the evidence that a racially mixed neighborhood was both sustainable and, just maybe, even desirable. To preserve the material and cultural benefits of the neighborhood and to retain its economic viability, they decided to work to create interracial living.

At first, community leaders adopted a strategy of individual education and persuasion, including calling on residents to participate in “sell your neighborhood” campaigns and encouraging prospective buyers of “high standard” to purchase homes in the area. Through public sermons, focus groups, informal gatherings, and the creation of new community gathering spaces, these leaders promoted a positive attitude about the racial change that was occurring in the neighborhood.

…

George Schermer (1910-89), a West Mount Airy homeowner and director of the city’s Human Relations Commission, believed that the community needed an infrastructure to connect individual responsibility with broader institutional authority. In 1959, under Schermer’s leadership, West Mount Airy Neighbors (WMAN) was born as a community clearinghouse for neighborhood organizing, an institutional collaboration that became the defining principle of West Mount Airy’s organizing success through the twentieth century.

…

In the mid-1960s, local NAACP president Cecil B. Moore (1915-79) condemned both the class-based identity and the integrationist ideology of Mount Airy’s black homebuyers as dangerous to the larger African American community. Moore’s attacks touched off intense debates over the very meaning of blackness in urban space. As he tried to galvanize the black masses of North Philadelphia, the NAACP leader saw West Mount Airy as an ideological dividing line in the city’s struggle for civil rights. African Americans moving to the Northwest Philadelphia neighborhood became symbols of black middle-class complicity with the white establishment that Moore condemned. To Moore, the black middle-class residents of Mount Airy represented African Americans who had abandoned the black masses and thus given up their claims to blackness. Such rhetorical battles between the NAACP president and the city’s liberal middle-class community highlighted rising tensions within the fight for racial justice.

…

By the second decade of the twenty-first century, West Mount Airy remained one of the most economically stable and diverse areas in Philadelphia. At the time of the 2010 census, the neighborhood was roughly 41 percent African American, 54 percent white, and 5 percent Asian or Latino, with 3 percent of residents self-identifying as multiracial. Between 2005 and 2009, the median household income in West Mount Airy was nearly $85,000, almost 60 percent higher than the national median for the same period, with more than a third of residents having earned graduate degrees.

…

The area’s integration efforts allowed long-standing residents to maintain the integrity of their neighborhood by welcoming similarly situated African Americans. Together, they created a community grounded in the ideals of postwar racial liberalism, and they fought hard to maintain that ideal amid shifting economic and political pressures and evolving notions of racial justice. But the Mount Airy integration project never sought to be transformative; at its core, the neighborhood efforts were grounded in a desire to preserve their community and to retain its viability through celebrating interracial living.

My neighborhood and abolition

From another article by that author, Northwest Philadelphia, our roots go back centuries, including some of history’s earliest work on abolition. After grounding its start, “In the late seventeenth century, as William Penn (1644-1718) worked to establish his ‘green country town,’ the German Township along the Wissahickon came together as a small community”, it says:

In 1688, German Quakers published a resolution condemning the “traffick of men-Body.” In 1775, the French-born Anthony Benezet (1713-84), a longtime resident of Germantown, founded the first abolitionist society in the United States, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, later the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and by 1800, 60 free blacks (and seven slaves) were recorded as living in Germantown.

This legacy of activism persisted in parts of the region, even as it maintained an identity as a largely white and wealthy enclave.

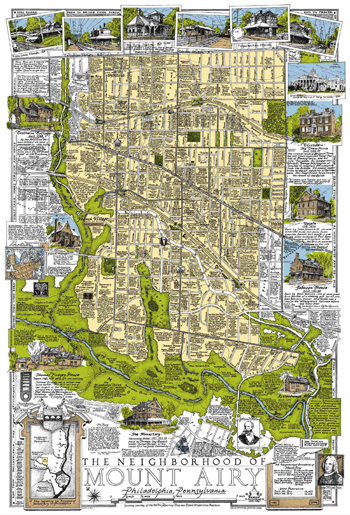

The map that prompted my finding the article

A place called the Mount Airy Learning Tree makes a hand-drawn map of the neighborhood. I bought one years ago at the co-op. Seeing it at my dad’s place prompted me looking up more about Mount Airy. Here’s a low-resolution picture of the map from their site:

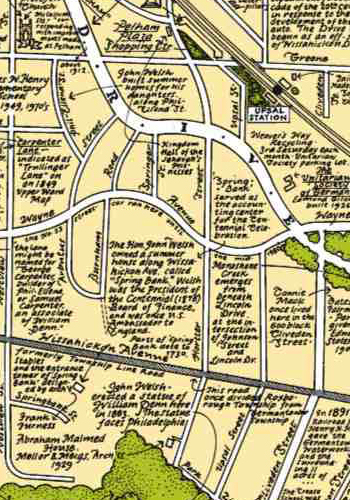

Here is a higher resolution detail from the site that happens to show near my home:

Read my weekly newsletter

On initiative, leadership, the environment, and burpees

Pingback: If you think food coops cost more or complain that some people don’t have access to them, you don’t know what you’re talking about and are exacerbating the problem. » Joshua Spodek

Pingback: The Food Coop I Grew Up With: Weaver’s Way in Mount Airy, Philadelphia » Joshua Spodek